Via Learn to Art

Asked why she painted the mausoleum yellow – “This is wrong,” the Chinese art professor scolded – the foreign student at a top Chinese art school provided a thorough rejoinder defending the logic behind her aesthetic choice. The girl’s translator relayed the information to the professor. The next second, the student found herself kicked out of class for insubordination.

I bet in any Western art school, not having an explanation would be considered the insubordinate act. The value of American arts schools – the reason that their tuition can be so high – lies in the value of the critique. How is it done? In the standard art school, a student puts one or more pieces in front of the class. In proper firing-squad procession, classmates shoot holes in the artist’s crazy (and probably alcohol-induced) rationale.

The point of this exercise is to help the artist-in-training make better work. The need for a thoughtful answer is paramount, and yes, bullshitting is permitted. The point is to understand that you, as an artist, are making a statement with your art, and you need to be responsible for what it says. A critique is the interaction between art, the artist, and the audience. We pull the artwork apart piece by piece to reveal more and more, and it’s exciting. Sometimes the critiques are constructive, and sometimes you’re told that emptiness could better fill nine square feet of wall space. Oh, and I had an art teacher threaten to hang students for making bad art… but at least he allowed us our due rebuttals.

The Western critique system is the foundation of Western art. Without it, there would be no critics. And surprise, surprise, what do we think is lacking in the Chinese art world? Critics.

In China, when a teacher enters a classroom and approaches a work-in-progress, the student will say reverently, “I’ve been looking at the swirls of Van Gogh.” The teacher might say, “You might want to look at Seurat’s spots,” add a little spiel, and then the kid will go, “Okay,” and keep chugging along.

This idea that the professor is always right is a chimera of a concept in the US: mythical and/or unknown and/or to be slain upon sight. Of course, the American system might deny a professor’s ability to pass a judgment a bit too frequently, but the US has art teachers who ask questions, students who give answers and ask new questions, and teachers who then ask even more questions.

Chinese art could do with a little more healthy discussion. You hear that, people out there? This post has a comments section…

Artist of the Week

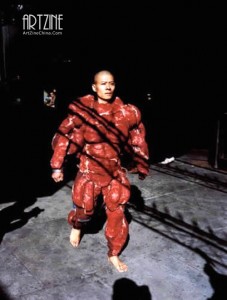

Zhang Huan (张洹, b.1965) is a Chinese artist primarily based outside China (for reasons related to government officials). Most of us probably know him from photo stills of his performance pieces. It’s not every day you see a man covered in meat (My New York, right)… though apparently it’s not that uncommon either. In one of the works that made Chinese officials a little uncomfortable, he painted himself in honey and fish oil and sat in an outhouse, letting the flies accumulate all over his body. This was seen as a commentary of the state of living in China. Most of the work he makes uses the body as a platform for exploration, and often involves the self-infliction of pain. Other works include larger-than-life statues made of incense stick ash gathered in Shanghai temples, kinetic statues of a well-endowed donkey noisily humping the Jin Mao tower, and a bronze Buddhist-style bell with the names of eight generations of his family carved into it next to a horizontal life-size metal cast of his own body. The bell is rung when the head of his metal self-portrait is rammed into the bell’s solid side.

Zhang Huan (张洹, b.1965) is a Chinese artist primarily based outside China (for reasons related to government officials). Most of us probably know him from photo stills of his performance pieces. It’s not every day you see a man covered in meat (My New York, right)… though apparently it’s not that uncommon either. In one of the works that made Chinese officials a little uncomfortable, he painted himself in honey and fish oil and sat in an outhouse, letting the flies accumulate all over his body. This was seen as a commentary of the state of living in China. Most of the work he makes uses the body as a platform for exploration, and often involves the self-infliction of pain. Other works include larger-than-life statues made of incense stick ash gathered in Shanghai temples, kinetic statues of a well-endowed donkey noisily humping the Jin Mao tower, and a bronze Buddhist-style bell with the names of eight generations of his family carved into it next to a horizontal life-size metal cast of his own body. The bell is rung when the head of his metal self-portrait is rammed into the bell’s solid side.

One of my all-time favorites will always be his Beijing performance from 1995, To Add One Meter to an Anonymous Mountain, which led to an even better piece made a decade later by Zuoxiao Zuozhou, a participant in Zhang’s original performance:

This short video is worth watching, and will give you a good sense of Zhang Huan and his work. One netizen said of him, “Bruce Lee of Performance and Visual_ Arts is ZHANG HUAN~”. Thank you, antbryant1, for your insight.

Ask an Artist

Got a question about art? Send to lola@beijingcream.com. This week:

“If you painted elements of the candle flame in such a way that a photograph couldn’t capture it, would it be worth more?”

- Alicia

First, let’s define the word “worth.” Do you mean monetarily? Or “spiritually”? Since the WSJ article in which the painting to the left appears describes the artist Gerhard Richter as “the top-selling living artist,” I will assume you mean the former.

But first, let’s talk a little about candles. Candles have been in art ever since there were candles. Check out Robert Campin’s 15th century Merode Altarpiece. A candle with a flame can represent time (especially if the candle is melted down), or Jesus (because the wax that comes from virginal bees has at its core the wick representing his soul). A candle that is blown out often represents mortality, death, or loss of virginity. One might note that in the case of the Merode Altarpiece, the candle has been blown out. There are two suggestions for its meaning (normally in Annunciations the candle is lit). One option is that the light of Jesus’s implantation in Mary’s belly is so bright that all material light is now pitifully small. The other idea is that the figurative light of Jesus has now been made physical in Mary’s womb. If you want to read more about the Merode Altarpiece, go here. What does Richter mean by his candle? Probably a mixture of all of the above, but what is certain is that his candle is more than a nod of the head to the old Dutch Masters.

Anyway, back to the point…

Why photorealism? Well, in this case, it’s Richter’s shtick — the reason the candle is expensive is because it has Mister Richter’s name on the price tag. If he had painted it differently, it would probably cost nearly the same amount. By the way, I do like his paintings, and I would pay money for them.

If it were random candle art, then style would factor into the price. So it comes down to demand. Who’s buying candle art? Some people buy candle art because of its Christian symbolism. Some people buy candle art because of its not-so Christian symbolism. Some buy it because it’s Elton John’s Marilyn Monroe. And some people just put candles in performance art. I don’t think I’d allow open flames in my museum, personally speaking.

I can tell you that in China, as long as the painting – any painting – is done in a photo-realistic style, it will probably fetch a pretty good price. Just because it looks like a photo doesn’t make it good. Just because you are in awe of a painter for being able to essentially “copy and paste” manually and in thin, slippery oils doesn’t mean you should buy it. But, I suppose, if there are willing buyers, there are a lot of people richer and a lot sillier than I am.

Lola B is an artist in Beijing. She can be reached at lola@beijingcream.com. |Yishus Archives|