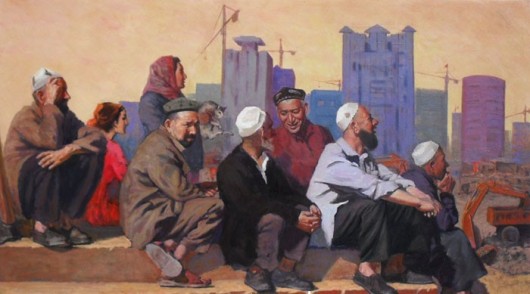

“Outlook,” by Memetjan Abla

In the wake of the horrific violence in Kunming, Uyghurs around the country have taken to Chinese-language social media to create distance between themselves and the killing of the innocent. The celebrity of Uyghur-Han ethnic friendship, the Guizhou kebab-seller-turned-philanthropist Alimjan (A-li-mu-jiang), put it best. Echoing the massively popular Indian-American film My Name is Khan, Alimjan said, “My name is Jiang and I am not a terrorist.” Many people also expressed empathy with those who experienced personal loss and pain on March 1 by writing on their WeChat accounts, “We are all Kunming people today.”

In Uyghur-language social media, Uyghurs have also condemned the attack as “ruthless and inhumane.” But in writing for Uyghur-speaking audiences, their responses include more than just outrage; their commentaries are inflected by feelings of shame, fear, and uncertainty. As one writer identified as “Tikenkush” put it, referring to the attackers, “What were they thinking? They have cast a black shadow on Uyghur people and Islam as a religion.” Since the attackers have been identified as “Xinjiang terrorists,” many fear the region, the people, and their faith will be affected as a whole.

The Uyghur Present

Based on the Uyghur-language social media networks I am a part of, many Uyghurs in Ürümchi are advising their family members to stay away from places known to have high concentrations of Han migrants such as Hualing International market (the Lowes of Central Asia). Uyghurs around the country are reporting being put on leave or having their job contracts canceled. Many hotels in major cities now refuse to rent rooms to Uyghurs.

One of the most forwarded post-“3.01” Uyghur-language Weibo messages illustrates this clearly. It described the experience of a Uyghur photographer who was in Shenyang on work assignment. In the evening he went to many hotels but could not find a place to stay. He finally went to a police station and explained his situation. After checking his ID multiple times, the police helped him get a hotel room. The next day he went to an Internet cafe, where an employee there asked him for his ID. When he showed his card, the employee said, “Your ethnic group is not allowed to go online here.” When asked why, the employee only said it was an order from “above.”

The Uyghur Future

Another writer on a Uyghur discussion forum called Gullug typified the apprehensive and self-denigrating attitudes that many Uyghurs are battling with deepening intensity. As the lines between ethnic pride and alienation are drawn in sharper distinction, this writer, identified as “David,” illustrates the ambivalence of not having a comfortable position in the nation.

Commenting first on the future prospects of being able to move and work in Chinese society, he wrote: “They have inflicted a huge wound which cannot be healed. From now on you (Uyghurs) will face all kinds of discrimination in airports and train stations, you will lose the freedom of speech and movement that you have now.”

Then turning to a discussion on quality or cultural capital (suzhi), he said: “Because of this (incident) you (Uyghurs) will be perceived as having less education relative to Tibetans and Mongols…”

Finally, voicing a strongly critical stance toward dominant Uyghur world views, the writer said: “Uyghurs are simply proud because they have a substantial population in Turkey and they are well known by Turks. They are like Ah Q1, they have no idea how statistically insignificant they are. Like the backward nationalities and tribes of the Middle East2, they will be taught a lesson. This group of bastards has harmed millions of people.”

It is interesting to note that David has to some extent internalized the civilizing discourse of mainstream Chinese society that places rural, frontier, and ethnic people in the lowest position of quality (suzhi). A long time ago W.E.B. Du Bois referred to the kind of experience David is going through as a kind of “double consciousness.” He said that the sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of the majority while at the same time trying to value one’s minority heritage puts tremendous strain on the self. David sees Uyghurs as inhabiting a position of lack. They lack suzhi, they lack self-awareness, and now “a group of bastards” has created an even greater gap between them and the rest of the nation.

1 The well-known character in Lu Xun’s short stories

2 A reference to the U.S.-instigated wars in Iraq

Beige Wind runs the website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, which attempts to recognize and create dialogue around the ways minority people create a durable existence, and, in turn, how these voices from the margins implicate all of us in simultaneously distinctive and connected ways.

Very insightful. Thanks for this.

-Billllll

Agree with commenter Bill re: the insightfulness of this post. I’ll add, from the ground here in Urumchi’s Uyghur ghetto, that security is much tighter than it’s been perhaps since late last summer. There are also lots of small visual/audio displays of power and force taking place every day, the kind that always come along with something having gone wrong here.

That post by David is something else–thanks for highlighting it. I’m curious: is there a particular reason why you chose to introduce and then use suzhi in this piece? It’s somewhat misleading, and even a little jarring to me, since 1) it’s not anywhere in David’s post (though it’s obviously related to the bit about the numbers of educated Tibetans and Mongols vis-a-vis Uyghurs), and 2) there *is* a word, sapa, that Uyghurs use to express the same concept.

Have some thoughts on some elisions in the translation, as well, but I’ll just send those to you privately if you’re interested.

Hi Insanshunas, Feedback on our translations is always welcome. The idea was to go for emotive equivalence, but we might have missed some nuances in the process.

Regarding my discussion of suzhi: the anthropologist Andrew Kipnis (2011) has demonstrated that one of (or perhaps “the”) dominant goal/s of Chinese education is obtaining suzhi (or “attained quality” as opposed to zhiliang or “ascribed quality”) in order to attain or maintain high social positions in Chinese society. In addition Emily Yeh (2013) in conversation with Yan Hairong (2008) and Ann Anagnost (2004) has demonstrated that suzhi is distributed differently based on one’s location within the nation. Developed places are places of suzhi; places at the center of Chinese knowledge production is where suzhi takes place. My sense is that David’s longing for Uyghur education is in direct relation to this discourse of suzhi.

Sapa may or may not be taking part in this conceptual discourse – I would love to know more about how you hear sapa being used. Do people say for instance “her cultural sapa is really low” when referring to someone who they view as less sophisticated? What constitutes high Uyghur cultural sapa and how is it exchanged for distinction and economic status? Would someone positioned outside the Uyghur social field but within the Chinese context recognize Uyghur sapa as suzhi?

Further Reading

Anagnost, A. (2004). The corporeal politics of quality (suzhi). Public culture,16(2), 189-208.

Kipnis, A. (2011). Governing Educational Desire: Culture, Politics and Schooling in China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Yan, H. (2008) New Masters, New Servants: Migration, Development and Women Workers in China. Duke University Press.

Yeh, E. T. (2013). Taming Tibet: landscape transformation and the gift of Chinese development. Cornell University Press.

Thanks for the thorough reply, complete with a reading list, and apologies that I’m just getting back to you. My internet situation has been worse than normal (which is never good) lately.

To address briefly your questions re: sapa: yes, indeed, I hear people use it all the time in more or less the same ways that Mandarin speakers use suzhi (and I cannot recall anyone ever having code-switched suzhi for sapa, though I’m sure it happens): “Uning mädäniyät sapasi töwän” (n.b. the second ‘a’ is long and there is no vowel reduction when adding suffixes to ‘sapa’), “uning sapasi yoq,” and the like. Offhand–without going back through transcripts and notes to look for specific instances–I think it seems to have come up most in situations in which I’ve discussed with Uyghurs 1) education in general, 2) interesting things I’ve heard/seen/experienced in the poor places of southern Xinjiang (like a 19-year-old taxi driver in Khotan who did not know what “kutupxana” meant until I told him), and 3) the general state of/problems in contemporary Uyghur society (these discussions always focus on poorness and low education levels, Uyghurs as “déhqan xälq,” and the like). It comes up quite a bit. Sapa among Uyghurs, in my understanding, is marked by a sense of cosmopolitanism, by “proper” command of “pure” Uyghur language, and by being well-versed in Uyghur literature and arts, among other things. The employees of university departments and cultural bureaus and other socially “high” workplaces are often said to have sapa (even when I personally would argue that some of them don’t!), in contrast to people who speak “kocha tili” and are in the lowest qatlam-s of society. My sense is that, yes, anyone within the “Chinese context” would likely recognize sapa as equivalent to suzhi.

To be clear, yes, I think your inclusion of ‘suzhi’ in your original post was relevant, but in your writing you could perhaps have made it more clear that the concept was part of *your* take on–rather than an original part of–David’s text.