In a recent article James Leibold, a scholar at La Trobe University in Australia, discussed the way ethnic minority struggles against police and structural violence has often been officially mislabeled “terrorism.” At the same time, in China, as in the United States, violent acts carried out by non-Muslims are read as acts of the deranged and mentally ill, but not as “terrorism.” In China, as in the United States, the lives of Muslims which are lost as a result of “terrorist” or “counter-terrorism” efforts go unnoticed and unmourned. All losses of life leave gaping holes in our human social fabric, but why are some more grievable than others? What happens when a population is terrified by the discourse of terrorism?

As in many other parts of the world, the concept of “terrorism” in China was strongly influenced by Bush-era political rhetoric. Prior to 9/11, Uyghur violence was almost exclusively regarded as “splitism.” Since 9/11, as Gardner Bovingdon has shown, Han settlers in Xinjiang have become victims of “terrorism” on a regular basis, according to official state reports. By 2004, “splitist” incidents from the previous decade were relabeled as “terrorist” incidents (Bovingdon, 120). Everything — from the theft of sheep to a land seizure protest to a fight with knives — can now be labeled as “terrorism,” as long as Uyghurs and Han are involved in the conflict. It appears as though “terrorism” (or the “three forces” continuum – separatism, extremism, terrorism, which are now understood as manifestations of the same phenomenon) has come to signify Uyghurs who are verbally and physically un-submissive or “unopen.” That is why a moderate intellectual like Ilham Tohti can receive a life sentence on the charge of “separatism.”

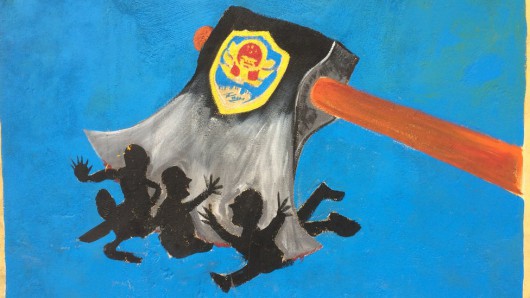

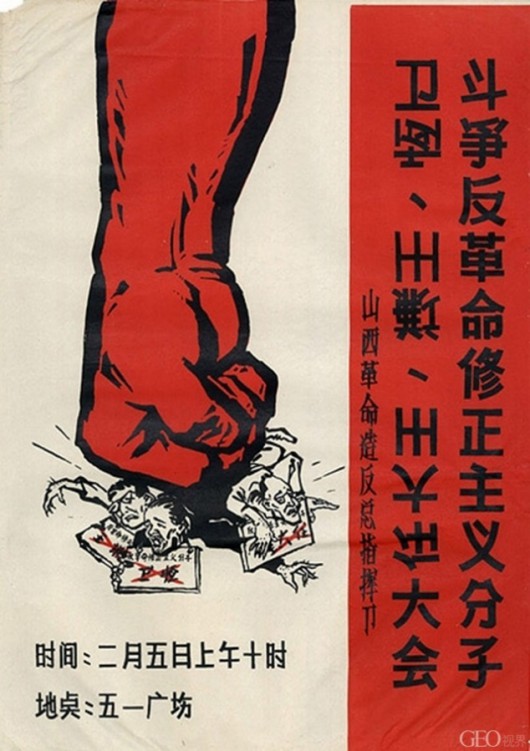

Clearly the American discourse of a “Global War on Terror” has set the terms of “The People’s War on Terror” in China. But it’s been deployed with more sweeping intensity in China, particularly in Xinjiang. Over the past couple of years, Uyghurs in Southern Xinjiang have told me that what they are facing now is much worse for them than the Maoist Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 70s. They told me that Uyghurs can be accused of “terrorist” sympathies, and once under “enhanced interrogation techniques” in detention — to borrow a Rumsfeldian turn of phrase — they often turn on their own neighbors and friends, offering them up as the “real terrorists,” etc. The way neighbors and family members have been pitted against each other through this process reminds them of the way students turned on their teachers and parents during the Cultural Revolution.

Making matters worse, real terrorism — if we define it as premeditated killing of civilians — indeed exists, as evidenced by the incidents in Tiananmen, Kunming, the Ürümchi train station, and Ürümchi green market over the past few years. These horrific acts of violence are unjustified under any circumstance and must be condemned. Yet we forget that hundreds of unarmed Uyghurs have been killed in protests, shot on the spot for arguing or fleeing, and thousands have been indefinitely disappeared following violent incidents.

As the anthropologist Talal Asad has noted in his book On Suicide Bombing, “The discourse of terror enables a redefinition of the space of violence in which bold intervention and rearrangement of everyday relations can take place and be governed in relation to terror” (28). The label “terrorism” has not only been used as a tool around the world to delegitimize instances of resistance that might be better understood as anti-colonial struggles, but it also allows for a sharp intensification of policing or “hard strike campaigns” among marginalized populations. As the theorist Michael Walzer has noted regarding the “peculiar evil of terrorism,” it is “not only the killing of innocent people but also the intrusion of fear into everyday life, the violation of private purposes, the insecurity of public spaces, the endless coerciveness of precaution” (in Asad, 16). The state of emergency that “terrorism” produces is especially acute among populations which have been identified as the source of “terrorism.” In this framework the anxiety that infects Uyghur lives, governed by the fear of being labeled “a terrorist,” is an example of how cruelty, rather than an ethics of care, has come to govern the world. Asad writes:

It seems to me that there is no moral difference between the horror inflicted by state armies (especially if those armies belong to powerful states that are unaccountable to international law) and the horror inflicted by its insurgents. In the case of powerful states, the cruelty is not random but part of an attempt to discipline unruly populations. Today, cruelty is an indispensable technique for maintaining a particular kind of international order, an order in which the lives of some peoples are less valuable than the lives of others and therefore their deaths less disturbing. (94)

Thinking about “terrorism,” and how it terrifies groups of people, thus opens up questions about whose lives matter. If Uyghurs are now “terrorists” until proven otherwise, when is the loss of a Uyghur life grievable?

Beige Wind runs the website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, which attempts to recognize and create dialogue around the ways minority people create a durable existence, and, in turn, how these voices from the margins implicate all of us in simultaneously distinctive and connected ways.