It took a manager in a Chinese state-owned enterprise asking me to help double-team his mistress in a Shanghai hotel for me to realize why The Wolf of Wall Street was my favorite film of 2013.

I was watching the movie for a second time – still puzzling as to why my initial viewing so enthralled me – when a random manager (or someone claiming to be such) added me on WeChat, China’s red-hot mobile messaging app. As I gazed upon Leonardo DiCaprio’s character enjoying a three-way, I fended off the manager’s requests for explicit photos to prove I was man enough to do the same. Finally, I made the connection: in spirit, if not quite in the details, The Wolf of Wall Street embodies the hidden, hedonistic thrill that drives so much of China’s official corruption.

The Wolf of Wall Street tells the story of how unscrupulous stock broker Jordan Belfort and his firm Stratton Oakmont made fortunes selling penny stocks to clueless investors, painting one of the most vivid portraits of materialistic debauchery ever committed to film. The movie confronts American viewers with the self-indulgent thrill of these crooks’ Bacchanalian lifestyles, daring them to identify with and even covet it, before taking a late, darker turn.

If only we had such a cinematic argument in China! Alas, while the government here has made fighting official decadence a priority, it still finds the subject (self-incriminating as it is) a little too sensitive to permit Wolf’s bare-all approach. China’s state-controlled film and television industry is too often tasked instead with damage control, parading a series of airbrushed imagery that casts most officials as nobly dull – not dissimilar from the sterile commercial for Belfort’s firm that opens Wolf. But Stratton Oakmont’s sanitized image of humdrum, competent worker bees is just a two-minute prelude to 178 more minutes of felonies, sex, drugs, and record-setting vulgarity laying bare the demented amoral attraction of Wall Street. In China, the bland façade is all there is.

Which is too bad, because in China we would have so much material to work with. The “wild, hyper vulgar exuberance” and “essential vitality” that critics and fans alike see in Wolf’s Wall Street crew courses through the corrupted members of the Chinese elite as well – but we can only infer it from tantalizing glimpses of the their decadence: a crashed sports car here, grainy photos of an orgy there, and everywhere rumors about the accumulation of luxury, finery, mistresses, and houses.

A Chinese The Wolf of Wall Street could actually dovetail nicely with the government’s ongoing anti-corruption campaign. Imagine a film that first revels in this simple premise: that China is an authoritarian-capitalist nation whose economic pie is growing so fast that an official can gorge himself on the proceeds with little fear of his subjects or superiors noticing; that legitimate opposition to such an official’s continued enrichment can be demonized as a threat to “stability” to be snuffed out with state resources; that here a cascade of material and carnal pleasure is filling the gap of a traditional value system decimated by years of Communism. And that all of this together is – like Jordan Belfort’s morphine – fucking awesome.

That would be the seductive message of the film’s first two-thirds, in which a young man enters the government with naïve hopes of Serving the People, only to have them dismissed by a mentor figure played by the Chinese version of Matthew McConaughey. Our official learns that China’s masses are perfectly capable of taking care of themselves, leaving his main task as extracting the greatest benefits from his official perks while learning how to arrange infrastructure and land deals to maximize the potential for GDP growth. (And taking bribes.) These would be the go-go years after the financial crisis, when China’s epic stimulus package unleashed an all-you-can-eat buffet of corruption on local governments. Sybaritic pleasures follow: banquets overflowing with endangered species and lubricated with a biblical flood of rice wine; drunken nights at karaoke parlors-cum-brothels; a mountain of luxury goods given as gifts; a pretty wife followed by a harem of underage mistresses hidden away in a growing collection of illicitly purchased apartments and villas.

(Eventually our protagonist would find himself at risk of being entangled in the Party’s anti-corruption drag net, and would seek to squirrel away his ill-gotten gains in a safe haven abroad. Canada being such a popular choice for corrupt officials on the run, perhaps we can call in Jean Dujardin to repeat his role from Wolf, this time as a banker in Quebec?)

Putting all that hedonistic excess up on the screen will be an explosively cathartic exercise for hundreds of millions of Chinese more often asked to pretend that such impulses are under control (or don’t exist). Going further, a successful Chinese Wolf could lure its audience into empathizing with and eventually envying its protagonists, until an about face near the end that hints at the shattered lives and neglected nation that are left in their wake. A final shot that echoes Wolf could be priceless, settling on a slack-jawed crowd of young civil service exam takers, lusting for the perks of official life while oblivious to their collective contribution to dragging the country into a Nationalist-style corruption meltdown. Played right, it could scare any audience straight by making people think twice about getting into government for the wrong reasons.

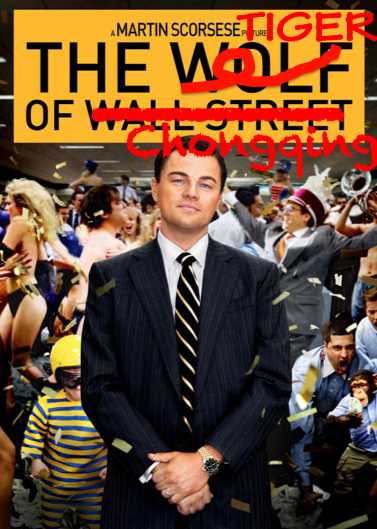

A Chinese The Wolf of Wall Street would need a new name. We’ll swap Wolf for Tiger, in deference to President Xi Jinping’s desire to rid the Party of “Tigers and Flies” (high-level corrupt officials and their small fry brethren). As for Wall Street, we’ll need to exchange America’s avenue of avarice for something with Chinese characteristics. Zhongnanhai — the Beijing compound where all the central party leaders live and work — could be a good candidate, but going after central government bigwigs is all too often still a no-no — some tigers are too big to go down. Chongqing could be an alternative. In the wake of the Bo Xilai scandal, the city in its 2007-2012 incarnation has gained a reputation as China’s high church of official corruption. The film wouldn’t necessarily have to be about Bo himself — that story is too well known and specific. But perhaps there is a self-indulgent acolyte of Bo’s (a tiger cub, if you will) whose story we could embellish to fit a three-hour film. Anyway, that would give us the name: The Tiger of Chongqing.

China’s government and its media watchdog SARFT would never let this movie happen. But what a world if it did?

Warner Brown studies real estate trends in Shanghai, but personality tests say he should have been a film critic.

Nice analysis. Very relevant.

The movie you propose sounds quite a lot like Murong Xuecun’s 原谅我红尘颠倒.

“The Civil Servant’s Notebook” by Wang Xiaofang comes pretty close to touching all the bases you mention: Outrageous official corruption, KTV party binges, gambling trips to Macau, kept mistresses by Party cadres, you name it. It passed official censorship in China, so there’s no reason why a film version couldn’t be made locally as well, although it’s doubtful viewers would get to see much T&A. The thing is, “The Wolf of Wall Street” is about characters who crave wealth in order to satisfy all the cravings of their inner (k)id, so while they may be shameless assholes, at least they know how to have fun and live life to the hilt. In China, on the other hand, government officials arguably crave power more than they do wealth itself, and as a consequence are not nearly as much fun to be around since they don’t really know how to live. After finishing “The Civil Servant’s Notebook,” I was struck by how boring and fundamentally banal these kind of people are, and don’t think they would be nearly as compelling to behold up on the silver screen.