This week is the screening of the seventh segment of the first round of The Voice of the Silk Road – a show that hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs watch every Friday night at 8 pm local time on Xinjiang TV Channel 9. People like the contest because they can watch their favorite performers joke around with each other; they can see people they know perform or imagine themselves performing in their place. Uyghurs see themselves trying on a performance mode popularized by mainstream English and Chinese-language versions of the show, but instead of English or Chinese pop ballads and American and (largely) Han stories of unrecognized talent, on this show they see the reverse. They largely see Uyghur folk songs, classical muqam and pop music; and they mostly hear Uyghur stories of personal triumph.

The Voice of the Silk Road is a celebration of an amateur love for Uyghur music. The contestants sing because they love to sing; they sing because they want to be famous; and they sing because they think their voice is a voice of the contemporary Silk Road.

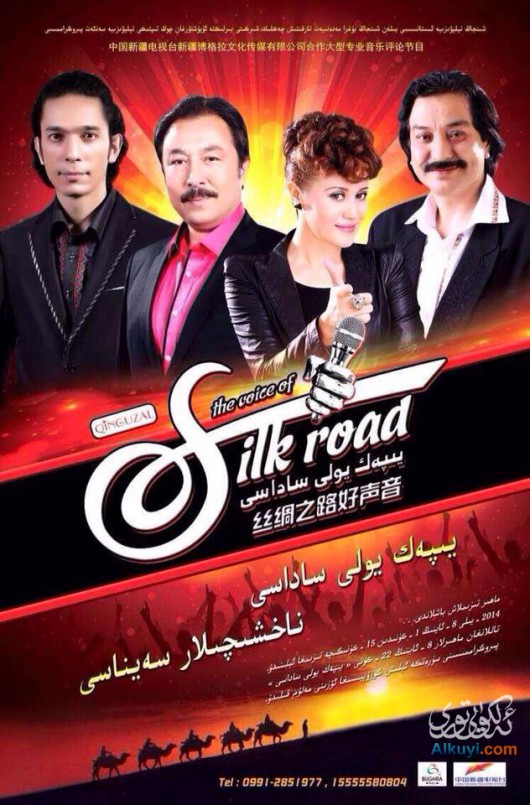

When 16 year-old Perhatjan shuffled onto the stage, everyone in the Xinjiang Arts Institute Concert Hall knew there was something special about him. The four judges — the famous flamenco player Arkin, the king of Uyghur pop Abdulla, the hyper-masculine pop rocker Mahmud Sulayman, and a little known female opera singer named Nurnisa — couldn’t see him; their tall red swivel chairs were facing the audience. Although he later said he was 16 years old, Perhatjan looked like he was about 12. Also, he was blind.

When the audience saw him being helped onto the stage, they saw that his pants were two sizes too large, and when they heard his clear, full-throttled voice, they knew immediately how to place him. He was one of those disabled kids from a poor family in the south. He was one of those singers who sings all day, every day.

He barely got through the first line of his song titled The Desire for Knowledge before everyone in the audience leapt to their feet. Nurnisa was the first to turn and join them on her feet. Erkin was the last to turn, but when he did, he too stood and applauded. As the crowd watched little Perhatjan sing his heart out, there was hardly a dry eye in the room – even Abdulla was wiping his eyes by the end of his performance. By the time he ended the song at the 4:10 mark the crowd was on its feet chanting.

The song he sang was based on a much longer lyric written by the poet Nimesehit in 1936. As a song it was first put to music by Abdurehim Heyt and then popularized by Mominjan. In Uyghur the last line of each couplet ends with the word “yoq” or “not to be.” If we translate Perhatjan’s version of the poem into English it goes roughly like this:

Among the beauties of the world, there is none as beautiful as knowledge,

A lover other than knowledge will be with you only for a short while.

If you desire becoming friends with something other than knowledge,

When hard times come there will be no one as miserable as you.

If you seek a life of ease, choose no other friend (love) than knowledge,

No other partners will be as good as knowledge in maintaining your worth.

Black eye-browed full-faced moons will accompany you for only a few days,

If you lose your money, they will leave you without shame.

Do not hope for the universe to revolve around your happiness,

Today you’re wealthy, but tomorrow you might be a beggar, or even a debtor.

In the dialogue that followed his performance the judges asked Perhatjan if he knew their songs. He said “of course, everybody does” and immediately launched into Mahmud Sulayman’s famous ode to Uyghur masculinity followed by a few lines from songs by Abdulla and Arkin.

Each of the judges tried to persuade him to choose them as a mentor. Arkin was clear in his description of who was in the room and how much everyone had enjoyed his performance. He told Perhatjan that he had worked with young singers before, and that as a young father of triplets, helping children was something very close to his heart. He and Abdulla told Perhatjan about how they would give him rides in their cars and help him overcome any problems.

It was on this point that Mahmud Sulayman asked Perhatjan directly about his family situation (a section that was curiously omitted when the performance was finally screened on Xinjiang TV). Mahmud asked him where exactly he lived and how many people were in his family. Perhatjan said he lived in the “new city” section of Kashgar and that he and his mother tried to help his father with the family business. He said that recently his mother had not been well and was no longer able to work. So mostly it was up to him to help his father as best he could.

In the end Perhatjan of course chose Abdulla to be his mentor and will compete in the following rounds under his guidance.

Perhatjan probably will not win this contest. He might make it through the next round or two but he will probably lose in the end to someone with a more mature and cultured voice. He may not win, but his voice is still echoing in the minds of thousands of listeners. The video of his performance has been viewed by more than 50,000 viewers on the Chinese Internet. His sound is the sound of what the Silk Road has become for millions of Uyghurs living in the isolated poverty of the “new cities” that are being quickly built on the stretch of the New Silk Road from Korla to Hotan.

Thanks to A. for his help with the translation of the lyric.

Beige Wind runs the website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, which attempts to recognize and create dialogue around the ways minority people create a durable existence, and, in turn, how these voices from the margins implicate all of us in simultaneously distinctive and connected ways.