Stagnant Water and Other Poems, 87pp; BrightCity Books. Read sample poems: Stagnant Water | Tiananmen

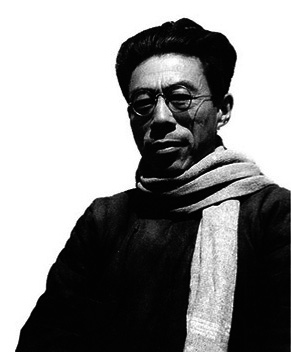

The temptation, when evaluating a poet gunned down by his government, is to start there, with the politics that led to his murder. But Wen Yiduo (1899-1946) was much too complex and heterodox to comfortably wear the martyr’s robe, his works too nuanced and unsettled to be a paragon of any revolution. His poems explore religion and rickshaws, contain the chrysanthemums of Chinese folklore and the mud of contemporary times, and dare readers to challenge prevailing conceptions, even to render their own cynicism as hope.

This stagnant ditch is hopeless. Clearly

not a place where beauty thrives.

Better cultivate its ugliness. Perhaps

its ugliness will create a world.

Mao blamed the Nationalists for Wen’s death, thus elevating him to model — if not mythic — status, yet the poet needed no such validation. He resisted easy classification. He was a writer whose ballast was in ideas and logic, while remaining fresh to the point of innovation.

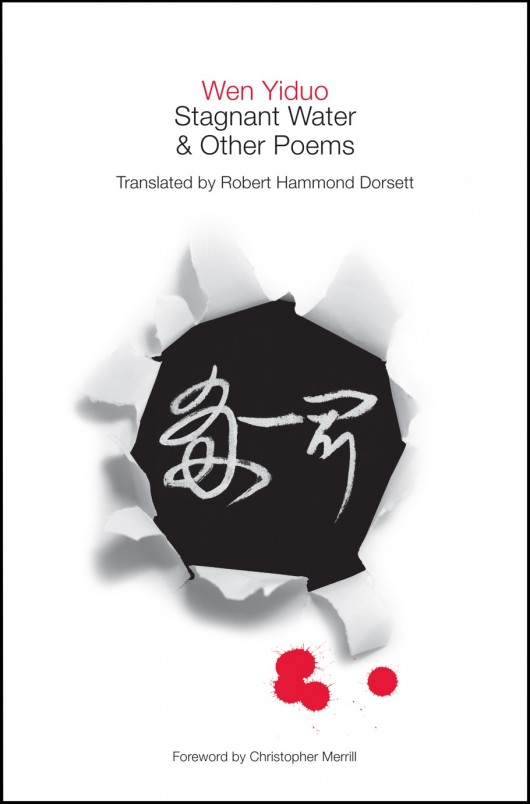

That makes his poetry both a challenge and a thrill, one that a new generation of readers can now tackle thanks to the work of poet-translator Robert Hammond Dorsett. Stagnant Water and Other Poems, recently released by BrightCity Books, contains all the poems from Wen’s second (and last) full collection, Stagnant Water (first published in 1928, rendered by previous translators as Dead Water), plus 29 other poems compiled and translated by Dorsett. It represents a long overdue attempt to bring international attention to one of China’s preeminent 20th-century writers.

That makes his poetry both a challenge and a thrill, one that a new generation of readers can now tackle thanks to the work of poet-translator Robert Hammond Dorsett. Stagnant Water and Other Poems, recently released by BrightCity Books, contains all the poems from Wen’s second (and last) full collection, Stagnant Water (first published in 1928, rendered by previous translators as Dead Water), plus 29 other poems compiled and translated by Dorsett. It represents a long overdue attempt to bring international attention to one of China’s preeminent 20th-century writers.

Born into a well-to-do Hubei family, Wen studied fine arts and poetry in the United States for three years, including at the Art Institute of Chicago, before returning to China in 1925 as a professor and critic. He co-founded a literary society that promoted formalism and deemphasized political content, yet the politics of the time would soon sweep Wen and a generation of scholars into the breach. His outspokenness put him in a line of bullets on June 6, 1946.

Wen’s abbreviated but remarkable literary career was characterized by internal contradiction, as he resisted both what the world had become and his own role in shaping it otherwise. He also knew grief: some of Stagnant Water‘s most powerful poems are about his young daughter, who died while he was studying in the US. But that was the Chinese experience in the 20th century, filled with sacrifice. The representative voice may well belong to the rickshaw puller’s, who exclaims in a poem titled “Tiananmen” about the violent crackdown of student protests:

It’s the living who suffer; to hell with the dead!

Last week I spoke with Dorsett, who began reading and translating Wen more than 20 years ago, to talk about the poet’s life, death, and legacy, and the challenges of conveying it all to an English-language audience.

What attracted you about Wen Yiduo’s work?

RHD: There’s so much I loved about the original work. It’s architectural in the sense that it’s almost like one of those gothic churches in Europe: the outside is beautiful and symbolic, and when you go inside, much more opens up, layer upon layer, and it depends on whose eye is looking.

Does labeling him a political poet undermine his artistic value? Does not calling him that lessen the recognition he might receive on an international level?

RHD: Both those statements are true, and what makes Wen Yiduo such a powerful poet is he did not resolve his conflicts. He kept his conflicts, they gave him a spark, they gave him the power and gave him the driving, lyric power of his poetry.

It’s hard to label Wen Yiduo as anything. You have to look at the conflicts within him. He was a classical poet that turned to the avant-garde but without giving up the classics. He’s a person who brought the past into the present. To bring the past into the present, you can make the future – not by staying in the past and not by staying in the present for long. He became a people’s poet, but he also was the well respected classical scholar.

You’re making the case that Wen is one of the most preeminent Chinese poets of the 20th century, but his name, at least among English readers of Chinese poetry, isn’t very well known. Would you agree with that statement?

RHD: I do, and we’re trying to rectify that with this book.

Why do you think he’s remained obscure?

RHD: Because most of the translations are done from Indo-European languages, that’s why. And I think it’s much more difficult to translate from an Asian language into an Indo-European language than it is to go between two Indo-European languages.

Another language I can translate from is German, and if I take someone like Rilke or Novalis and just translate it word for word, you get something. It sounds good. But if you do that for Chinese it sounds superficial or odd. And one of the overlying principles that I try to use is what one of our critics, Marcia Falk, said, to not make the foreign sound strange – to take that Chinese poet and make him sound like a living poet in the language he’s being put into. And that’s a little difficult.

Did you struggle with that? It obviously came together very well, but what was the process like?

RHD: You can have an idiom in Chinese that sounds very usual when it’s spoken but it sounds very strange when it’s put into English. [For example,] the poem “Quiet Night,” sometimes it’s called “My Heart Leaps,” and in Chinese when you say my heart jumps, it doesn’t have that kind of sentimental feeling that it does in English, so I think the better translation is, “I was afraid.”

The process of my translation is, I start with the text itself, I look at all the characters, and even if I recognize them, I look them up, and I get sounds. Then sometimes I get help from other people, what they think, look at other translations. Once that’s done, all the decisions, I work from the original language itself. That’s a point of integrity with me because I think it’s been in practice now for people to have other people give them an English version, and then they rewrite that version and call it a translation. I try to make sure, for myself, it’s from the original.

Have any China scholars talked to you about the book and given feedback?

RHD: Orville Schell has gotten a copy and he wants me to come to New York to do an on-camera interview. I got a letter from Phil Levine (former US poet laureate) about this book, and he said he had not heard about Wen Yiduo before but after reading the book he became a fan overnight. That was quite kind of him.

How do you think Wen’s works have stood the test of time? How have the Chinese taken to his work, and how do they feel about it now?

RHD: For all indications that I have, I think he’s a very popular poet. Most Chinese people in the United States that I speak to immediately light up when I mention Wen Yiduo. Orville Schell said he was one of his favorite poets.

As far as the test of time, he’s such a powerful poet that I think he’ll be known for as long as we’re translating, for as long as we’re reading, for as long as we’re speaking Chinese and English.

Does Wen have an American corollary, i.e. he is to Chinese poetry as blank is to American poetry?

RHD: I could fill in a lot… I think he’s to China as Wallace Stevens is to American poetry. They’re different poets, but we’re talking about reputation here.

Do you care to surmise what he might write if he were alive today?

RHD: He’s someone who would never be completely at ease. And I don’t think our times, our politics, our philosophies, are ever at ease. He would be a wonderful poet right now.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

RHD: Like all strong poets, when you get to the substrata, when you get down to the depth of the poem, [Wen Yiduo] reaches the human. When you get down that far, he’s not specifically Chinese, he’s not specifically American, he’s just human, and that’s a mark of all strong and all great poets.

Robert Hammond Dorsett was a medical officer in Vietnam before studying Chinese at the Yale-in-China Program at the Chinese University in Hong Kong. He holds an MFA from New York University and has been published in The Literary Review, The Kenyon Review, Poetry, and elsewhere. He is also a licensed medical doctor.

Robert Hammond Dorsett was a medical officer in Vietnam before studying Chinese at the Yale-in-China Program at the Chinese University in Hong Kong. He holds an MFA from New York University and has been published in The Literary Review, The Kenyon Review, Poetry, and elsewhere. He is also a licensed medical doctor.

Stagnant Water and Other Poems can be purchased from Amazon or BrightCity Books.

Thanks for that Anthony – very refreshing and informative.