“The most unbearable thing for a political prisoner is to fade into oblivion.” – Li Bifeng, a.k.a. LBH in For a Song and a Hundred Songs

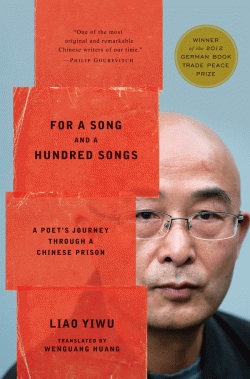

Liao Yiwu was a fledging poet without a formal education, a hot-tempered philanderer prone to fights, a dreamer who actively despised politics — until the early hours of June 4, 1989, when, from the living room of his home in the river town of Fuling, he listened with Canadian Michael Day to shortwave radio reports of Chinese troops opening fire on students around Tiananmen Square. “The bloody crackdown in Beijing was a turning point in history and also in my own life,” he writes in his prison memoir For a Song and a Hundred Songs, the book that won him the German Book Trade’s Peace Prize last October, for which an English translation was made available today by New Harvest. “For once in my life, I decided to head down a heroic path, one on which I advanced with great fear, scampering at times like a rat with no place to hide.”

His secretly recorded post-Tiananmen poem, “Massacre,” composed in the style of his beloved Beat poets, was cathartic but incomplete, only serving to stoke his revolutionary fever, which burned fiercer in part because it had been ignited so late. “Art was my protest,” he writes, and so it was that he and friends began production on a movie called Requiem. It was ultimately this project that led to his arrest in February 1990 and subsequent four-year incarceration — three months locked in an investigation center, twenty-six months in detention, eighteen months in prison. The title of his book is a reference to one of the many horrific episodes he endured, when a guard punished him for singing a song by forcing him to sing one hundred more. Unable to continue, an electric baton was inserted into his anus. “I felt like a duck whose feathers were being stripped.”

There were countless similar degradations, which Liao renders in ghastly detail. (If there are any poetic embellishments, he is much too skilled a writer to have them show.) Prison is its own hierarchical and overcrowded society, divided into classes with people filling roles, marked with cruelty, madness, and, yes, sexual assault. “As Wang Er thrust back forth violently, Big Mouth yelped in pain. Blood trickled down his thighs and the back of his knees in two distinctive lines. Inmates stood around, astonished. I sat on the edge of the bed and tears welled up in my eyes for the first time in a year.” Others are disciplined with psychological torture, manual labor, beatings; two misbehaving detainees find their hands shackled together, prompting one of the book’s funnier moments: “At the end of the bathroom break, each person would bend forward with two legs parting, waiting for the other person to reach underneath to wipe his partner’s butt. As one can imagine, mishaps occurred frequently, giving rise to bitter recriminations.” And then there is the infamous “menu” of corporeal punishment, with items such as “pig elbows braised in herbs” (“enformer jabs the inmate’s back with an elbow repeatedly until it is covered with bruises”), “saw-cut pork” (“enforcer soaks a thick rope in oil, ties it around the inmate’s calf, and pulls it back and forth until it cuts the flesh like a saw”), and “mapo tofu” (“enforcer sticks a dozen peppercorns in the inmate’s anus and stops him from pulling them out”), among many others. In this environment, Liao twice tried to kill himself — his most shameful moments, he writes, because the attempts were so futile.

Yet the book abounds with tender moments of unfailing empathy, stories of colorful characters who have done and continue to do deplorable things yet are no less human because of it. “You are right. We deserve to die. But even bad people have feelings,” a heroin smuggler on death row, Dead Chang, pleads with a guard who threatens to report he and his cohorts for protecting an inmate who has tried to commit suicide. Another death row inmate, Dead Skin, describes how and why he killed his wife, punctuating his story with this line: “I had to kill her to grow up. From now until my execution, I want to live with dignity, free from humiliation.” No one, under Liao’s observant eye and bottomless pathos, is all good or all bad. He calls Wang Er, the rapist, a friend, one who looks out for him and vice versa. After the prisoners stage a comic and somewhat tender funeral for Wang Er at his request, he and Liao have this exchange:

“I don’t believe that humans can completely turn into beasts. Don’t try to prove me wrong,” I said. “You don’t have to have the whole cell turn against you and hate you before you die.”

“But I don’t want to die. I’ve only had thirty years in this life. I wanted to stay longer in this world,” Wang Er said.

“Spending your long life in a labor camp? What’s the point?”

“I can risk my life and escape, or I can settle down and serve out my sentence,” Wang Er mused. “If they put me in jail for twenty years, I would be released at the age of fifty. I can still get a wife.”

“So, you would rather suffer twenty years to gain back an ordinary life?” I asked.

Wang Er’s face reddened with anger. “I want to live.”

And there is poetry in Liao’s stark descriptions of prison. In the detention center, “I closed my eyes and the world morphed into a colossal buzzing fly that I couldn’t chase away.” Standing before a judge, “I felt like a food particle trapped in a big empty mouth.” To illustrate the stench in the air after a constipated man finally relieves himself: “We dabbed toothpaste around our nostrils.” And to portray the ennui of a caged existence: “Like in a swarm of honeybees, each day swirled in a kind of frenetic repetition, a manic and oppressive sameness.”

The utter shame of China’s crackdown on those who participated or editorialized on the Tiananmen Square Incident, the arrests of student leaders and writers — ’89ers, as groups of them in prison are called — is that powerful, original voices such as Liao Yiwu’s will never be heard in their home country. (Liao wrote For a Song and a Hundred Songs three different times, thanks to government interference.) His status as a dissident supersedes his artistry, to no one’s benefit. Even the book jacket does Liao disservice when it claims the book “will forever change the way you view the rising superpower of China.” That’s unlikely, considering the intended audience is probably Westerners who retain an easy image of Orwellian China. What the book is capable of doing, if it could at all be viewed outside the context of dissident lit, is elevating the reputation of Chinese writers, who are oft criticized for being stale, uninspired, and unimaginative, plus all the things said about Mo Yan.

Liao burst onto the international scene with the publication of The Corpse Walker, wherein he displayed remarkable talent for recognizing that what is sharply, heartrendingly flawed about us is often what makes us most human. His latest work is deeper and fuller. It has all the stories of China’s underclass that made The Corpse Walker a success, but they are told with a stronger narrative voice unafraid to let us know more is at stake, both for the protagonist and the writer in real life. Liao references the likes of Jack Kerouac, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Marcel Proust, Milan Kundera, and, of course, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, an unsubtle attempt to place his own work within a literary tradition.

For a Song and a Hundred Songs documents how a poet’s soul descends into the body of a dissident. Liao spares no punches for himself. “How can you claim to be a poet? You are such a dick,” an officer yells at him while he masturbates. Later, a cellmate shoots him “a look of pity and disgust” after watching him kick an inmate begging him for mercy. “I deserved his reproachful look; years of living with the thieves, murderes, and rapists had transformed me.” Throughout this process, however, Liao tries to stay loyal to the truth. As an old poet and friend, Liu Shahe, advises him about his writing: “You must write honestly. That will be a perfect ending to your story. But remember to tell the truth. False testimony will be condemned by the future generation.”

Bitter and angry and vengeful as he must be, Liao only allows himself the briefest of denunciations of the Communist Party of China: “Sometimes I wonder, am I still in jail or am I a free person? It really doesn’t make any difference in the end because China remains a prison of the mind: propserity without liberty. Our entire country might as well be gluing medicine packets all day. This is our brave new world.”

He has earned the right to say that. The state has robbed him of four years of life, severed ties to his friends and family, even made his wife and daughter hate him — he has been with Miao Miao, born when he was in prison, less than two months in the last twenty years. Under threats of another arrest, Liao fled to Germany in 2011, and chances of him returning to China within his lifetime are slim. “I am my own shrink,” he writes. “I am a writer.” But is it enough? Art has been known to sustain lives, but what about happiness? “These words, which I have shared with you, the reader, form the most sincere and truthful expression of what I have seen and learned. Passing it on has given me a sense of dignity.”

On this, the anniversary of the events at Tiananmen in 1989, China could take a lesson from Liao Yiwu, if it at all understands or cares about the meaning of dignity.

Liao Yiwu’s For a Song and a Hundred Songs, released today, can be purchased on Amazon. He will speak on June 13 with Wenguang Huang, his translator, at the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building of the New York Public Library.