As has been well documented in discussions of the cultural situation in Xinjiang, many minority people in Xinjiang feel the future of their language and culture is insecure. Efforts to replace Uyghur-medium education begun in 2004 have intensified as the capillary spread of Chinese capitalism embeds its network and ideology deeper and deeper into southern Xinjiang.

Although the first site of conflict was urban Uyghur schools, the extension of the railroad to Hotan has brought with it the “leap-frog development” of brand-new schools staffed by Mandarin-speaking teachers; in some cases the signs which accompany this “opening up of the West” were written in Chinese rather than the legally-required Uyghur script of the Uyghur Autonomous Region. These schools are popping up in the desert towns of Southern Xinjiang as tokens of the “sister-city” relationships established around conference tables in Ürümchi following the trauma of the 2009. The sister cities build kindergartens and schools. They name them Beijing Kindergarten; Beijing elementary school; Beijing middle-high school; and leave their signs there as a permanent mark in Uyghur communities. In protest of the erasure of Uyghur-language signs at a Beijing middle-high school in Hotan, earlier this year Uyghur students – at great risk to their well-being – walked out and staged a schoolyard sit-in. Uyghur signs were promised.

Tsinghua University professor Wang Hui has described the atmosphere of Western China as being in the midst of a “cultural crisis” which accompanies rapid lifestyle changes. For Uyghur children, growing up in the midst of this revisioning, the songs they sing, the clothes they wear, and the stories they tell often feel explicitly inscribed with particular cultural values and tastes.

One of the Uyghurs’ brightest lights, the child star Berna, is a particularly good example of the emergence of Uyghur desires.

Berna is a trilingual seven-year-old from the urban upper-classes of Ürümchi; yet despite the opportunities laid out before her it is clear that her Uyghur subjectivity is most important for her (and her parents). When China Central TV interviewers ask her who her favorite singer is, she says to the bewilderment of non-Uyghur listeners: “Ablajan – he’s a great singer.”

In 2013 Ablajan, who I discussed previously as a Justin Beiber-like figure in the Uyghur soundscape, was one of the first Uyghur singers to compose a new Uyghur alphabet song. His song is short and relatively generic.1 Adding her voice to the successful use of this pedagogical tool, Berna (along with the young adult pop-star Gulmire Tugun) has enlisted her voice to another song which encourages children to engage in what Gayatri Spivak would call the “deep language learning” necessary to bring forward an indigenous epistemology. Following the lyrics (below), I will discuss the cultural values modeled by Berna and her Uyghur tutor Gulmire.

Learning the Alphabet

Give, give, take and give (1)

Take your pen and write (bar) it for me

Draw it like a red flower

Da de Spell it for me. (2)

Sing a lullaby and cradle it for me.

Stretch it, break it (in) for me

Yes, Yes, Yes

Che in Chai (tea), Sh in sham (candle)

In this pattern D in Dan (grain)

Y in Ay (moon) N in Nan (bread) it is time to conjugate M (3)

What happened, what happened

In syllable of A there is a full moon.

The moon is full the sun gave birth (4)

Now they have become one.

Ba, Ba, bring it for me

Bring the alphabet for me

If you take it from the people give it back to the people

Give it back to the people who love it

Give the language to the people who love it (5)

Purchase it again for me, buy an Alphabet for me. (6)

With knowledge (of Uyghur) prosper for me

Rise and soar for me.

(Dance breakdown)

(Arabic order) Ilp, ba, ta, sa

If my mother gives me five cents

If the candy comes by itself

Yes Yes Yes Yes (Repeats)

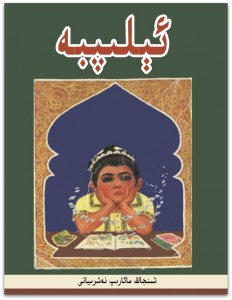

As one Uyghur listener put it, Berna’s alphabet song is even “more urgent” than Ablajan’s song. It is more about “teaching the language” than learning proficiency. (1) Gulmire begins by mimicking the language game played by a Uyghur language instructor and young children using the word Elip-be or Alpha-bet. This word originally comes from combining the first two letters of Arabic. Just as the word “alphabet” is the combination of “alpha” and “beta.” In Uyghur, if you take these initial letters apart they mean “to take” and “to give.” (2) She follows this dialogue by moving directly into the way the spelling of Uyghur letters is taught – by combining consonants with common vowels. (3) Next she begins to hint at the intricacies of Uyghur grammar by describing the way an “M” must be added to nouns in order to transform them into the first-person possessive case. (4) Turning then to the deep importance of the language, she relates these simple words to the famous 11th-century Uyghur book of enlightenment, “Wisdom that Brings Happiness,” written by the famous Uyghur scholar Yusūf Khāṣṣ Ḥājib for the prince of Kashgar. Since two of the main characters of this largely secular book of philosophy (a precursor to Western Renaissance texts) were the vizier Aytoldi (Full Moon) and the king Kuntoghdi (Rising Sun) — who stood for fortune and justice, respectively — Berna has embedded a moral lesson within the lyric. (5) Berna then makes a distinction between a language learned out of utility and a language learned out of love for a social collective. She tells us that if something is taken from the people, then the void must be made up by those who live despite this lack. (6) Finally, and most importantly, she invokes a feeling of melancholy, a feeling which precedes the loss of a barred object, with the line: “Purchase it again for me, buy an Alphabet for me.” Here she is referring to a book which is known and loved by a generation of Uyghurs born in the Dengist Reform era: the textbook known simply as Alphabet (Elipbe). The sight of the familiar green cover illustrated with an image of a young Uyghur boy with hands on his chin, lost in thought in the garden of the imagination, fills many Uyghurs of this generation with feelings of nostalgia. Many young parents can recite from memory the opening lines of the first dialogue: “One day Guljam came home from school and he proudly said…” Or Dialogue II, where their political education began in earnest: “Beijing is the capital city of our motherland China…”

As one Uyghur listener put it, Berna’s alphabet song is even “more urgent” than Ablajan’s song. It is more about “teaching the language” than learning proficiency. (1) Gulmire begins by mimicking the language game played by a Uyghur language instructor and young children using the word Elip-be or Alpha-bet. This word originally comes from combining the first two letters of Arabic. Just as the word “alphabet” is the combination of “alpha” and “beta.” In Uyghur, if you take these initial letters apart they mean “to take” and “to give.” (2) She follows this dialogue by moving directly into the way the spelling of Uyghur letters is taught – by combining consonants with common vowels. (3) Next she begins to hint at the intricacies of Uyghur grammar by describing the way an “M” must be added to nouns in order to transform them into the first-person possessive case. (4) Turning then to the deep importance of the language, she relates these simple words to the famous 11th-century Uyghur book of enlightenment, “Wisdom that Brings Happiness,” written by the famous Uyghur scholar Yusūf Khāṣṣ Ḥājib for the prince of Kashgar. Since two of the main characters of this largely secular book of philosophy (a precursor to Western Renaissance texts) were the vizier Aytoldi (Full Moon) and the king Kuntoghdi (Rising Sun) — who stood for fortune and justice, respectively — Berna has embedded a moral lesson within the lyric. (5) Berna then makes a distinction between a language learned out of utility and a language learned out of love for a social collective. She tells us that if something is taken from the people, then the void must be made up by those who live despite this lack. (6) Finally, and most importantly, she invokes a feeling of melancholy, a feeling which precedes the loss of a barred object, with the line: “Purchase it again for me, buy an Alphabet for me.” Here she is referring to a book which is known and loved by a generation of Uyghurs born in the Dengist Reform era: the textbook known simply as Alphabet (Elipbe). The sight of the familiar green cover illustrated with an image of a young Uyghur boy with hands on his chin, lost in thought in the garden of the imagination, fills many Uyghurs of this generation with feelings of nostalgia. Many young parents can recite from memory the opening lines of the first dialogue: “One day Guljam came home from school and he proudly said…” Or Dialogue II, where their political education began in earnest: “Beijing is the capital city of our motherland China…”

Berna and her minders are extremely adept sounding boards for Uyghur desires. Although to non-Uyghur listeners this song sounds like a typical early-education ditty, for Uyghur listeners “Learning the Alphabet” implies that the tutor-student relationship modeled by Gulmire and Berna is one of the only measures Uyghur people in the city can adopt to preserve their language and culture. Unlike for previous generations of Uyghur children, Uyghur is no longer taught in many urban public schools until the third grade; and even then it is treated as a second or foreign language. In the words of one Uyghur, “Some people might say, ‘Oh, she is probably just reviewing or doing homework with the help of a tutor.’ But from the context of the song, the page of the alphabet they show in the beginning of the video, it is definitely not a repetition of something she learned at school.”

Berna and Gulmire are expressing a longing for what is not yet lost. Their song is pitched to the response they evoke in young parents as much as their assumed target audience is Uyghur children. Unlike the three Xiaos I wrote about a couple of weeks ago, bright lights like Berna inspire the sort of optimism necessary to make the risks of contemporary life in Northwest China bearable.

Next week I will discuss the way Uyghur language and cultural politics are a deeply historical part of the Uyghur ethos and how they find a manifestation in another of Berna’s performances.

1 Lyrics for that song sung with the child singers Sheringul Metqasim and Sherinay Ghulam are as follows: “Let’s start. Come on over let’s study alphabet. Let’s acquire the mother tongue thoroughly. Everybody in this mother tongue, in this beautiful language, let’s speak freely and fluently. Yes! Please start! 8 vowels, 24 consonants, what a beautiful mother tongue! Study it well, know it well.”

Beige Wind runs the website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, which attempts to recognize and create dialogue around the ways minority people create a durable existence, and, in turn, how these voices from the margins implicate all of us in simultaneously distinctive and connected ways.

|Dispatches from Xinjiang Archives|

Further Reading:

S. E. ‘Bilingual’ education and discontent in Xinjiang. Central Asian Survey, 26(2) (2007), 251-277.

Caruth, C. (2010). Interview with Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. PMLA, 125(4), 1020-1025.

Zzzzzzzz.

This is a downer.

We all know this site is about fluff, booze, T-n-A, burning things, spectacular road accidents and officials (and their family) behaving badly!

We all also know ethnic minorities in China only exist to sing, dance and make the People’s Congress more colorful!

One can only wonder what 阿凡提, the star of 70′s Chinese animation masterpiece, would think of all this…

Interesting insight. Enjoy the diversity Beige Wind brings. Keep up the great dispatches.

You note that “…Uyghur is no longer taught in many urban public schools until the third grade; and even then it is treated as a second or foreign language.”

Interesting. Which begs the question: Are all students, including Han, required to attend these ‘Uyghur-as-foreign-language’ classes?

If so, that would be an important breakthrough, and it would unquestionably improve the image of the language and its speakers. I may have my facts wrong, but as I understand it, it is not standard practice to teach Uyghur to all students; classes are normally restricted to students who identify themselves as Uyghur and want to take the class.

I believe this is the case in Tibet and Inner Mongolia as well; everyone must master the national language, Hanyu, while the Han are not required to master the local language, even in the so-called “autonomous counties” where non-Han dominate. Regardless of the intent of such a policy, the message conveyed is that Uyghur, Tibetan and Mongolian is for “Them,” not “Us,” and the only “real” language is Hanyu.

Under the DPP during 2000-2008, many schools in Taiwan required students to study one of the non-Han languages widely spoken in their region. Some of my Australian colleagues in HK were also required to study an Asian language such as Indonesian before they graduated high school. The result: an appreciation, even if grudging, of others’ languages and cultures.

It’s also important to note that these policies change as a result of central government decisions. While reading Wang Gang’s “English”(英格力士,王钢著) his novel about growing up as a Han in Xinjiang during the Cultural Revolution (which he did), his Han protagonist does attend Uyghur class along with all his classmates.

@Chinese Netizen: Sorry to put you to sleep. The happy-dancing automaton is certainly a dominant stereotype, but I’m trying to say that “doing the ethnic” has deeper implications. I promise that not everything I throw up here will be so serious.

@Doctor Chaza: Apendi (En: Mister) is a common character in the Islamic world, but unfortunately one of the few images experienced by Chinese viewers of Uyghur culture (I assume that this is due to the popularity of the cartoon – http://bit.ly/fpY7R). There is a whole industry of Han entrepreneurs mobilized around selling these images to domestic tourists. My sense is that the feeling many Uyghurs get when they see these images is the same feeling Black Americans get when they see White Americans performing in blackface. That being said, it would be interesting to give Apendi a chance and see exactly what feelings he inspires in differently positioned viewers.

@Tom F.: Thanks for reading!

@Bruce: Yes this is generally the case. The majority of Han students who end up studying Uyghur in college are those who fail to test into other more lucrative majors and therefore find themselves in line for army and domestic security jobs. Since the economic and cultural incentives appear negligible, Han Xinjiangers who learn Uyghur for any other reason are quite rare. As you point out in the writing of Wang Gang but would add even more explicitly the great writer Wang Meng (http://bit.ly/1dEFbU4), Han migrants in the 50s and 60s often learned the local languages since that was part of their socialist reeducation. As a result Wang Meng is highly regarded by both Han and Uyghur intellectuals.