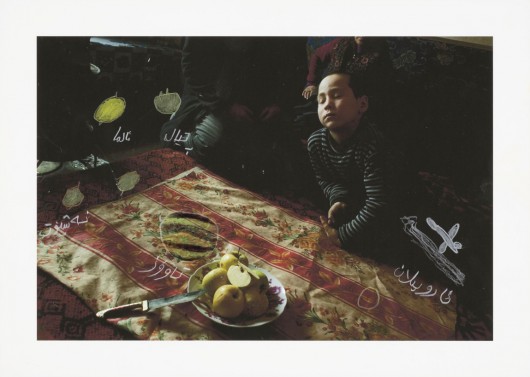

Many fantastic reviews have been written about Carolyn Drake’s new book of Xinjiang photography Wild Pigeon. Ian Johnson from the New York Review of Books commented on her innovative use of participatory sketching and collage. Photobook Bristol asked Drake how her participatory approach shaped her editorial process. Sean O’Hagan at The Guardian focused on Drake’s attempts to capture a vanishing culture on film. Colin Pantallat in Photo-eye congratulated Drake on “destroying” her images and in doing so destroying the solipsism that so often accompanies a heroic photographer. Rebecca Horne’s magnificent review at Daylight engages with Drake’s struggle to understand what her images might mean to Uyghurs. And the Time Lightbox review features lengthy image captions in which Drake relates the things Uyghurs told her as they looked at the images and realigned them with pencil and scissor. Numerous photography review journals selected it as one of the best books of 2014. Harper’s Magazine featured it as a portfolio in their January 2015 issue.

But how have Xinjiang photographers and critics received the book?

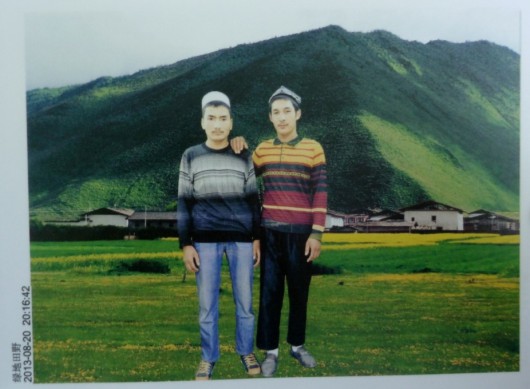

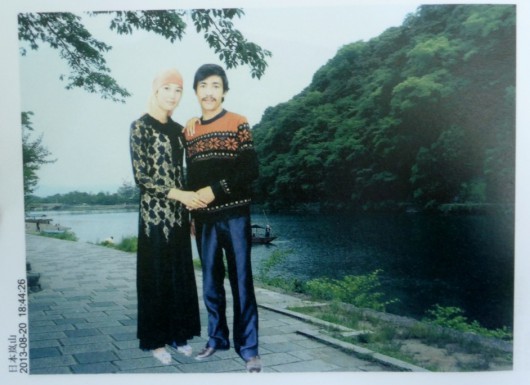

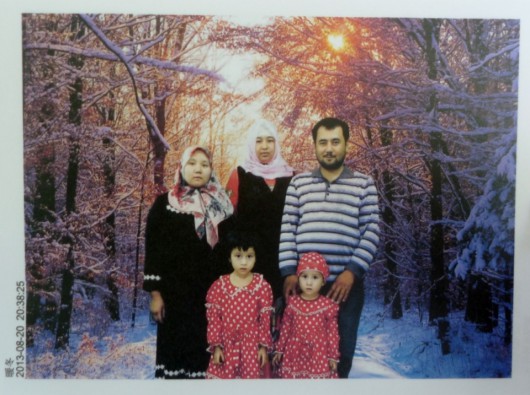

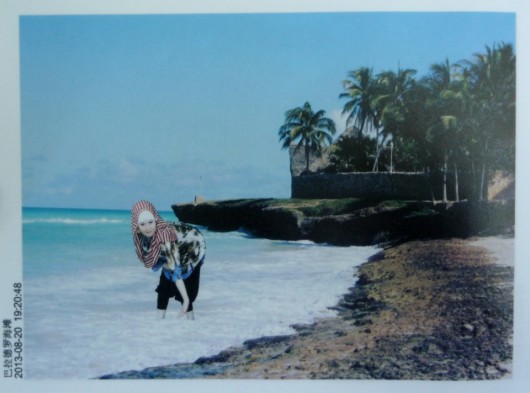

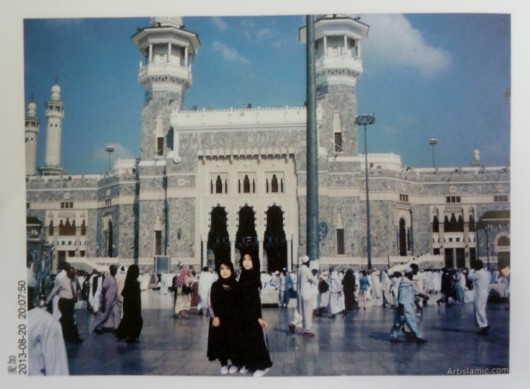

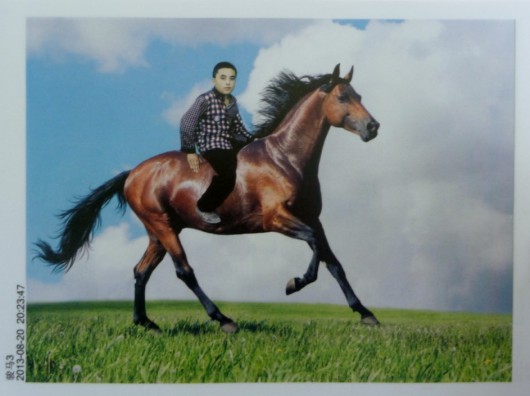

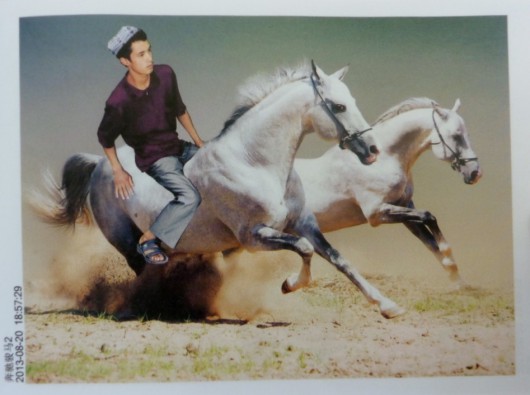

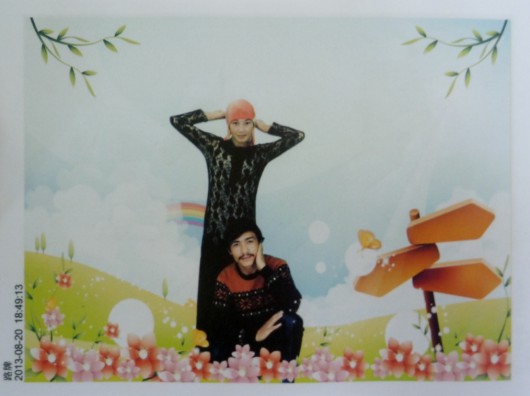

When I viewed and talked about the book with groups of Han photographers many of them noted the way Drake mixed high and low forms of art in the book. The images by Uyghur portrait photographers appended to the back cover of the book struck them as particularly interesting. The images are introduced by the words: “I see everything clearly now – the sky is still such a deep blue.” And concluded with the text: “And the world remains so beautiful and so quiet and still.”

“Why did she include these?” they asked.

Looking at the obviously Photoshopped images of rural Uyghurs inserted into exotic landscapes, they told me, “We could never do that here. If we did, people would just laugh at us. They would say, ‘You are a master photographer, and those people you are taking pictures of don’t know anything about art. Why are you acting as though their pictures are as good as your own?’”

But after we flipped through the book a few times and really looked at those pictures of Uyghurs posing in Mecca, on the beach in Varadero, Cuba, in front of Arashiyama in Kyoto, or awkwardly straddling a galloping steed, they said: “Wow, this book really is about the dreams of people. The idea is not to achieve some high standard of beauty, but to understand the desires of people.” They felt as though she had received access that would be very hard for them, as Han photographers, to gain.

Uyghur photographers were universally thrilled with the book. One told me, “These collages are really deep. I can stare at them for hours and still find new ideas and feelings in them. The colors and the way different images are positioned in relation to each other makes this a really profound and deep image.”

Even Uyghur migrants deeply identified with the images. For instance, an image of a young Uyghur man sleeping in an Internet café sparked long conversations about his own experiences as a desperado living on the streets of Ürümchi without a place to stay. He told me he had slept in a Internet café for more than 2 months back in 2011.

“I didn’t even have enough money to buy naan at that time,” he said. “I could just eat one bowl of Chinese instant noodles every day. Eventually a cousin helped me find another job as a security guard, but until I had enough money to rent a room I just stayed at the Internet café. That was one of the hardest times in my life.”

Wild Pigeon is a special book. It is of the moment and simultaneously untimely. It distills the dreams of millions of Uyghurs who live without the legal right to move beyond the borders of their home prefecture in southern Xinjiang. It shows us glimpses of these dreams; and in the strength of their numbers, the poignancy of their looks, the feelings of their words, they wear us down – wounding our hearts a thousand times.

In her commentary near the end of the book Drake mentions that the grandson of one of the old men she interviewed, a young man she knows well, is still “shuffling paperwork, stamps, and fees, hoping to obtain a passport to travel abroad. He wants to learn about what’s happening in other parts of the world beyond China. Despite the numerous obstacles, he trusts and believes he will eventually get there.”

This same dream was the dream that was hooded and shackled 109 times last week in Thailand. As those dreams are tortured, they will begin to name the family members and friends who helped them escape, and within a few weeks hundreds more will be hooded and shackled. The cycle of fear and violence will continue to unravel; pigeons will continue to flail against the iron bars of the bird cage.

Beige Wind runs the website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, which attempts to recognize and create dialogue around the ways minority people create a durable existence, and, in turn, how these voices from the margins implicate all of us in simultaneously distinctive and connected ways.