The first Uyghur contemporary art exhibition was launched at Xinjiang Contemporary Art Museum on May 16, attended by several hundred people from across the province, including most of the represented artists. Since the majority of the painters were teachers or professors, many leading administrators from local universities were also present. Aside from them and a few Han painters from local art schools that the museum’s leading curator, Zeng Chunkai, had invited for the opening, nearly everyone was Uyghur. Even a famous Uyghur public intellectual, Yalkun Rozi, came and praised the artists – although he clearly didn’t understand contemporary art.

Everyone I spoke with was thrilled by the opening. Several viewers were amazed to see Uyghurs given voice in a professional contemporary art space. Just seeing their work on the wall was a major thing. The artists I spoke with felt as though the exhibition — which will last until June 16 — was a turning point in the Uyghur contemporary art scene. To them it presaged greater recognition and further development outside of Xinjiang and into the world.

Actually the exhibition was made possible by an earlier one in Berlin, which included many of the pieces shown in Ürümchi. That show gave a group of five Uyghur artists an opportunity to travel to Europe, show their work, and become acquainted with the European art scene. They were given the confidence to later join the Xinjiang Contemporary Art Museum exhibition.

Although organizers received some push-back for not including Han artists, the show was allowed to go forward. (And to be fair, Han artists’ group exhibitions rarely include Uyghur artists.) This might have been due in part because of the exhibition’s diversity – several female Uyghur artists and non-Uyghur minority artists are included — and because of the artists’ previous success in Europe.

At the opening, much of the commentary revolved around what made art “contemporary” or “modern.” Many of the Uyghur artists had difficulty distinguishing between the two, but to a curator like Zeng it was an important distinction. For him modern art is uncompelling because it is derivative of earlier works or styles. Of course, it’s interesting to see a Uyghur artist in conversation with someone like Gustav Klimt, but for Zeng it doesn’t push the boundaries of what can be represented far enough.

One of the leading Uyghur artists, Dilqun Ghazi, said much of the same thing at a reception following the opening. “What makes something contemporary?” he asked. “I’m a contemporary person. I’m living right now. But that is not the same thing as contemporary art.”

He went on to say that to be contemporary, art had to meet certain criteria:

First, it has to be consciously in relationship with the art that came before it. “What we call contemporary art just began in the 1980s, so we need to be aware of what has been painted over the past 30 years,” he said.

Second, and for him most importantly, “contemporary art needs to be an expression of an individual’s idea.” It can’t pander to an audience or borrow its style from some other painter.

Ghazi, who is the son of the pioneering painter Ghazi Exmet, mentioned that, over the past decade or so, Uyghur painters have developed an affinity for painting thousand-year-old houses using the same palate over and over again. He felt that they have decided certain shades of brown and beige are beautiful. He also noted that Xinjiang painters have also gotten used to signaling their subject matter by putting a doppa on their subjects. This seemed lazy to him, and was a clear indicator of a painting that was not really contemporary. “Actually, what we take to be traditional painting is really just modern art,” he said. “For us modern art was where tradition comes from.”

Another painter, Dilmurad Abdukadir, spoke up at this point to talk about his own work and how he doesn’t really care about his audience. What was most important to him was whether or not he himself was happy. He said that, if he starts worrying about whether or not his paintings have “ethnic characteristics,” he starts to limit himself. If he just stays within his own mind though, he feels “limitless.” This gives him a kind of freedom in his painting to paint toward the affect of his inner world. For him, painting becomes a release.

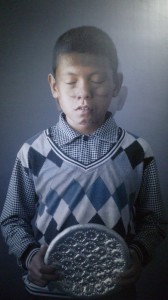

Untitled by Dilmurad Abdukadir

The painters were all intrigued by a Uyghur painter from a nearby town called Changji who goes by the pseudonym Ali K. His work focuses on the dreams of children and how they are shifting under global capitalism. Although he is clearly focused on Uyghur subjects – the school children at the middle school where he teaches — his themes were quite contemporary.

Over the course of the evening, other Uyghur artists peppered him with questions regarding his process and how he came to his current place in regards to contemporary art. For them, what stood out about his work was not only its aesthetics, but also its message: a commentary on the contemporary world and the endless commodification of everything around us, and a meditation on what is going on in the minds of children at this moment when everything that had appeared solid is melting away. Even naan, a staple of the Uyghur diet for more than 1,000 years, is now being commodified and sold on Taobao.

A painter named Bakhtiyar Abdurahim, one of the organizers of the exhibition, said that what they are painting needs to come out of the experience of urban living. It must reflect the changes they themselves are facing. As Dilkhun Razi put it: “What we are painting now is not merely an ‘ethnic spirit’ but the ‘spirit of our grandchildren.’”

By Xinjiang standards, the exhibition has already been a tremendous success. A group of Uyghur artists is participating in a space that has up to this point been the domain, nearly exclusively, of Han artists. Now their images are being seen by the wider cultural community. Shows like this build confidence. They amplify the visions of people not usually noticed. Even the Party Secretary of the Province, Zhang Chunxian, is coming to see the show. Uyghur contemporary art is now officially alive.

Beige Wind runs the website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, which attempts to recognize and create dialogue around the ways minority people create a durable existence, and, in turn, how these voices from the margins implicate all of us in simultaneously distinctive and connected ways.