I leaned over my Japanese eel handroll bought by the 10-year-old Chinese girl’s mother who was decked in glistening gold chains and a sparkling chemise. Looking squarely at the girl on this, our very first appointment, I asked her, “What is bad art?” She matter-of-factly responded, “Art made by grown-ups.”

As an interim project to help keep a trickle of income, I had agreed to take on an oil painting student. Even at our first meeting, it was clear that my pupil was one of the most visually oriented people I had ever met. If she could think it, she could draw it. If she couldn’t find the words, it would come out in highly precise line drawings. A perfect creative friendship ensued.

I taught her drawing and painting once a week. With the luxury of only having one student, I was able to handcraft lesson plans that I felt would hone her sense of art theory as much as her motor skills. When we first started our classes, she was in the middle of applying to a famous Chinese arts middle school in Beijing. She was excited to have more time for formal art training, and her parents completely supported her future goal of becoming an artist. I was in fact instructed to teach their child a more Western approach to painting.

So we had lessons in composition, color, lighting, texture… She was my canvas, and I could give her everything she needed to get into any of the best American art schools. She was eager to learn, and had a fantastic memory. Layers of art lessons started to pay off as I taught her to frame her subjects from more interesting and surprising angles. She learned to push this foreign concept of oil paint around a primed piece of paper. She began to adopt the idea of paying attention to the entire image plane all through the creative process rather than focusing on one square-centimeter of detail at a time. Cue Eliot’s fanatical scream of, “It’s working, it’s working!” when he successfully calls E.T.’s parents to end their alien playdate.

Then the new school year commenced at her new arts middle school. All the lessons I’d drummed in began to slip away. Before drawing anything, she would sketch out an elaborate system of perspective lines the likes of which I’d never even seen before. I would tell her to draw a cup in one minute — she would need 30 just to get the outline done. Once the outline was set, it would take another 10 minutes of particular erasing to remove the drawn perspective scaffolding. Was the cup realistic? Definitely. Was it interesting? Not in the least. And let me make it clear that a cup can be interesting. So, knowing that the school had them learning to paint simple objects, and wanting to break free of the thickening psychological bondage, I instructed her to paint her aunt, who would sit in the corner of our studio and wait for her. The girl’s response? “I haven’t been taught to paint people.”

Oh, I know, I know, but I had her where I wanted her, and I wasn’t about to back down. I set up the easel, the paints, everything. I knew she was more than capable of drawing things she’d never even seen before. Her hand-eye coordination guaranteed a victorious aesthetic outcome. I was ready for the magic. But then… nothing. A mental block had been erected. She repeated the same phrase. I tried to give pointers, but nothing helped. We ended up with a Motherwellesque blob to beat all blobs.

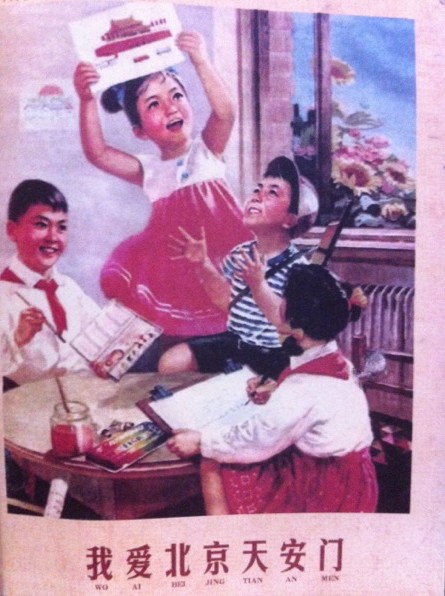

We all know that children are more creative than adults. Very much in agreement with my charge, Picasso once said, “It took me four years to paint like Raphael, and a lifetime to paint like a child.” So what was happening to my student? Was she just growing up? Or, more likely, was the system starting to strangle her?

I don’t agree with the insinuation that China itself isn’t creative. I think there’s a lot of creativity to be had, but what is the problem in this case? Over-training. My little artist was being taught tools as rules. Realism does not make up for lack of concept.

Art study in the US is rather anemic when it comes to the formal training of draftsmanship. Perspective and figure drawing are taught, but not very well. Students are taught to draw 1-point and 2-point perspective, but they are often by people who don’t understand the concepts themselves. But these visual systems should not be put above imaginative exploration as much as they are in China, either. All one has to do is look at the annual Chinese Realist Painting Exhibitions at The National Art Museum of China in Beijing to see that obsessive-compulsive perfection of craft does not necessarily make art. I don’t care if you can paint the most accurate pile of books. Nor do I care if you paint perfect naked girls. A naked girl does not mean your scribbling is Art with a capital “A.”

Art education is not perfect in China or the US. Let’s work on taking the best of both worlds.

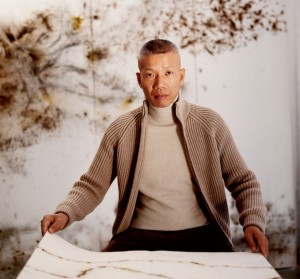

Artist of the Week

Born in Quanzhou City, Fujian province, Cai Guo-qiang (蔡国强, b.1957) has pieces on display in collections all around the world. Most recently, his “Mystery Circle” exploded on Saturday, April 7 at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles — literally. A Chinese artist with a cultural predilection for pyrotechnics, Cai used gunpowder and stencils to create large “drawings.” Amusingly enough, there were reports of duck-and-coverers at the performance. Obviously these noobs have never lived through Spring Festival in China.

Although slow motion maybe should have been avoided, this video does a good job of laying a foundation of understanding for his current fireworks. Good art can be hard to find, and I’m sorry that this particular piece was not accessible to those of us here in Beijing.

Although slow motion maybe should have been avoided, this video does a good job of laying a foundation of understanding for his current fireworks. Good art can be hard to find, and I’m sorry that this particular piece was not accessible to those of us here in Beijing.

Cai Guo-qiang’s work doesn’t even need to be physically explosive to create a stir. In his “Inopportune: Stage Two, 2004,” shown at New York’s Guggenheim Museum in 2008, nine lifelike replica tigers, skewered like St. Sebastian and suspended throughout the gallery, protested animal cruelty. Or if you like cars suspended in museums, click here.

Cai employs a small army of assistants to support him in the making of these large-scale works, so if you happen to be in a city near this artist, I suggest you email him and apply to help out.

Ask an Artist

Got a question about art? Send to lola@beijingcream.com. This week:

“What’s with all the damn plastic prefab-looking statues? Doesn’t anyone do stone anymore? Why do all these pieces of ‘art’ look like f’n toys? I can order plastic toys from a factory, too. What happened when the computer wasn’t helping you do this shit? What happened to all the love? This just seems like a cop-out. If I see a 12-meter pile of shit sculpture, I’d like it to actually be sculpted.”

– Severely Concerned in 798

Dear Severely Concerned,

A lot of materials that are highly regulated in the West for being unhealthy are not as regulated here. Making fiberglass in China is quick and cheap. Often, large, cartoony, and brightly-colored fiberglass works come off as kitschy, although once in a while, they are absolutely brilliant.

Whether good or bad, most of the time, if one can use other materials, I strongly suggest it.

If you need sculptures to look at:

- Look up Ron Mueck, whose terrifyingly lifelike figurative silicone sculptures toy with scale to mimic the psychological state of mind.

- See Ai Weiwei’s earlier works involving rampant and rule-defying furniture.

- See British Andy Goldsworthy’s artistic process as he builds entirely natural site-specific works in the 2001 movie Rivers and Tides.

- Or there is always Jim Reinders’s 1987 “Carhenge” — vintage automobile replica of Stonehenge — in western Nebraska.

- Or if you want actual shit art, made of more comprehensive materials, here’s a fecal Venus de Milo.

Lola B is an artist in Beijing. She can be reached at lola@beijingcream.com. |Yishus Archives|