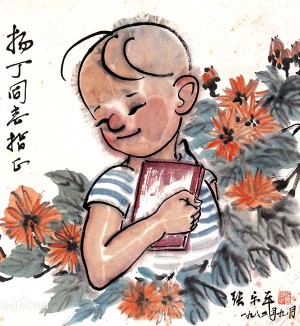

In 1935, cartoonist Zhang Leping created one of Asia’s most enduring characters: Sanmao. The emaciated boy, named for the three hairs on his head, lent a friendly face to Shanghai’s nameless street urchins and children orphaned by Japanese attacks.

But more importantly, Sanmao’s bitter adventures captured the spirit of social injustice in the city’s “golden era.”

Zhang’s earliest Sanmao comics are being shown this month in a special exhibit at the National Art Museum of China. The works are selected from 243 original strips donated to the museum in 1983.

Like the timeless commentary of Charles Schultz’s Peanuts, the dark contrast between Sanmao and his rapidly modernizing surroundings rings true 80 years later.

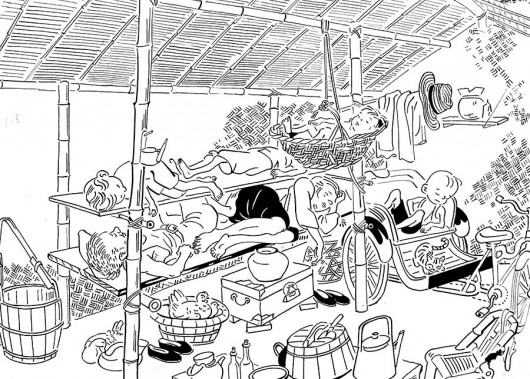

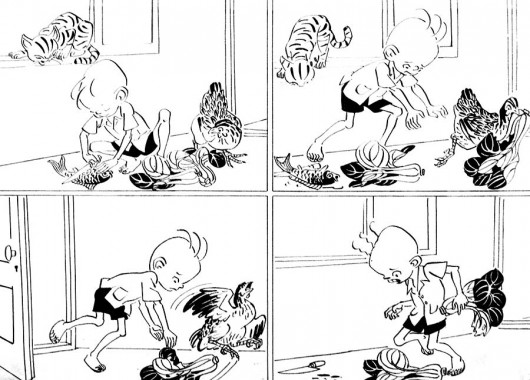

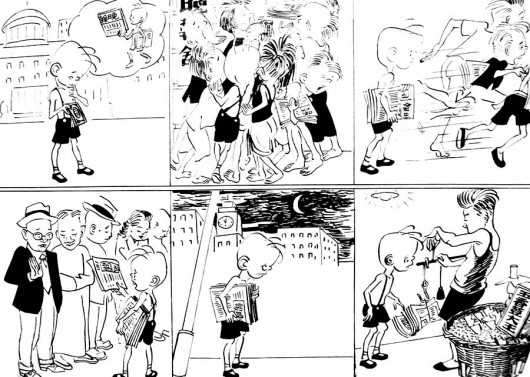

Sanmao’s world is a Shanghai in which the rich are kicking the poor to the curb. The panels convey the bitter irony of a penniless country boy striving to integrate into the “Pearl of the Orient.”

The strip transformed as China entered a state of war, and Zhang produced a series of dark and bloody comics that depicted Sanmao joining the army to fight the Japanese.

After the civil war, Sanmao evolved into a political tool for condemning old society and was seen everywhere in daily life.

The earlier works remained the most popular and found fans throughout Southeast Asia.

Zhang was born in 1910 in Haiyan County, Zhejiang province and grew up under the rule of the Beiyang Warlords.

He drew his first comics in 1927 to welcome the arrival of the Guomingdang army and satirize the warlords. Although Zhang never attended school, his father – an elementary school teacher – advised him to focus his art on the experiences of the common people to win readers.

In the early 1930s, Zhang moved to Shanghai and began drawing commercial advertisements and comics strips. Soon, most of his income came from the comics, which included Sanmao, Mengmeng Grows Up and Mustached Zhang’s Life.

His comics were published in the Shun Pao and Ta Kung Pao newspapers and were wildly popular with readers.

Zhang was eventually recruited to serve as the supervisor of the cartoon department at the People’s Pictorial Press. He became editor-in-chief of Cartoon World magazine and worked there until he died in 1992.

This post originally appeared on Beijing Today; there, you can see more sample comics from the exhibition, such as: