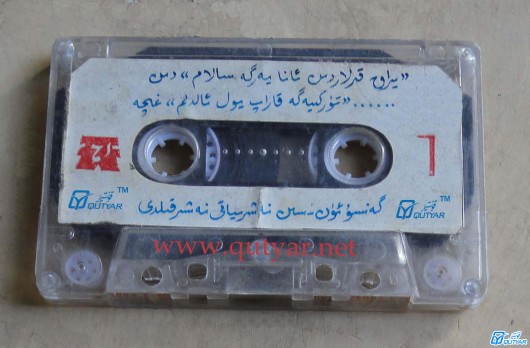

As in many Islamic societies around the world, Uyghurs listen to cassettes and MP3s of sermons, poetry, and essays as a way to tune in to the sensibilities of the rapidly changing social world and to find their place within larger communities. Those who listen to these forms of media are ordinary Uyghurs, people who work as farmers and seamstresses, small-scale traders, and handymen. They send their children to schools with red scarves tied around their necks and worry that their kids won’t be able to find their way in the new world. Many of the most popular recordings focus on ethical action, on living right, and on what the world “out there” is like. They are both entertaining and instructive. They focus on the state of things; they are full of irony and humor. They are often densely woven with the tradition of oral storytelling and other games of language and narrative. They create a soundscape that affects people.

There is perhaps no more famous a recording than the one of a long poem by Rozi Sayit called, “It is Difficult to be a Farmer.” When the recording was first released in the 1990s, the sound of rhyming sonnets filled the streets of Uyghur neighborhoods throughout Southern Xinjiang. For a time this spoken word recording was as popular as recordings of the finest folk and pop music. People remember walking down the street and hearing calls and responses as the words of Rozi Sayit echoed in sonic repetition.

The poem struck a chord because of its beauty and its recognition of common experiences in Uyghur lives. The poem amplified the position of farmers at a time when their lifeways were being devalued. It gave beauty to poverty, dignity to hard work. It gives the passion of a Sufi poet to a way of life which was cut with iron, clay, water, and aching backs.

Below are excerpts from this long poem.

It is Difficult to be a Farmer

I’m a poet because I’m not fond of lying,

I speak the truth not the lies,

My heart is filled with the flames of a fire,

The flames of that fire make me drunk,

Let me speak in this drunk state with caution:

There is nothing more difficult in this world than being a farmer.

….

He is truthful, gentle, pure and kind,

His palms never get a break from the katman.1

He says “I will work as long as ‘seven parts’2 of my body are well.

My fate is in my fields.

May God bless my hard work by giving me my daily share3 in life.”

There is nothing more difficult in this world than being a farmer.

….

He’s doesn’t have the luck of someone who holds a degree,

He never reaches the age of retirement.

He doesn’t have an “iron bowl,”4

He doesn’t have a salary or receive promotions,

He works thirty days a month, summer and winter,

There is nothing more difficult in this world than being a farmer.

….

Our hat is from the cotton that they grow,

Our food is from the grain which they thresh,

So is the meat on our plates,

Our comforter cover is made from the silk worms that they raise,

Because of his generosity we are full of life.

There is nothing more difficult in this world than being a farmer.

As Charles Hirschkind describes in his book on Egyptian cassette sermons, oral recordings of ethical messages are used to cultivate the affects and sensibilities of living properly. Although they facilitate what might be seen as a modern technique of self-discipline as part of a larger imagined community, what hooks the listeners of Rozi Sayit’s poetry is not only this impulse to improve oneself. Instead, Hirschkind’s analysis (in as much as it can be generalized to Uyghurs) would suggest that the practice of listening is tied to the phonic and poetic qualities of the language itself.

The way speakers bring forward the traditions of the past by fusing the aurality of spoken word to an analytic of the contemporary world is the way they make the past relevant in the present. It is this combining effect that invites Uyghurs to listen sensitively to what is being said. The beauty of the form, as well as the way it resists censorship as it circulates from ear to ear, is what makes Uyghurs love to listen to Rozi Sayit’s classic.

1 Katman is a kind of long hoe – the primary tool of Uyghur farmers.

2 Eyes, eyebrows, nose, ears, mouth, hands and feet.

3 Rizqe.

4 Iron rice bowl a permanent.

Beige Wind runs the website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, which attempts to recognize and create dialogue around the ways minority people create a durable existence, and, in turn, how these voices from the margins implicate all of us in simultaneously distinctive and connected ways.