The Silk Road of Pop (2013: 53 min) ends with a young rapper saying he wants the world to know Uyghurs exist. The man, a sculpted crop of hair jutting from his chin, says, “Aside from China, who knows that Uyghurs exist? Zero percent.” As a view from a train window merges into film credits while the Uyghur musician Perhet Xaliq and his wife Pezilet sing an old song of Uyghur youth “sent down” from the city, the pathos of the rapper’s plea seems to resonate with the atmosphere of the land, the tight cement block apartments, the frozen sidewalks paved with Shandong tiles. Being a contemporary Uyghur is something that young people in Xinjiang seem to think about and perform all the time. You can hear it in the air. Why doesn’t the sound they make travel back to them?

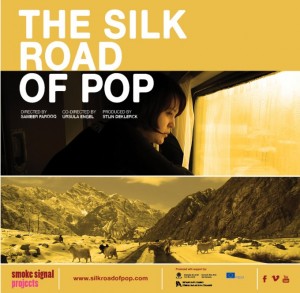

This mesmerizing new documentary film by the Canadian and Swiss filmmakers Sameer Farooq and Ursula Engel pulls the viewer in and out of the dense soundscape of Northwest China. Moving between a diverse group of fans and musicians in Ürümchi, the film is threaded by the pulse and pull of music. Through deft editing, the filmmakers introduce us to Uyghur music culture by showing in garish detail the spread of Uyghur music products in coal-stove-heated shops: plastic covered VCDs in vibrant covers by the thousand. Then we’re shown how music is consumed on cheap computer screens and grainy players. As the tinny sound of low-quality speakers morphs into stereo, the camera moves into the music video, and the featured musician suddenly talks directly to us. The audience and musician are now connected, with the thickness of the Uyghur music experience front and center, forcing us to think with the music as it envelopes Uyghur spaces.

The film’s subjects are thinking with music as well. They are interested in what it can do. Over and over again we hear about the way music is ingrained in them, how it infuses them with values and convictions. Embedded within this refrain is a discussion of how people are defined both as groups and as complicated individuals. Like ethnic groups around the world, the burden of identity, of what is experienced as “tradition,” weighs heavily on Uyghur youth. But these are also kids in a changing China. The possibilities for connection and influence seem limitless.

This is what we hear when one of the young Six City rappers says, “Yes, the stuff of our Uyghur nationality is amazing,” only to be interrupted by another member of the crew who says “it’s like being clowns.” Finishing his sentence, the first speaker adds, “But the things we do (rapping) connect to the rest of the world.” This is an argument for relevance. Young Uyghurs in the city are living in a world of connections where the possibility of becoming a “self-made” success seems simultaneously within reach and unattainable. With the buoyancy of youth, the music they create reaches out to us. While we’re on the Silk Road of Pop, we feel like these kids will make it.

Yet, despite this broadened horizon of possibility, the pressures of simultaneously being a good son or daughter, a Uyghur, a Muslim, a Chinese, and an underpaid rocker, rapper, or free-rider gives people the feeling of being out-of-place – without a social role. This film is about this lifestyle of displacement: there are plaid shirts, funky haircuts, ostentatious sunglasses, alcohol and cigarettes. Like the early producers of hip-hop, members of the indie Uyghur music scene seem to be saying, “Look at me, I can dance and tell my story to the beat of dub-step, hard-core, grunge, whatever you throw at me. My experiences translate across genres; I can be other-than-myself; I can act out.”

But rather than merely running inward toward narcissism, listening carefully to the lyrics from groups such as Six City draws our attention to lives lived under duress. Like the protest music of early hip-hop, Uyghur rappers are telling us stories of social injustice, not misogyny or irresponsibility. While early on, a classically trained tambur player tells us, “When I listen to rap I won’t think of my parents,” the lyrics and attitudes of young Uyghur rappers do tell us a story of families and friends in the shadows of a life of toil; they tell us that what it means to be Uyghur is changing: “The rhythm of life is speeding up. The rich have money, and they’re going out. While the poor are still waiting. Some are crying, enduring. Often there are many fires. To get it real, lies are exposed. Don’t get excited. Just wait till dusk. All the riots, all the cursing, for what? For my home. I’m staying here.”

The Silk Road of Pop is about the angst of individuals coming of age and about collective changes in their music. Their song is for us; but more importantly, they are singing for themselves. These kids are owning their future. They are proud of their heritage; but more importantly, they are filling the desert with a new beat.

An overview of Silk Road of Pop festival screenings and awards as well as information about a “private-public screening” initiative is available through the film’s website. The producers are currently working on setting up ways for academic institutions to screen the film for students. The filmmakers can be contacted at smokesignalprojects@gmail.com.

An overview of Silk Road of Pop festival screenings and awards as well as information about a “private-public screening” initiative is available through the film’s website. The producers are currently working on setting up ways for academic institutions to screen the film for students. The filmmakers can be contacted at smokesignalprojects@gmail.com.

Beige Wind runs the website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, which attempts to recognize and create dialogue around the ways minority people create a durable existence, and, in turn, how these voices from the margins implicate all of us in simultaneously distinctive and connected ways.

They just need to get their beer out there. Problem solved. Easy.

Next!

The Silk Road of Pop, one of the only films about the lives of China’s Uyghur Muslims, is now available to stream online! To purchase a streaming copy, simply visit our Vimeo on Demand channel:

https://vimeo.com/ondemand/silkroadofpop

If you represent an educational institution and you are interested in purchasing a DVD, please write us an email at

smokesignalprojects@gmail.com