Over the next few weeks I will be discussing the comedy of Abdukarim Abliz, the most famous of contemporary Uyghur comedians. Abdukarim is a tall distinguished-looking man from Kashgar famous for his carefully groomed mustache. Like other suave comedians (Stephen Colbert springs to mind) Abdukarim not only embodies a masculine ideal, he parodies it. Yet for all his quick-witted use of language, metaphor, and jawline, Abdukarim has something serious to say about Uyghur society. By making them laugh, he is trying to mirror how his Uyghur audience acts, talks, and thinks about common sense issues in society.

1. The history of Uyghur comedy

In an essay titled “A Brief History of Itot” the Uyghur writer Hoshur Qariy traces the genealogy of a Uyghur form of sketch comedy, or itot, from its French origins in the 1860s to its arrival on the Russian scene in the 1920s, its derivation in Soviet Uzbekistan and eventually its arrival in Northwest China. According to Qariy, the Uyghur word “itot” is derived from the Russian translation of the French word “feuilleton.” In 19th-century France this was a social commentary section in magazines and newspapers – something similar to the “talk of the town” section in The New Yorker – and this journalistic form was adopted by the Russians soon after and eventually transformed into a dramatic art form in Soviet Russia.

According to Qariy, “if we look at the history of Uyghur drama there is no satisfactory information about the origins of the itot.” Going on, he says that famous books of ancient Uyghur history and philosophy by renowned Uyghur scholars like Imin Tursun and Abdushukur Muhammad Imin discuss comedy as an “episode” within a larger dramatic performance, but the stand-alone mini-drama or sketch comedy form of contemporary Uyghur performers has no single indigenous antecedent. This is not to say that the role of comedy has not been important in Uyghur social life over the centuries, but the “itot kichelik” or “night of comedy” which rose to the fore over the past decades through the personas of famous comedians such as Adil Mijit is a relatively new form of entertainment and social satire.

It is difficult not to see the overlap and similarity between itot and the Chinese comedy form “cross-talk” (xiangsheng). Although the Chinese form of cross-talk comedy has its origins in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), as the scholar Perry Link described recently in an interview, as it came into the service of Socialist Realism in Maoist China it became a tool with which to teach the general public moral lessons and proper Mandarin pronunciation.

Although xiangsheng, and comedy more generally (think Colbert, Louis CK), often appears to be an absurdist break from political language, in many ways its function is to put social norms and values on display, and perform the hilarity that ensues when norms and values are violated. Regardless of where “itot” came from, the same can be said about Uyghur comedy performance. The difference remains in that the itot reinforces Uyghur cultural citizenship and the knowledge systems which are tied to fluency in Uyghur language.

2. “In each month the moon shines for 15 days and is dim for 15 days”

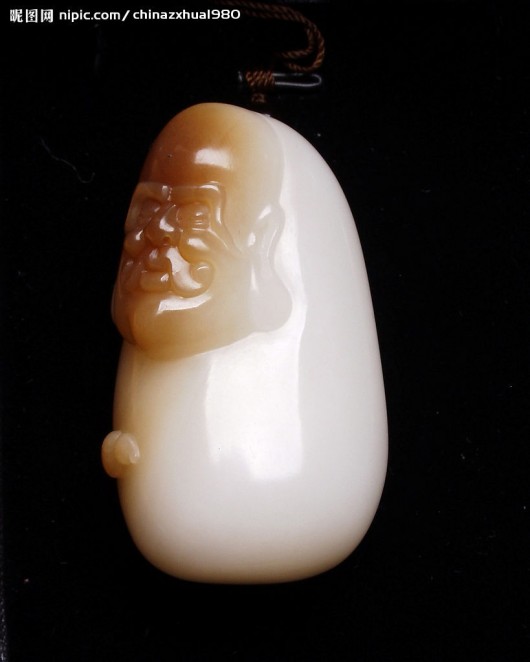

The title of one of Abdukarim’s major comedy galas in 2012 is a common saying in Uyghur, which roughly approximates the English saying, “what goes around, comes around.” The sketch begins with the character played by Abdukarim returning to Ürümchi after seven years in Beijing. After a circuitous discussion, Abdukarim admits to his long-lost colleague from Hotan that he has lost the fortune he made from selling jade in the early 2000s. He tells his friend that he has heard that his friend has invested the money he made from selling jade in a company and that this company is known for its benevolence. It is here, around the 7:50 mark, that Abdukarim begins to break down.

He tells his old friend, “I came here so you could stroke my head.” In Uyghur this phrase implies a comprehensive form of comfort – a taking care of the material needs necessary for life. It is something someone says as they are dying to their relatives and close friends: “please stroke the heads of my family.” But Abdukarim’s colleague misunderstands this request and instead literally strokes Abdukarim’s head. Abdukarim then says (8:15), “You’re messing with me. I came here so that you might take me” – a line that implies that Abdukarim wants his friend to take him as his wife. The audience roars.

By this time the audience in the Ürümchi concert hall appears quite rapt by the scene unfolding before them. Abdukarim then delivers the first moral lesson of the evening. At the 9:37 mark he says in a serious tone, “Before I passed millions of yuan through my hands, now I merely chase after hundreds of yuan. If you abuse money – money will abuse you.” As the crowd solemnly applauds, he continues the lesson: “In the business of corn and wheat you can always grow more, but in the business of stone, stones just get fewer and fewer. The best thing is for me to start a business like you; the best thing is to increase your own quality (Uy: sapa; Ch: suzhi). If you have millions of yuan but don’t have knowledge and quality you are like a donkey” (10:05).

Abdukarim’s partner does not let him get off so easily. Parroting the Chinese mainstream clichés of economic success and accruing cultural capital or suzhi is not enough to merit his sympathy. Instead he points out the deeper moral failings of Abdukarim’s character. “Oh wow, now you have become a philosopher. Before you were spending money like paper, easy, easy, easy, easy ….” (10:12) – the repetition of this last word forms a Uyghur onomatopoeia for the sound money makes as it is peeled off in one’s hand. Abdukarim’s character again diverts the blame, saying it was Satan that led him astray. Again his friend points out that it was not Satan but “those young flirtatious (nainaq) girls which misled you.”

Faced with this gendered accusation Abdukarim finally begins to admit to his failings as a man, a Muslim and a Uyghur. He offers a line which attests to his deep roots in the culture of Hotan: “Nightclub ruined my life” (10:57). “I made money with coated stones and wasted money on coatless women.” To which his friend responds, “Because those women were foreign that’s why they look like gold. They were dancing around you – that’s why you just gave them money. If you would have given the money to poor men without jobs in your hometown for food and coal, you would have earned good deeds (sawap)” (11:25). In what follows, Abdukarim admits to his womanizing and his moral failings.

What is important here is to note the way Abdukarim signals that a proper way of knowing is associated with Uyghur ways of thinking. The line “I made money with coated stones and wasted money on coatless women” refers to the most sought after jade: white stones have to have a golden coat — a yangzhiyu. This way of speaking is taken directly from the regular conversation of Uyghur jade traders. Anyone who is familiar with the Uyghur jade scene has heard people say “tashning chapini bar mo? süzük mu?” – “Does it have a coat? Is it clear?”

3. A comedy of Cutural Citizenship

The theme Abdukarim is addressing is the way the rise of consumer culture and lucrative jade businesses has impacted the moral lives of Uyghurs from Hotan. As a man who lived through the experience of economic growth and social change in Hotan told me recently, the jade industry in Hotan really took off “in the last ten years. In the 1990s it still wasn’t industrialized. People just used shovels and katman (hoes) to dig for jade by hand.” There were no giant earth moving machines.

But by the early 2000s things began to change. People invested in industrial grade equipment and it became a lucrative business. He continued, “Some people who couldn’t get jobs out of college started in the jade business and got super rich. Rich people now just get richer.” The people who have been doing it long-term are often pushed to the side. There are even whispers of organized gangs who profit by intimidation and extortion. Recent efforts to regulate access to jade sites have led to officials with heavy pockets and protests from those elbowed aside.

Cultural citizenship refers to the slippage between the performance of a given set of values, or worldview, and the lived experience of one’s legal status. Uyghurs are legally Chinese citizens of Uyghur nationality, but what does that mean in everyday life? How does one perform ethnicity, not as an interpreter for outsiders, but for other people in one’s own social position? These are the questions that Abdukarim embodies and enacts as he takes the stage. When he takes on the persona and moral economy that accompanies the process of getting-rich-quick, Abdukarim is drawing limits around Uyghur norms, and he is promoting Uyghur ways of thinking and acting. By making people laugh at themselves, he is forcing them to evaluate themselves.

Thanks as always to M.E. for help with translation.

Beige Wind runs the website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, which attempts to recognize and create dialogue around the ways minority people create a durable existence, and, in turn, how these voices from the margins implicate all of us in simultaneously distinctive and connected ways.

Thanks for posting these insightful blogs helping everyone make sense of Uyghur identity and culture. I thoroughly enjoyed a trip to Xinjiang as a ski mountaineer this past July and was blown as by the hospitality of the Uyghur people. I am editing a short video about our trip, and in doing so, am interested in understanding the Uyghur people more. I finished a trip report, with some preliminary thoughts, but am having a harder time turning it into a film. Here’s a copy of the trip report if you are interested: http://www.summitpost.org/skiing-muztagh-ata-china/872095

And here is an album of photos I shot called Uyghur Faces of Xinjiang: http://500px.com/PeakAestheticProductions/stories/102966/uygher-faces-of-xinjiang-china