You know that sound Skype makes, right? Boo-bee-boo-be-boo. Boo-bee-boo-be-boo.

“Hey dad. What’s up?”

“Not much. Where are you?”

“Back in Beijing.”

“There’s a letter here from Barclay’s.”

“Oh yeah? A statement?”

“Hold on… Dear Mr. Abrahamian, we regret to inform you that your account is being terminated…”

“What?! Why?”

“It doesn’t say. It says to call.”

~

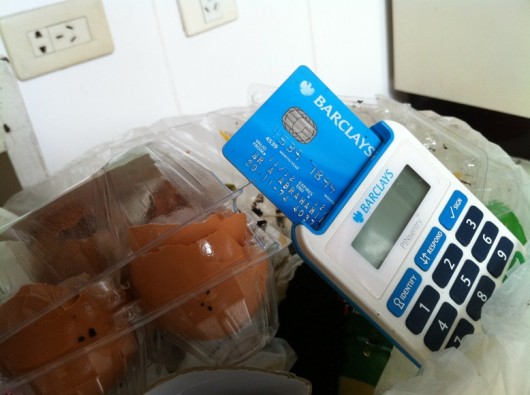

Is it weird to have an emotional attachment to a bank account? Opening it 20 years ago was part of my initiation into adulthood. I may have had an undercut, cherry red Doc Martens, and a signature as fluid as a cave painting, but I was passing some sort of rite with my Barclays account. I could draw money from machines all across the country! There was something to put in the card section of my wallet, other than my library card!

Even as Barclays engaged in criminal behavior, I thought this surely wasn’t a reflection on the lovely old ladies (they were probably only 40) who gave me my first traveler’s cheques or accepted my deposits from my first job in the years that followed.

So when I find out from my father, 10,000 kilometers away, that my account has been cancelled, it’s a bit of a shock.

I ring them up and ask what’s going on, though I’m sure I already know.

“OK sir, I’ll just need to take you through some security questions.”

“No problem.” I rattle off the answers – mother’s maiden name, postcode, address. All the same for basically my whole life. Email address? I pause and give the one I think Barclays wants. I have four or five.

“I’m sorry, but you have failed security,” the woman on the other line monotones.

“Wait, it’s the email address, it must be this other one.”

“I’m sorry, but you have failed security,” she monotones. “I cannot discuss this account with you further. You have to go to your nearest branch with two pieces of I.D.”

“Wait, wait, all that information has been the same my whole life, except…”

“I’m sorry, I cannot discuss this account with you further.”

“I’m living in Beijing!” I yell, the pitch of my voice winding up a bit too high. “Where’s my nearest branch?”

“You’ll have to wait until you come back to the UK.”

“Listen, my account is being closed and I need to know what’s going on,” I plead, my own desperation disgusting me a little.

“I won’t tell you again, sir. I cannot discuss this account with you further.”

The condescension in her words breaks something in me. I’ve always prided myself in never getting angry at customer service people over the phone — whatever problem you’re trying to resolve, it isn’t their fault; they’re just doing a job, and not a fun one at that.

That said:

“Fuck this criminal LIBOR-fixing bank!” I yell. “I don’t want to be a part of it!”

I hang up.

It’s a terrible thing to be led around phone menus by a robot, divorcing you from basic human interaction or understanding, but it is far worse when you have a real person on the line for a change, only to find the robots have assimilated them. Resistance may actually be futile.

Despite what she’s told me, I call back a few moments later. I give the other email address, it works, the pleasant lady says, “Oh, you’ve just called.”

Um… yup.

She tells me that unfortunately, after a review, I no longer meet the criteria to have an account at Barclays.

“What are those criteria?” I ask.

“That’s confidential.”

Of course it is. I thank her politely, begin looking forward to joining a Credit Union or whatever it is hippies recommend these days.

I’m not too upset about Barclays’s robot lady stonewalling my inquiry. I already know what happened.

~

It’s because I work for Choson Exchange, a non-profit based in Singapore. We provide training to young North Korean professionals in business, economic policy, and law. We take foreign experts up to Pyongyang for workshops and also bring North Koreans down to Singapore for study trips and internships. We are of the opinion that the more the next generation of North Koreans are exposed to international norms and standards, the better off we will all be in the long run.

North Korea is, of course, under sanctions. The Koreans sometimes like to use the word “embargo,” though that is false. It’s a targeted sanctions regime, with certain products and specific banks and companies on a list.

Educational exchanges are not on that list.

Moreover, Choson Exchange has never conducted a transaction with a North Korean bank. The only money we’ve ever moved in and out of North Korea has been the minimal amounts of cash we take to pay for accommodation, meals, van rental, and other costs when we run our programs. By far the bulk of our operational budget goes to bringing North Koreans out to Singapore.

Two months ago, Choson Exchange tried to pay my salary directly into my Barclays account, and after much hassle the payment was sent back. How did they know who we were? Why were we on their naughty list? I’m not sure, but I called a friend who also works with North Korea, who also had a Barclays account shut down. It made me feel better and confirmed my suspicions. We then spoke to people we knew who work at another bank, who told us it’s probably because our company has “Choson” in it.

“Choson” — or Chosun — is what North Koreans call Korea. Words like “Choson,” “Pyongyang,” “Koryo,” or even “Korea” in a company or organization’s name can apparently get you placed under scrutiny.

Ultimately, through this tale, we can see two of the key effects of sanctions on North Korea.

First, they scare people away. Barclays doesn’t want to take the slightest chance that an account at their bank might be used for anything under sanction. Why go near it? They’ve been in enough trouble recently, they can’t afford another scandal right now. This fear of getting in trouble confronts prospective investors.

Second, sanctions inconvenience. For me, this means opening a new bank account. For North Koreans — even the many engaged in legitimate business — it means moving money around in diplomatic pouches and suitcases, changing company names and paying a premium to smaller, sketchier banks willing to dance around the edges of the rules.

I mean, not that Barclays won’t skirt the rules when it suits them. Last year they agreed to pay $450 million to settle charges of manipulating the LIBOR rate, while criminal charges are going to be filed against several individual employees soon. But they’re too good for my custom.

Andray Abrahamian is Executive Director of Choson Exchange (@chosonexchange), a Singaporean non-profit providing training for North Koreans in business, economic policy, and law. His previous piece for us was Oi! Kim Jong Un! – How Not to Do Journalism in North Korea.

I can’t help but be perturbed by the inconsistent placement of electrical sockets on the wall…

I really don’t think they care, bank of China should have more concern. Lets face it HSBC was found guilty of money laundering for the al Qaeda, and not only escaped prosecution but the money they were find probably didn’t even cover the amount of money they hand laundered for dodgy deals. On the other hand the US are still trying to go after Bank of China for doing deals with Hezbollah and the only thing standing in their way is Israel.

Forget Barclays then and open an basic account with LTSB who are not quite so difficult.

they dont really care about your situation really. might as well blow to get some money and resolve ur issue