A Photo Booth creation: instead of art school, just pull out your Mac to save yourself time and money.

While huffing bubbles into my coconut’s milky core, I told my Beijing-born friend nonchalantly and without embarrassment that I had graduated from art school with a major in painting. Her response? “Great! Well, at least you can sell your paintings!” My nasal passages flooded with fruit juice. This was a far cry from the more common American response, “So you get to eat, like, what, once a week?”

Chinese students go to art school to make money. Seriously. And art school is rapidly becoming a sexy alternative for those whose math and other academic skills don’t live up to the country’s stringent testing standards. But as you’ll see, art schools here have their own rigid assessment system that’s hardly better than requiring students to memorize a database of testable facts.

The main path, if not the only path, into a top art school is through the art gaokao (college entrance exam) that judges technical skill alone. For high school students who don’t have the background, there are cram schools where students can spend nine or more consecutive hours a day drawing in a photo-realistic style not far off from the crosshatch effect in Photo Booth. (Note to cram school principals: the reason Photo Booth exists is so humans don’t have to waste their time.) There are advantages to this kind of process – good hand-eye training will never lead one astray, and there’s no question drawing helps one learn to see the world – but it’s dubious that it will foster creative thinking, which is what Chinese art generally lacks.

By contrast, sometimes all it takes to get into an American art school is the ability to support your aesthetic decisions with plausible arguments.

Question: Why did you put a puppy in your painting?

Answer: Because I like puppies.

REJECTED

Question: Why did you put a puppy in your painting?

Answer: Because it symbolizes contemporary art critics’ unwillingness to take responsibility for their positions and call out bad art when they see it.

ACCEPTED

One of the Rhode Island School of Design’s infamous application questions is simply, “Draw a bicycle.” Cleverness is rewarded. A perfectly rendered pink fixed-gear in the middle of a white page may not cut it. But a bikeless hutong as commentary on the endemic of bike thievery? It’d muscle out the competition. I probably shouldn’t need to say this, but in China’s art system, it’s the fixed-gear bike that’s encouraged, with a craftsman’s exactitude in spacing between the spokes. Technically skilled? Yes. Creative? Not really. (There are art students at the Central Fine Arts Academy [CAFA] in Beijing who also keep a studio off-campus for their more outrageous art-making, but that doesn’t seem to be the norm.)

Once you get into a top Chinese art school, whether or not you become an artist in your own right is neither here nor there. There are jobs to be had in design, fashion, etc. And there’s always a contingent of students plucked straight out of art school by collectors hoping to make a killing by discovering the next Yue Minjun. The same thing also happens in the US, though I hope most art students there are realistic enough to realize that expendable income is scarce at the moment. Here in China, with the market still booming and students able to put up a “show of their very own” in any old abandoned space, the dream is still alive. I just don’t want to be the one to tell them that in a few short years, art schools will become oversaturated, collectors will be wiser, and the competition will be cutthroat. And then it’ll be those creative wunderkinds who can create dreamscapes for the real world who will be rewarded.

Artist of the Week

Which brings us to our CAFA representative of the week: Xu Bing (b. 1955, contemporary artist and professor at CAFA).

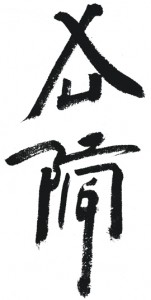

Out of a long career of nonpareil brilliance came Book of Heaven, consisting of hundreds of books laid out in a rectangle underneath a draped 50-foot scroll. All of these surfaces are covered in “characters” – thousands of characters, in fact, none of which can be found in a Chinese dictionary. They are all made up of existing radicals and character pieces that when fitted together mean absolutely nothing. The common foreigner and the Chinese intellectual alike are faced with a gibberish-encrusted celestial scroll. (Though you’re supposed to be able to read the word to the right regardless of Mandarin ability.) Along with several other artists self-defined as making “anti-writing” art, Xu forces us to admire his work from a purely aesthetic level.

As a bonus, as a life preserver to my fellow struggling artists (or struggling anythings), read this letter from a young American artist fighting to survive in the New York art jungle (cue mall scene from Mean Girls) addressed to Xu Bing. The situation is comical: a student soliciting the most famous contemporary Chinese artists for help. Then read the Master’s response. This exchange perfectly embodies all of the insecurities that artists always had and always will have.

Ask an Artist

Got a question about art? Send to lola@beijingcream.com. This week’s question:

“Why is it that artists all have a shtick? Does it occur organically, or is there cynical manipulation involved on the artist’s part?”

-Perplexed in Peking

Dear Perplexed,

All artists have a shtick because we have to sell work somehow, and more often than not it’s the same way that Victoria’s Secret sells “work.” (Breasts. And since men don’t have them, they paint them.) Rarely is image creation organic, especially in the age of Facebook. For the same reasons that social media can break a politician, it can make an artist. Everyone loves a scandal.

For no particular reason, we’ll start with Millie Brown literally puking up rainbow goo, following in a disgusting tradition of artists exhibiting bodily secretions.

Andy Warhol pissed on a bunch of canvasses – as did lots of others.

Chris Ofili made a Madonna out of elephant dung, and the shtick made him.

Vito Acconci, in Seedbed, skulked under a ramp and jerked off for eight hours a day for two weeks while gallery patrons walked above him listening to his obscene sexual imaginings being broadcast over loudspeakers.

This man painted his naked daughter over and over and over. (One wonders: is the mother’s admitted jealousy just a carefully calculated market scheme to add to the image of a fucked-up family? It got publicity, so I guess it worked.)

Hitler painted? There’s a shtick if I ever heard one.

And winning the award for longest-running shtick of all: “Spiritual Child Prodigy” Akiane. Of her patron she says, “I just like him… he’s taking care of me like I was a little butterfly.”

All of the above goes to show that if you sell it right, they will buy.

But I’m sure if I ever came face to face with Millie Brown’s goo, I would do the same thing I (and a whole bunch of others) did to Warhol’s whiz cadre: sniff it. And that would be the full extent of my interest. Even if we allow for the illimitable and generous definition of art being “anything,” as a society it’s important to acknowledge that goo art isn’t good art. It’s not good anything.

Lola B is an artist in Beijing. She can be reached at lola@beijingcream.com. |Yishus Archives|

Pretty nice post. I just stumbled upon your blog and wanted to mention that I’ve really loved surfing around your blog posts. After all I will be subscribing on your feed and I’m hoping you write again very soon!

The fake character with real radicals that you are supposed to be able to read is the Artist’s name. Just in case anyone missed it. I wanna take credit for seeing it before anyone else does because I feel special. I’m one of those guys who can never see the fucking sail boat in the 3D pictures where you’re supposed to relax your eyes, so this is kinda big. Somebody praise me. Haha.

You’re out to set some kind of commenting record, aren’t you? *virtual pat on back*