Initially many Uyghurs were excited about the Uyghur photographer Qurbanjan Semet’s book-length photo essay I am from Xinjiang on the Silk Road. They were thrilled to see Qurbanjan’s national primetime interview on CCTV News. They were astonished to see it translated into English (by Wang Chiying) and sold alongside Xi Jinping’s boilerplate biography at Book Expo America. They wanted to know why people as famous and distant as the movie star Jackie Chan and novelist-turned-harmony-spokesperson Wang Meng were singing its praises.

But when they actually had a chance to look at it, many felt disappointment.

The book (which was produced largely for Chinese- and English-reading audiences) is presented as the portraits and stories of human life in and from Xinjiang. Yet, although the majority of the 100-plus people portrayed in the book are Uyghur, only a small handful are uneducated people from the countryside. So while many Uyghurs agree that the message the book carries – that Uyghurs in general are not “Separatists, Extremists, and Terrorists” – is good, they also feel that it paints a false picture of what life is really like. To borrow a metric from another context, they feel as though the book is representing the life of the “one percent.” It presents the success stories, not the failures and blockages. It shows us an image in which everyone has a college education and a good job in a Chinese company; there are few stories of poverty or the way Uyghur bodies are violently prevented from leaving the countryside; there are no stories that demonstrate the heartache that comes from the way young Uyghur men are chronically underemployed, detained, beaten, humiliated, and jailed. Oddly, if we chose to believe the accounts we are given, most of these successful people represented in the book still seem to see themselves as representative of what everyone can and should achieve — not recognizing that they are the exception, not the rule.

But still, some interesting themes do appear.

The book is broken up into six sections: a brief autobiography of Qurbanjan, followed by portraits and biographical sketches around the themes of “Inseparable Bond of Love,” “Footprints for Future Generations,” “Home is Best,” “The Long Journey to Dream Fulfillment,” and, finally, “A Feel of Xinjiang through Differences.”

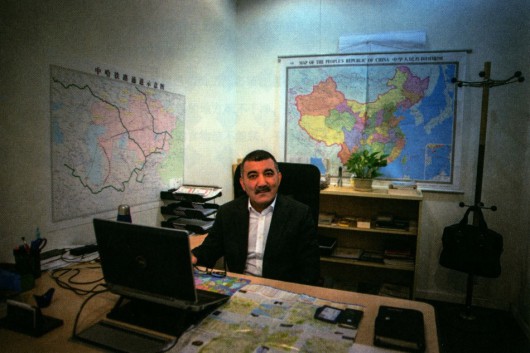

In the section on “love” people focuse primarily on love of family, their homeland, and their country. The following sections are where fragments of struggle and conflict begin to appear. A Shanghai-based businessman Perhat Kayum is one of the first Uyghur faces to break his smile. He tells us of how it was impossible for his daughter to get a Shanghai hukou and how this forced them to move back to Ürümchi where he was shocked to discover that Uyghurs are treated with even more suspicion and disrespect by security personnel than in Shanghai. He said: “To my surprise, such monitoring took place not just in the inner provinces, but was actually more frequent and in-depth in my hometown. I could do nothing but let it happen. I simply can’t explain why these things happen, nor do I know how to face them.” The struggle for Uyghurs to obtain an urban hukou and thus receive permission to apply for a passport was a frequent theme with the highly educated sample of the book. Elijan Ibrayin and his wife Mayra Ezız, among a dozen or so others, talked about the struggle to get their hukou switched to Xi’an so they could apply for passports.

Another theme that emerged from the ideological framing of the book was about transgressing racial boundaries. There were several stories about Han born in Xinjiang who converted to Islam. About how in the 1960s and ’70s there were numerous intermarriages between Uyghurs and Han and how their families have worked out a way of living despite “opposition from families and friends on both sides.” One of the most interesting stories on this theme is the story of Ai Kezu, a 35-year-old woman who changed her ethnic status from Uyghur to Han as an adult. Born to a Uyghur father and Han mother who met in the 1960s, Ai Kezu, grew up in Kashgar “rejected, blamed and abused.” Her mother, who was one of the “Shanghai girls” that was “tricked” into coming to Xinjiang to marry a soldier, is still a devout Buddhist while her father remains a devout Muslim. Eventually, she said, her family was forced to leave Xinjiang and relocate in an area in a Han-dominated province. Other mixed ethnicity families such as Yang Xiangfeng and Mayshegul Tursunjan have done the same, although in most other cases, the Han member of the new family converted to Islam.

Yang Xiangfeng and Mayshegul Tursunjan

The last two sections of the book are the most interesting. Here we read fairly straightforward assessments of violence and racial prejudice in Xinjiang. Young Han, Hui, Tibetan, and Uyghur former residents of Ürümchi weigh in on the riots of 2009 and how discrimination was built into the fabric of their childhoods. The best stories here are Hui musician Ma Jun’s telling of how lack of respect often turns to violence in the context of Xinjiang, Ilham Izak’s profound distaste for nationalism of any sort, and the Tibetan Xinjianger Zhang Caiyun’s frank telling of how stereotypes have infected her life, and Dilraba Rehmet’s absolute disgust with state-run Chinese media. These are stories in which the subject represented in the portrait has not yet disappeared beneath the cloying cheerfulness that pervades political speech about Xinjiang. These are stories and faces that stick out.

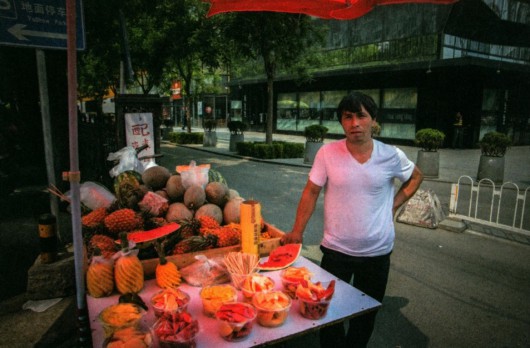

Of course, a more honest telling of the Chinese story of everyday racism and oppression is not something that can be published in China. Occasionally there were hints, in the own words of the photographed, about how Han migrants such as Liu Hongliang can be condescending to Uyghur migrants such as Repukat Alken; or how the chengguan target Uyghur street-hawkers such as Rozimurat Nahmet. But much raw feeling seems to seep through despite Qurbanjan’s and his editors’ efforts to dismiss racism as a cause for state violence and its response; and how that response has invaded the lives of everyone who comes from Xinjiang.

Liu Hongliang and Repukat Alken

The English language version of I am from Xinjiang on the Silk Road can be purchased from Amazon. The Chinese language version of the book is available in every bookstore in Ürümchi and every online Chinese bookseller.

Beige Wind runs the website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, which attempts to recognize and create dialogue around the ways minority people create a durable existence, and, in turn, how these voices from the margins implicate all of us in simultaneously distinctive and connected ways.

“It shows us an image in which everyone has a college education and a good job in a Chinese company; there are few stories of poverty or the way Uyghur bodies are violently prevented from leaving the countryside…”

What exactly is the purpose of saying “Uyghur bodies” instead of just “Uyghur” in this sentence?

It might not be absolutely necessary to say “bodies,” but by doing so I was trying to highlight that the state is policing the appearance of bodies themselves by preventing people that can’t physically pass as “Han” from leaving their home counties and prefectures. Rural Uyghurs whose bodies are marked by traditional forms of masculinity through facial hair or femininity through veiled hair are particularly susceptible to such ethno-racial profiling. Uyghurs who present themselves in ways that are seen as “urban” or “educated” from Han perspectives are less likely to be arbitrarily detained at checkpoints. That’s why I want to highlight that it is about “bodies” not just ethnicity.