In Foreign Policy’s introduction to its latest slideshow of rare photos from Tibet during the Cultural Revolution, the line that jumps out to me is the last one: “This installment of FP’s Once Upon a Time series shows the Land of Snows from a long-forgotten period, when Tibet’s enemy wasn’t China, but itself.”

The line, I’m sure, was born out of evidence suggesting Tibetans were not mere victims to the Chinese destruction of their country. This is true in one sense: Tibetans participated in the Cultural Revolution. They participated, and continue to participate, in the very institutional bases of the revolution: the school systems, the police force, the government offices, and so forth. Melvyn Goldstein, in On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2009; chapter one is available here), quotes a Tibetan who says:

[I]n August 1966 the Red Guards were everywhere in the whole country, and Lhasa didn’t want to be left behind. Therefore we formed our own Red Guard organizations…. Most of the students in my school were Tibetans. It was a concern that the Tibetan students might get into trouble, for they didn’t know the right [ideological] direction. Therefore, the Party Branch at the Lhasa Middle School decided to select a few young teachers to join the Red Guards, working as leaders. I remember I used to lead students to “destroy the four olds.”

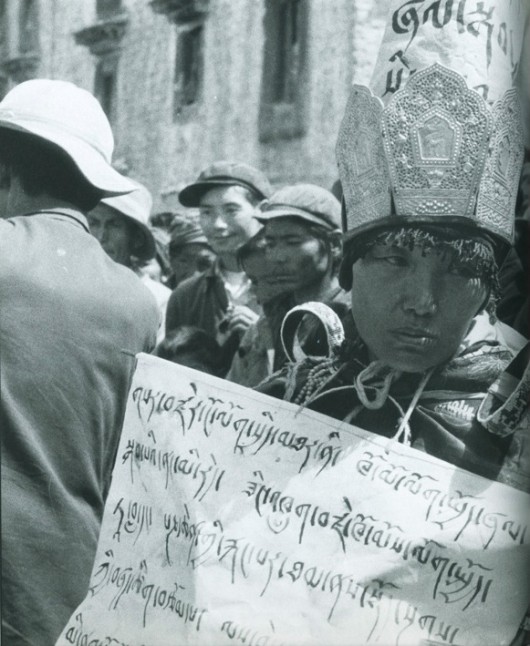

But rather than making the distinction between an enemy within and one without, I think it’s more useful to consider the period from a ground-level, Tibetan perspective. Writer Tsering Woeser (the FP photos are from her father) offers a glimpse.

The Chinese title of her book is Killing and Plunder (杀劫). The pronunciation of this title, sha jie, is a homophone with the Tibetan word for revolution (གསར་བརྗེ་), pronounced sar jé. She adds that the Tibetan word for culture (རིག་གནས་), pronounced rik né, is somewhat homophonous with the Chinese word for humanity (人类), pronounced ren lei. (See this Danwei article.) So what was the Great Cultural Revolution in Tibet? It was the Great Killing and Plundering of Humanity. It was a tragedy – an orgy of violence and pain – just as it was in the rest of China, but particularly painful due to Tibet’s exceptionally strong connection with its culture and history.

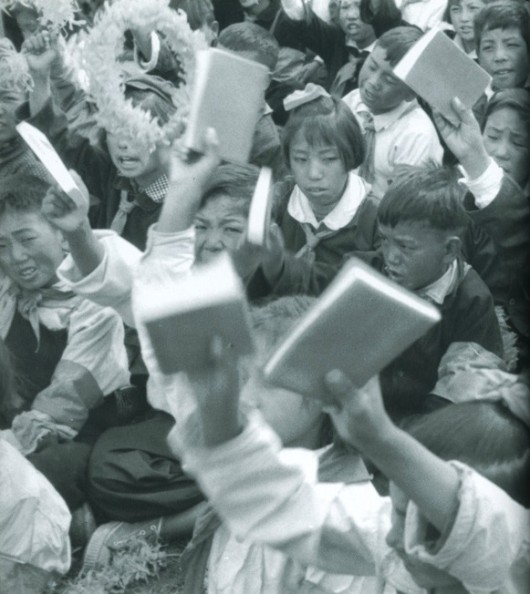

The most moving and powerful images in Foreign Policy’s slideshow depict the mistreatment of monks and nuns, who were and are the most revered members of Tibetan Buddhist society. The tragedy of the Cultural Revolution in Tibet was not just in the bouleversement of long-held values and destruction of relics, but the trauma of religious conversion: when the Buddha and the Dharma were replaced by a peculiar new god and scripture in Mao and his Little Red Book.

William is a Tibetologist on course to receive his doctorate in Tibetan and Chinese religions at the University of Virginia. He can be reached at wam6n@virginia.edu.

When Tibet Loved China (Foreign Policy; photos by Tsering Dorjee, published in his daughter Tsering Woeser’s book Forbidden Memory: Tibet During the Cultural Revolution)

These photos are great and put into perspective how effective the Cultural Revolution was at getting people from all regions involved. Even Tibetans, that in my mind have resisted China’s influence more so than most autonomous regions, take up the little red books and shout out party slogans. This is a side of the Cultural Revolution I had never thought about. This is good history.

Excellent stuff, an informative addition to FP’s piece.