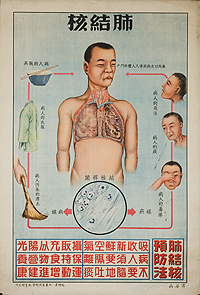

While China’s domestic media reels over the threat of ebola, praising the government’s efforts in fighting a cold it hasn’t caught, tuberculosis (TB) remains by far the country’s deadliest disease, having claimed the lives of approximately 45,150 in 2012, according to the World Health Organization.

TB is the second leading cause of death among infectious diseases in the world. HIV/AIDS is the first. But unlike AIDS, tuberculosis has a cure. In fact, it’s had a cure since the early 1950s. It’s also easily transmittable, not just through feces and blood like ebola, but through coughing, sneezing and breathing.

So why does the media focus on ebola instead of a treatable disease that’s killing 120 Chinese citizens each day?

“The international media find it easier to focus on the acute and present than on the historical problems that TB presents – the former being perceived as a ‘sexier’ and more ‘newsworthy’ subject,” said Dr. Christopher K M Hui, who works in both the academic and clinical sides of respiratory medicine for Hong Kong University.

And while China’s news media isn’t always keen on following the international news media, when a story like ebola rolls around — one that combines the shock value to distract people from more pressing issues with the highly likely chance that authorities will end up looking competent — they’re more than happy to hop onboard.

Long-Term Problems Aren’t Sexy

In 1990, TB killed 360,000 people in China. So the country has made progress. In fact, they’ve made a lot of progress. But more can be done.

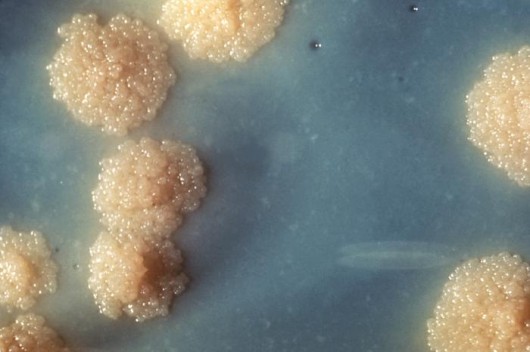

“The challenges in regards to TB now are with identification, diagnosis and monitoring patient compliance with therapy, which is required over a long period of time for successful treatment,” said Hui. Even unsubsidized, these measures only amount to a few yuan daily, he said.

The working class is most susceptible to TB, but it’s not like they can’t pay for treatment, Hui said. It’s that they aren’t educated about the necessity of completing treatment. To fight TB, you need to have doctors willing to tell their patients the importance of taking all the medicine – three to four pills a day for 6 to 12 months. But more than that, you need a media that tells people, “Ebola is scary, but keep TB in mind and here’s what to do when you get it.”

As it turns out, money is being thrown at the TB problem — the central government increased spending on TB control from 40 million to 580 million in 2010 — but it’s unclear whether it’s being spent optimally. According to the British Medical Journal (BMJ), in 2011 China’s rate of “public awareness on general knowledge” about TB was as low as 57 percent. In that year, only 47 percent sought treatment when infected and only 59 percent completed their treatment. The BMJ calls this lack of education a “major handicap” for TB prevention and control in China.

In an extreme example of what lack of education can lead to, a man in Gansu killed his wife and three children in 2011 because they were infected by tuberculosis, which he thought was incurable.

And in 2012, a young man who had just been accepted to the Ph.D. program at Hong Kong University, Wang Hao, was fatally stabbed by a 17-year old patient he had never treated. The patient was upset, in part, because he was told to return for treatment to cure his TB, which he had contracted after receiving treatment for an unrelated illness at the Harbin hospital where Wang was working. When his father was asked who he blamed for the death, he responded, “I blame the health care system.” His killer was uneducated, frustrated, and thought that doctors were tricking him by insisting he return over a course of months to treat his TB.

“Slow Motion Car Crash”

Tuberculosis isn’t like ebola, which kills roughly half the people it infects. There is no specific cure for ebola. That’s scary out of context. But unless you’re slumming it in Sierra Leone, Guinea or Liberia, there’s little reason to be obsessed about the disease. (The American media would do especially well to remember this, as the Norwegian Nobel Committee recently chided.)

“People are naturally — fatalistically? — drawn to emerging medical problems such as ebola that capture the imagination,” Hui said. “A car crash in slow motion is never quite as appealing as the ‘full speed’ Hollywood explosions that you see on-screen. TB is a little like a car crash in slow, slow motion.”

Kevin is a freelance journalist and an editor for Shenzhen Daily. He lives in Shenzhen. Follow him @kevinpinner.

hope chinese goverment can find this mistake