In a 3,600-word piece, Cathy Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy of Britain’s The Sunday Times lay bare the myth of Neil Heywood. They argue that far from being an intrepid power broker living astutely within the inner circles of China’s elite, the murdered Briton was a “failed businessman,” a “chancer,” an “irritant,” and a liar who lucked into his connection with Bo Xilai, and was killed after a miscalculation on both his part and Gu Kailai’s. The piece, titled “Lost in China,” reads at times like a direct repudiation of the Wall Street Journal’s story last week, “Briton Killed in China Had Spy Links.” (Both are paywalled; we wrote about the WSJ piece here.) Writes The Sunday Times: “[Heywood's] 007 numberplate — even his mobile phone number ended with the same digits — fuelled fanciful stories that he had been an agent of British intelligence.”

After a year-long investigation for Channel 4′s Dispatches, based on numerous conversations with friends, business colleagues, diplomatic sources and a Chinese contact who knew both Heywood and the Bo family intimately, we can reveal the real Neil Heywood.

Far from being a top-level fixer or spy, he was a failed businessman who found himself caught up in a situation he could not control. He then made a fatal miscalculation that led to his murder.

According to The Sunday Times, Heywood arrived in China from England in 1992 and moved to Dalian in 1995, where he taught English. When he traveled to Beijing in 2000 to register a marriage with a Dalian girl by the name of Wang Lulu, he caught the attention of the British embassy, seemingly for no other reason than because he was a Briton in a place where there were few.

Kerry Brown, first secretary, was intrigued.

“At that time there weren’t a huge number of British business people based outside Beijing,” Brown said. “Neil Heywood seemed a pretty positive character, very British.” However, when Brown visited Heywood in Dalian months later and found him wandering about in jeans and a jumper, he wondered about his business acumen: “He seemed to just be drifting by.”

The story continues. Eventually, “after reading in a newspaper that Bo Xilai’s son had gone to England and was studying at Harrow, Heywood spotted an opening.” He got in touch.

The Sunday Times compellingly argues that Heywood did not, as has been reported elsewhere, help Bo Guagua get into Harrow. “Guagua was already at the school by the time Heywood came on the scene. In fact, he met Guagua and his mother in 2002 at a Chinese restaurant: the Royal China, in Baker Street, London.” But Heywood’s connection with the boy was nonetheless significant, because it would lead to his demise.

Nevertheless, Gu agreed to help Heywood out of his financial struggle, in acknowledgment of the years he had looked after Guagua. In late 2007, she introduced Heywood to a property developer who wanted to build a vast estate of Englishstyle houses outside Chongqing. “It was purely a gesture of friendship,” the source said. “She was never a participant in that project, nor a beneficiary.”

Everything Heywood touched seemed doomed. By 2008, he had been shut out of the development for failing to bring the British investment he had promised. That summer, when the bill arrived for his children’s school fees, a distraught Heywood sent an email to Guagua, asking that Gu “compensate him in cash for the failed project and for his years looking after Guagua”, according to the source. He asked for “tens of millions of pounds”.

The family was staggered. “It was absurd to ask for an extraordinary amount for merely having run the most convenient of errands, and even more extraordinary to ask Gu Kailai for compensation for the exclusion from a project,” the source said.

Sensing a growing crisis, Guagua sought to get his mother and Heywood together at a teahouse near Tiananmen Square during the Beijing Olympics of 2008. Heywood backed down. He apologised to everyone.

“Neil suggested that he didn’t really mean all the sum he asked and he was just seeing if they could lend him a hand,” the source says.

In April 2010, Heywood returned to Britain, after his firm had been temporarily struck off the companies register for failing to post its accounts. He was forced to pay for an expensive High Court appeal to get the judgment suspended so he could settle his debts without incurring a credit blacklisting.

We pause here to note that the picture we get is not of a cunning baron who wielded actual influence, but a bumbling, desperate expat who found himself suddenly knocked off his pedestal occupied by China’s many “exalted laowai” — those who, arriving early to the scene, were often overestimated by the many people they encountered simply because of their foreignness.

As it turns out, the Bo family also overestimated Heywood — wrongly — and that cost Heywood his life:

His debts mounting, in early 2011 Heywood emailed Guagua, again demanding money. This message was far more aggressive than the first. It was to prove a fatal mistake. Guagua, according to the source, told his mother about the emails in the presence of the Chongqing police chief, Wang Lijun, who had investigated Gu’s poisoning and become close to her. A few days after the Heywood conversation, Wang asked to see Guagua to talk about security. The source said Wang was determined to persuade the Bo family that Heywood was a dangerous character.

“When Guagua voiced scepticism that Neil could have been a threat, he [Wang] would reply something like, ‘You don’t know their tactics’ or ‘The people who seem the most innocent can be the most dangerous’.”

The Sunday Times built its story on a rolodex of anonymous sources, some sounding downright dopey with quotes such as, “[Gu Kailai] just doesn’t have a trace of violence in her,” but the article is internally consistent. At the very least, the image of Heywood as opportunistic foreigner is more recognizable to many of us than the image of him as suave businessman-cum-informant. RFH, in one of our earliest pieces on this scandal on March 28, alluded to this:

Heywood worked for Hakluyt, a corporate intelligence firm founded by former MI6 officers (so kind of like the Feather Men, then?) supposedly as what the Chinese poetically call a “white glove,” but we – you and me, guv – would call, more prosaically, a bagman. There’s nothing surprising about this. The British economy is run on agents, consultants, go-betweens, middle men and people who generally have nothing to offer except inserting themselves between mutually beneficial parties and making off with a fixer’s fee. The question here is, why are the likes of Bo running with this (apparently) small fry?

It’s a question that has, apparently, bothered The Sunday Times, too. If Heywood was so damn good, as other media would have you believe, how did he keep such a low profile, inspiring neither confidence nor, it seems, memory from most of his acquaintances?

The Sunday Times concludes:

All that is certain is that Neil Heywood, an idle, wellmeaning chancer, fell into a trap, partially of his own making, and that his death triggered the biggest scandal to hit China since the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989.

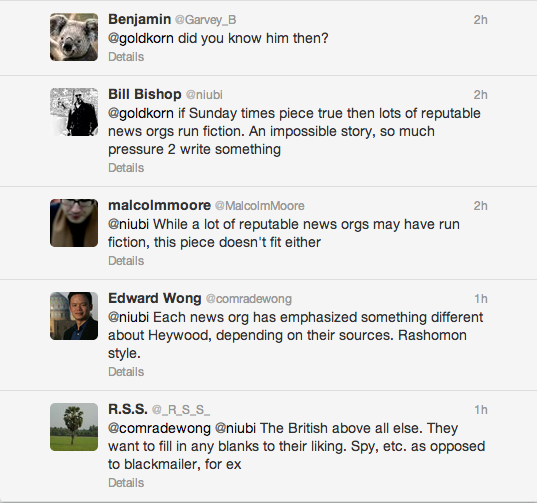

You’ll believe it if you’ve known people like him. “Sunday Times piece on Neil Heywood only reporting I have read about him that rings true (laowai in China in 1990s small circle…),” tweeted Danwei founder Jeremy Goldkorn. The responses suggest that the story you choose to believe reveals more about yourself than anything else:

If Heywood was a spy, the MI16 would surely have the Times run a story to ridicule the idea he was. Just sayin’

True or not, the entire Neil Heywood story is a movie waiting to be made.

I’m sure that Hollywood are in pre-production with this already. Who could best play the part of Heywood?

I demand a comedy version with Jim Carrey as Heywood and George Takei as Bo.

This would be worth it if only to see the Politburo’s faces.

Where does the English Teaching come in, or was that just a convenient headline to lure in the China laowai crowd?

>>According to The Sunday Times, Heywood arrived in China from England in 1992 and moved to Dalian in 1995, where he taught English.

Specifically, via the Times: “Heywood had no trouble finding himself a job teaching English at Dalian Experimental Primary School in the central Xicheng district. // By the end of the 1990s, he had put down roots. He was dating a local girl, Wang Lulu, with whom he would have two children. He told colleagues he wanted to open his own language school but nothing came of his plans.”

“he wanted to open his own language school but nothing came of his plans”

Yep, sounds like an English teacher to me.

“English Teacher” is shorthand for degenerate.

‘You don’t know their tactics’ or ‘The people who seem the most innocent can be the most dangerous’.”

Wang had his own movie running in his head.

Pretty fair estimation of Heywoood General, but explain this bit.

“Guagua, according to the source, told his mother about the emails in the presence of the Chongqing police chief, Wang Lijun, who had investigated Gu’s poisoning and become close to her.”

Who was poisoning Gu before she poisoned Heywood (after fucking him senseless of course, which is what all spiderwomen do.

One theory is that it was Bo Xilai’s first wife, Li Danyu, and/or their first son: http://beijingcream.com/2012/10/nyt-story-on-bo-xilai-classic-tale-of-love-loss-and-poison/

Wait, so Kerry Brown considers Haywood to be a “drifter,” on account of him wearing “jeans and a jumper?” What exactly did Mr. Brown expect Haywood to be wearing? A safari suit and a Pith Helmet? It’s not as if he was wearing sweatpants, I mean, what is this, the 1800s?

“The loose creases along his trouser leg suggest a certain recklessness – not to be trusted.”

In British foreign office circles it’s ALWAYS the 1800s. Afternoon tea-time, specifically.

or perhaps he was both a super spy and a wannabe laowai? lots seem to be just that. one day a nobody, the next rich on hedge fund payout, as long as you have any real info half a day quicker than the rest suckers

While I am sure this story is closer to the truth I still think it is somewhere in between the spy and the idiot. He definitely was not a spy but may have been asked some questions about the family from actual spies. The things missing from this are where does his wife fit in? His wife was from dalian and good friends with Bogu Kailai so how does his wife influence things and what was her role in all this bullshit. When your friend’s husband calls making threats for money dont you think you wont immediately call you friend and ask them wtf is wrong with their husband?

“When your friend’s husband calls making threats for money dont you think you wont immediately call you friend and ask them wtf is wrong with their husband?”

Not if Kailai and Heywood, Neil Heywood were bonking.

Didn’t know Heywood and can’t say I know anyone who knew him, but we do all know chancers who turned up in the 1990′s and earlier who got into positions of influence out of proportion to their actual ability. If the version of Heywood we see here (a Walter Mitty-ish figure trading on his passport) is genuine, then it is entirely believable that he was the kind of person described here.

However, there’s still a lot that makes no sense:

1) How did Heywood get millions into debt? School fees don’t explain it. A failed business might, but we don’t see how here.

2) People don’t ordinarily murder fools who try to shake them down for cash. Was Heywood trying to blackmail Gu? With what? An affair?

The Sunday Times story makes it look like the Bo family got involved with the bumbling, aggressive Heywood out of naivety, and went on to tolerate him until he pushed it too far.

Also, it suggests that Wang Lijun (who has pretty unanimously been painted as a master detective) was completely fooled by Heywood’s antics.

Not saying Heywood wasn’t an idiot. Everyone knows a wannabe Heywood. But is it possible that the Sunday Times’s anonymous source is trying subtly to make the Bo family look slightly less culpable?