On January 15, BBC News ran a report about a Trojan virus affecting millions of users in China. According to undisclosed security firms, there now exists a botnet on these millions of devices capable of “being used for fraudulent purposes,” including DDoS (distributed denial of service) attacks and spam email campaigns. Of course, this does sound scary, and botnets (in any form) are becoming more and more prevalent and thus increasingly worrisome.

The question for our readers, however, is: will this really affect me? The simple answer is: Probably, if you’re using Android. Improbable but not impossible, if you’re on iOS.

Here, in part 1, we look at Android. We’ll discuss iOS vulnerabilities in part 2.

Target-Rich Environment

The great thing about Android is also what makes it so dangerous: it is fundamentally an open platform. Manufacturers and individuals can adapt the system to their needs; software developers can make applications that fundamentally change how the device operates; users can (with a bit of technical know-how) swap between different “flavors,” from original Google-vanilla to CyanogenMod’s rocky road.

In China, this translates into an explosion of Android-based devices that, in many cases, don’t even ship with default Google Apps (emails, maps, etc.), including the official Android Store, Google Play. Many of the estimated more than 200 million Android users are getting their apps (free) from unlicensed, unaffiliated, and unregulated “stores” that, in many cases, host repackaged applications to include malicious code.

Adjacking

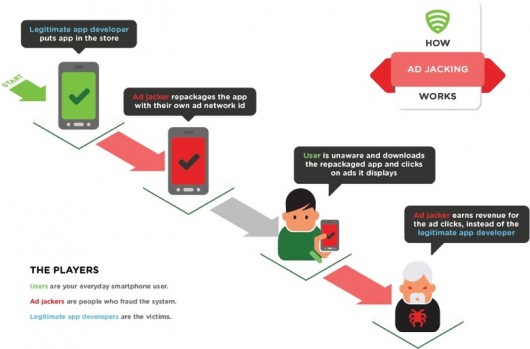

A spokesperson from Lookout Mobile Security told me that tricking someone to give up access is done in many different ways, with the most common in China being adjacking.

From Lookout’s State of Mobile Security 2012 report (emphasis mine):

App marketers (promoters) are often incentivized based on how well they are able to drive metrics that correlate to app popularity, including app downloads, installs and activations. While the incentive structures may vary, the general rule of thumb is that the more times an app is downloaded, installed or run, the bigger the reward. App promoters will use malware capable of one or more of the following malicious tactics to boost metrics without the user’s knowledge:

- Download applications from alternative app market sources to storage locations that do not alert the end user. These apps may or may not be installed, depending on the type of malware.

- Masquerade as an application that requires root permissions to gain escalated privileges on a device, which can then be used to install subsequent applications.

- Install third party app stores onto the device in an effort to convince the user to download specific apps.

- Silently run applications while the device screen is off to register “active app” events.

Lookout has dubbed the Trojan referred to earlier as “SimpleTemai.” According to Lookout, they first discovered it in September 2012, but have not seen any recent increase in activity. Now, the interesting thing about the SimpleTemai family of malware, and why we should be worried about botnets, is that it can be remotely updated:

“Although current capabilities are limited to mobile click fraud and we have no indication its creators are branching out beyond current functionality, SimpleTemai could presumably leverage this capability to significantly modify its behavior.”

Kingsoft, which calls the Trojan “Android.Troj.mdk,” reports that it has found over 7,000 apps carrying the Trojan, all of which are found in third-party Chinese application stores.

The Playdian Knot

Google Play poses a big challenge for Android in China. First, at this time, it doesn’t support purchases through its China store, thus pushing users interested in paid apps to pirating. Second, these third-party app stores that enable pirating are ubiquitous, easy to find, and easy to use.

If you are a user in China with a phone bought here and tied to a local network, there are a few different things you can do1 to get those unavailable apps:

- Remove the SIM card and turn on a VPN. For best results, you can link your Google Wallet to a US (or other supported market) credit card.

- Download and install various market unlockers. Usually thse require root access.

- Use third-party app stores.

As you can see, using third-party is by far the easiest choice. That being said, Google Play itself has been known to host apps with malicious code and other threats to privacy.

Prophylactic Habits

What is one to do? You could, as suggested here, keep as little personal information on your mobile device, encrypt everything else, and closely monitor data and SMS usage. However, while certainly good advice, the most basic and easiest thing to do is install a security application.

In my time as an Android user, I’ve used two: Lookout and TrustGo, both of which were very satisfactory. That being said, a quick search of Google Play will come up with many, most of which are probably OK.

The best advice I can give, and what you’ll hear from security experts, is treat your device like a computer, with all the infection risks that entails; install anti-virus/security software; don’t download anything of unknown provenance

1 Disclaimer: Some of these may not be completely legal and/or violate the terms of service of Google’s Android and Google Play. Their description here is not encouragement to use them and should not be taken as such.

John Artman has been China watching and covering tech since 2010. Follow him @KnowsNothing.

Wow, and thanks!

Looking forward to Part 2~