Chen Zhifeng is a “self-made” billionaire, founder of the Western Regions Photography Society, and a major force in Xinjiang’s art scene. He is part of a newly minted cohort of Xinjiang capitalists: the Xinjiang 8 (or 9), who have taken advantage of Chinese-Central Asian market development and the post-Reform oil and gas economy. His Wild Horses Corporation brings in an annual income of $700 million selling Chinese-made women’s underwear and TVs in Russia and Kazakhstan.

Yet, unlike some other Xinjiang elites, Chen has reinvested his wealth in Xinjiang. As a trained artist himself, he is renowned for his support of a multiethnic crew of young Xinjiang artists. With his prominently displayed black Hummer standing sentinel in front of his Wild Horse Hotel compound on Karamay Kunming Road just down the street from the Kazakhstan Embassy visa office, Chen has become a Xinjianger’s Xinjianger. Although he was born in Hubei and came to Xinjiang as the result of a military assignment in 1981, Chen has taken on the cultural genealogy of Xinjiang history with a fierce amount bravado and pride.

1. Photography

When it comes to photographic taste, Chen and the photographers he collects find themselves in debt to Henri Cartier-Bresson and the critical realist tradition of documentary and fine-art photography.

That they should cite Cartier-Bresson as an inspiration should come as no surprise: Cartier-Bresson was the first street photographer to chronicle Xinjiang landscapes. During his four-month stint documenting China’s Great Leap Forward in 1958 for Life magazine and other publications, Cartier-Bresson traveled to Xinjiang to capture exotica at the margins of the Leap. Combining influences from Cartier-Bresson with inspirations as diverse as Diane Arbus and Ansel Adams, Chen and the photographers he funds seem to have an affinity for large format cameras; he exhibits his and others’ work in his own galleries.

Chen takes an industrialist’s approach to media production. Unlike other Xinjiang artists who are forced to sit under the censoring gaze of party organs in state education institutions or hustle their images as commodities to exotica-desiring tourists, Chen has bought himself aesthetic sovereignty backed by the snap of new money. As a result, he produces powerful pictorial assemblages (images, media, spaces) which move viewers toward a new “Xinjiang style” of seeing; his images demand the viewer to re-envision the Xinjiang landscape.

While this critical recovery of the landscape does not magically “make up” for its appropriation by people like Chen who come to power in Xinjiang through accumulation by dispossession – as if art could redeem the nightmares of the cultural crisis experienced by minor actors in the Xinjiang drama – “it does suggest that wonder remains available for decency as well as for domination” (Greenblatt 25).

2. Chen’s Xinjiang

In the images above and below, drawn from a recent exhibition funded and hosted by Chen (curated by Chen Chunhua), three emergent themes relative to contemporary Xinjiang landscapes have been addressed. The first two images represent life on paramilitary farm settlements which are mostly populated by first- and second-generation Han pioneers. Chen and many of the Han photographers featured in the exhibit came to Xinjiang to secure the Chinese-USSR border in the 1980s and stayed on after tours of duty. They joined the army of paramilitary agricultural workers (Bingtuan) who had taken over the steppe with tractors and deep-bore wells in the previous decades; since 1949, 8 to 10 million Han Chinese and Sino-Muslims (Huizu) have moved to Xinjiang.

Yet as is witnessed in these images, due to the recent turning of Hu Jintao’s “Open Up the West” campaign toward the integration of Southern Xinjiang through infrastructure and urbanization (and the general emptying of the countryside across China), many of these Northern Xinjiang communal farms are now inhabited by aging farmers, some of whom feel abandoned by the state, their families, and time itself. Today, images of these locations (Untitled #1, top) shows us an old man holding a pet dog – a replacement, perhaps, for absent grandchildren. Mao still haunts the landscape (Untitled #2, above), but he is fading into the concrete, the pinnacle of a pile of garbage. These images show us that despite the rise of the market economy, old conventions and images still remain.

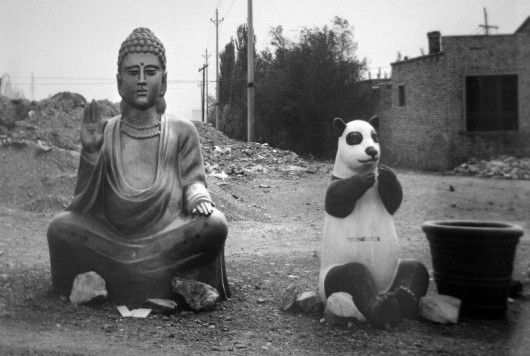

Another theme (Untitled #3 and #4, above) addresses the way the earth responds to current attempts to manufacture a landscape that is both “deeply historical and yet undeniably modern” (Anagnost 1997: 164). The easy critique of these revisionist constructions is that they recreate the “color and flavor” of historically informed culture without simulating a plausible original. Yet as you can see (Untitled #3), a dragon built into the Gobi does in fact simulate the shale from which it rises. It, like the earth, is in the thrall of decay and transformation. In the fourth image, an anemic nationalist panda competes with a meditating Buddha – arm raised as if in protest against the viewer. Behind this line of commoditized cultural symbols the earth erupts in an unregulated mound of garbage just steps from the entrance to the courtyard perimeter of a desolate Western town.

Finally, images above (Untitled #5) and below (Untitled #6) comment on the detritus of commercial tourism and the sale of commoditized culture. Unlike most producers of Xinjiang exotica, Chen Zhifeng is not satisfied to reify the other in timeless landscapes. One of his coterie of photographers set the sharp geometric forms of a Kashgar street in juxtaposition with the silhouette of his large format camera. He and a Uyghur kabob seller stage the shadow of a confrontation by looking right past each other; the endless repetition of misrecognition is therefore amplified, interpolating the viewer as not quite the subject or object of the exchange. We are in a space between; “as subjects, we are literally called into the picture, and represented here as caught” (J. Lacan in Mitchell 2005: xiii).

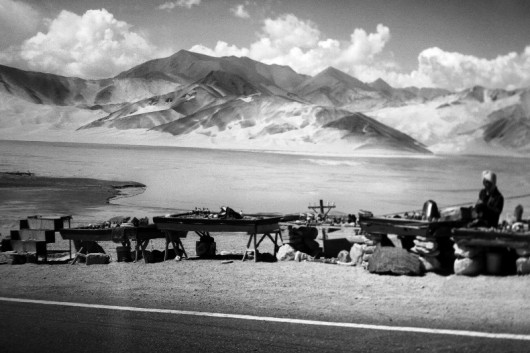

In Untitled #6, shot on a remote road through the Karakorum mountains between Kashgar and Pakistan, a Kyrgyz woman surrounded by “primativist” jewelry spread on repurposed socialist-era billiard tables foregrounds a sweeping vista of a high-elevation salt lake. Yet again the photographer refuses to neatly crop the stranger within a frame of essential difference. A stretch of Chinese road connects the viewer to the object of the gaze, reminding us of the distance between the tourist’s world beside the SUV on the mountainside of the road and that of the nomad capitalist imbricated in the pristine world desired by the landscape-seeking adventurer.

Next week I will discuss Chen Zhifeng’s role as a breeder of blood-sweating horses and curator of Xinjiang artifacts.

Beige Wind runs the website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, which attempts to recognize and create dialogue around the ways minority people create a durable existence, and, in turn, how these voices from the margins implicate all of us in simultaneously distinctive and connected ways.

|Dispatches from Xinjiang Archives|

Further Reading:

Anagnost, A. (1997). National past times: narrative, representation and power in modern China. Duke University Press.

Greenblatt, S. (1991). Marvelous possessions: The wonder of the new world. Oxford University Press, 1991.

Mitchell, W. T. (2005). What do pictures want? The lives and loves of images. University of Chicago Press.

This is boring!

There is no Kazakhstan Embassy anywhere in Urumqi, or Xinjiang for that matter. Fact- checker, check your facts…

Thanks for your close reading Chingis. You’re right it is officially a visa office rather than a dashiguan (embassy), but every Chinese-speaking Kazakhstani and Kazakh friend I know call it a dashiguan. That is also what you tell taxi drivers.

The more important point is that it is not on Karamay Road but on Kunming Road at 216 Kunming Rd Xinshi, Urumqi, Xinjiang China, 830011. It is literally 50 meters from Chen Zhifeng’s Hummer.