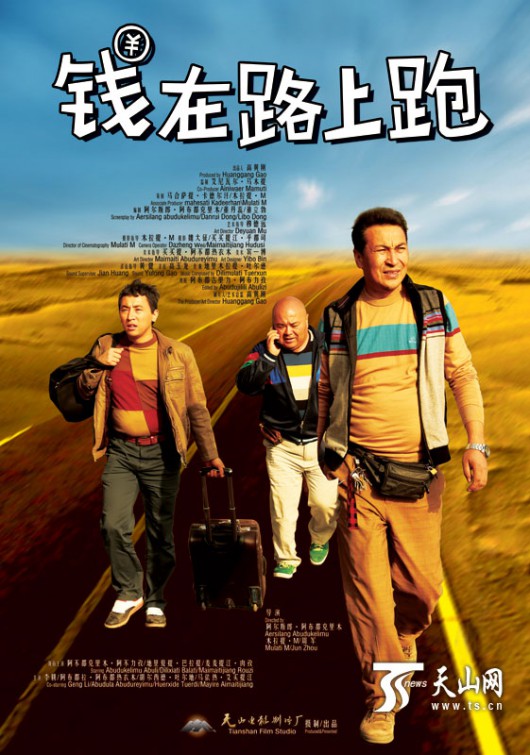

A few weeks ago, just in time for the long ten-day break for National Day holiday and Qurban, the Uyghur comedian Abdukerim Abliz released his first full-length Uyghur language feature film (with Chinese and English subtitles). The comedy Money on the Road (Money Found on the Way in Chinese) features an ensemble of stars, including a cameo by the famous singer Abdulla. It follows the misadventures of three Uyghur farmers who come to the city as migrant workers to participate in Ürümchi’s urban renewal.

Abdullah, who plays the role of a construction manager named Musa in charge of the demolition of degrading one-story housing on the south side of Ürümchi’s ring road, invites the three down-on-their-luck farmers from his hometown near the Kucha to work for cash. Although they arrive in the city with “open eyes,” as greed is defined in Uyghur, anticipating quick money, they soon find that migrant labor is hard work. Then, suddenly, the plot turns when they unearth a case of second-edition renminbi in the rubble of one of the pingfang owned by an old Han man who came to the province during the early days of the PRC. Suddenly the three feel as though they have struck it rich. Friendships are tested, hijinks ensue, and the three suddenly find themselves wined and dined by a newly rich Han businessmen intent on taking advantage of their naiveté.

A businessman fetes them at a five-star hotel, where they gorge on all-you-can eat polu and try an exclusive mud bath. Eventually they find themselves fleeing from the businessman and their cousin Musa, who wants to return the money to its rightful owner. Stumbling across the desert, they find themselves stranded. Yet China Mobile rises to the challenge, and even in the midst of the Taklamakan they are able to call in a helicopter rescue. The money is returned to the Lao Xinjiang grandpa, the rich businessman goes mad in the desert, and the farmers from the countryside are given government subsidized housing. And so the story ends with all the loose ends tied in a neat little bow.

In many ways the film extends Abdukerim’s work in sketch comedies, or etots, for which he has become so famous over the past decade. As in those plays, he asks viewers to consider the organizing forces in Uyghur society and question the way those emerging trends are interacting with older sets of values.

The theme of this film is the way so many rural Uyghurs are no longer satisfied with village life and salaries that provide enough for a family but not enough for a new car, wide-screen TV, or ability to travel and experience city life. The three main characters named Kerim, Selim, and Alim are all deeply dissatisfied with their place in a village where time is organized by cock fights rather than the rise and fall of the stock market. Their desires are symptomatic of wider forces of dissatisfaction in Uyghur rural life: everyone wants to bring more of the world into their lives, and the main way they see this happening is through the gravity of money. Abdukerim points out this obsession with money through the gleaming gold teeth of Selim’s future mother-in-law, with the way the Kerim and Alim are able to abandon their families in order to work in the city, and the way they are almost driven to abandon their friendships in order to consume more.

As in much of his previous work, Abdukerim highlights the way rural Uyghurs encounter the broader Chinese world. He makes fun of the way the businessman refers to the main characters as Ke-limu, Se-limu, and A-limu: the three Limu-s. He shows us how ridiculous a lavish five-star hotel can be and how funny it can be to see newly rich farmers in that space.

Yet the movie is also a departure from Abdukerim’s past work. While his previous comedy turned on cleaver phrasing, metaphor, and puns in spoken language, in this film we see him turning to visual puns and slapstick humor. For instance: at one point we see a rural Uyghur man riding on the back of a donkey on the back of a truck; we see Kerim trying to revive Alim by flapping his arms in the desert; there is a wedding scene where Selim dances mad with grief over the loss of his girlfriend in a parody of Sufi ecstatic passion. There are numerous instances in which bodily humor is invoked: someone gets hit on the head, a bed collapses, a stomach gets comically enlarged, and so on.

At one recent screening of the film, everyone from ages 2 to 70 was laughing; they wept when the figures on screen cried; they called in response to the pleas of the characters as the melodramatic tension tightened near the end of the film. Of course, the absurd propaganda elements – suggesting Uyghur migrants might receive the jobs that nearly always go to Han migrants, and the helicopter rescue of three rural farmers — are premises that do not resonate with Uyghur realities, but these concessions to the Xinjiang Ministry of Culture did not appear to stop anyone from enjoying the film.

Money on the Road, featuring Chinese and English subtitles, is now showing in select Ürümchi theaters. Stay tuned for its worldwide release on social media forums.

Beige Wind runs the website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, which attempts to recognize and create dialogue around the ways minority people create a durable existence, and, in turn, how these voices from the margins implicate all of us in simultaneously distinctive and connected ways.