“Actually, I think the films themselves are never the issue – the issue is that we call it an ‘independent film festival,’ and the name itself sounds sensitive to them.” –Dong Bingfeng

After a handful of English-language publications declared that authorities had “shut down” the Beijing Independent Film Festival (BIFF), many people likely dusted their hands of the matter, thinking censorship had once again triumphed over artistic expression. But as James Hsu discovered more than a week after the festival’s supposed cancellation, BIFF held a successful, albeit quiet, closing ceremony following a full program of screenings and panels.

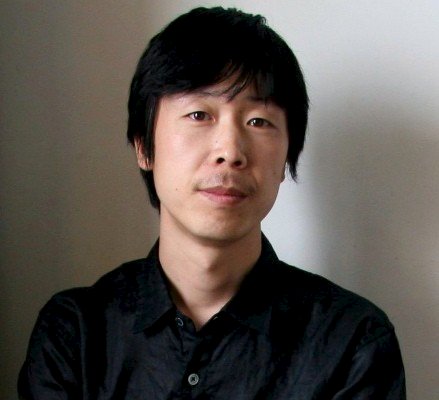

So what happened? A few days after the closing, I met with artistic director Dong Bingfeng to ask him about that and other issues on censorship, film in China, and independent festivals in the future. Among the highlights:

On BIFF’s quick resumption: “If someone says you can’t, then you’ll ask, can you really not? If no one says you can’t, and they’re also at the festival, then no problem…. We found that the second day was okay, and no one came to tell us otherwise.”

On why the government is afraid of independent film: “From 1949 until now, films have remained the most dangerous thing.”

On BIFF’s goals: “I don’t think we are trying to be anti-anything, we’re just trying to find a better way to express ourselves.”

On whether BIFF is political… “The reality of China being what it is, if you’re doing anything creative, whether you’re a writer or a film director or whatever, you can’t avoid being political.”

…or even legal: “Before, we tried to cooperate with the authorities… for example we tried cooperating with a government department or with art museums, but in reality there’s no way we could do it. No way. Because under the Chinese screening system, a film foundation and festival like ours can’t be official because it’s illegal.”

On whether Western media may have jumped the gun in pronouncing BIFF’s demise… “They each have their own views, we’re not going to come and tell them that they have to write this.”

…and their potential biases: “Different countries’ journalists are all different, they’re all interested in specific things; for example, American journalists want to hear about the political aspect of it.”

And on censorship: “I think they just haven’t figured out what to do. Everything is changing – society is changing, the Internet is continuing to develop incredibly quickly, so it’s difficult for the government to control things. And they don’t have an actual policy to stop you from doing it, so all they can do is just shut you down secretly.”

The full interview is below.

How many people ended up coming to the festival?

There were a lot; we had a lot of evaluators, as well as scholars and graduate students from universities overseas, like NYU, King’s College in London, students from Japan and Taiwan. Every year we have people from all different places who are interested in Chinese film.

So the festival wasn’t completely shut down?

No – just the opening ceremony on the first day. But a day later, everything went on as normal.

After the first day, anyone could show – not just official guests?

Yeah.

So actually, the authorities didn’t have a huge impact on the festival?

Well, there wasn’t that big of an audience, but all of the directors and special guests and students knew that the festival was going on, because they were all staying right near the location. So there weren’t a lot of people who didn’t already have a relationship to the festival that made it out on their own.

But it was reported in the media that when the authorities came and shut down the festival, they mandated that there were to be no public screenings, and that if viewed, no more than five people could watch at a time…

No, no, no. That was never the case.

But they said that on the first day, right?

That was on the first day, when there were a lot of police watching us. But as of the second day, they just didn’t have time to come check in on us. So we were able to continue, just not in a very public place. We held the screenings inside our own buildings, we have two screening halls.

You just couldn’t advertise?

Right.

Could you describe what happened on the first day? Did you expect something like this to happen?

Last year was our ninth festival, and it got shut down during a public viewing. That year we had four or five underground festivals that were supposed to be held across the country, in places like Kunming, Nanjing, Chongqing, so all of them got shut down. So based on what happened last year, we knew we would almost definitely run into problems this year, and were prepared for it.

For our opening ceremony, in addition to choosing a public location, we also had a backup location at our offices. But at the opening, there were a lot of plainclothes police who were taking pictures and recording, and they told us right then that we were not to show any films…. The entire first day, from afternoon till evening, we weren’t able to show any movies or do any of the programming at all. They were very clear about that – that we were not to do any screenings.

But then, starting on the second day, things were looking okay. So since we had so much media and so many guests who came on the first day expecting to see films, we gave out DVDs – it wasn’t all the films, maybe two-thirds of them – for them to take home and watch. But starting from the second day, the programming went on as scheduled.

When the police came, did you already have an inkling that you’d be able to go on the second day as scheduled?

No, we didn’t know. They told us on the first day that we were not to do any screenings, so there was no way for us to tell the people there whether or not we would be able to continue the next day. But then we found that the second day was okay, and no one came to tell us otherwise.

You guys weren’t worried?

I didn’t think it was a problem. Because whether or not they allowed us to do the screenings, for me, wasn’t the most important thing, because we could always show the movies in smaller places, like studios or hotels or wherever.

It was reported that if you went on with the festival, the festival’s director, Wang Hongwei, would be arrested. You weren’t worried about that?

It wasn’t that we weren’t worried about it – but… if on the first day there are police telling you that you can’t do any screening events, then we will definitely comply, because nobody wants the conflict to escalate. (Just like last year, when we had a really serious conflict, which helped us prepare for this year.) But then the next day, no one came to tell us that we couldn’t carry on, so it was a very different circumstance. If someone says you can’t, then you’ll ask, can you really not? If no one says you can’t, and they’re also at the festival, then no problem.

When you ran into these problems on the first day, how did the directors and judges and special guests respond?

Because all of us, including the organizers, didn’t know what was going to happen the next day — we totally didn’t know if we could or couldn’t go on, what we could do, what we couldn’t do — everybody on the first day just waited. So of course we couldn’t tell the special guests and directors that we’d be able to go on the next day. But since we had already booked all the hotels for the participants, they went and checked in that night, so we knew that if we had news the next day, we’d be able to tell everyone right away. But if you were press or audience that had come in from Beijing, then we had no way to tell you whether or not the festival was going to go on the next day. So that was a really big difference.

As I’m sure you noticed, there were a lot of reports about the shutdown. Were you tempted to contact the press and let them know that the festival was actually going on?

My own feeling is that we are completely open with the media, because they were either there on the opening day or they called to ask what was going on. Now, of course, on the first day, everything was really muddled – we were just waiting, and didn’t know yet whether or not we’d be able to continue. So some of the media simply wrote stories based on that angle, or some of them asked us for updated news. But every reporter is going to have their own angle, or specific issues that they want to focus on, so we’re not going to go and correct their reports. Because they each have their own views, we’re not going to come and tell them that they have to write this.

In terms of getting media the updated information – I mean, this is China, and this is a really underground film festival, so anything could happen, anything could change at a moment’s notice. I think that’s pretty standard here and to be expected.

Did any media report that the festival would go on?

There was one foreign website called Art Info that reported it. Also, the Wall Street Journal came out with a pretty accurate report.

How long did it take to plan this year’s festival, and how much money did you spend?

It takes a year to plan. So for instance, this year’s festival just finished; next week we’ll start planning next year’s. Last year we spent around 300,000 RMB. This year we probably spent a little less on normal costs, because the audience was smaller, so the scale was a bit smaller. But this year, because we were able to do normal screenings, we built a new screening room. That alone cost 300,000, so altogether it was probably around 500,000 RMB.

Where does your money come from?

There are a lot of artists who support us; this year, that’s where most of our money came from, Chinese artists and some individual donors.

In terms of subject matter or themes, what kinds of films does the festival usually go for?

Since people already know the direction we’re going with this festival, we don’t get a lot of commercial films, or establishment films, or films that are overly pedantic. Most of the films that we end up with are extremely underground – it might be made by a writer, or painter, or just a normal farmer from the countryside. This year we have a farmer, a 62-year-old farmer from the countryside, who shot a documentary. He just took a camera and went to his village and shot everything that happened to him. So looking at it as a whole, I would say that the festival focuses on society and social issues. We’re interested in taking some of these social questions, even including some political questions, and including them in the creation of these films and the thought process that goes along with them. This is of course very different from the bigger film festivals you see in Beijing or Shanghai, and that’s one of our goals.

Do you think BIFF has a social or political goal?

I think that the reality of China being what it is, if you’re doing anything creative, whether you’re a writer or a film director or whatever, you can’t avoid being political. It’s everywhere – everything we talk about every day is political, so today seems like a more sensitive time than any other, more direct.

Do you prefer movies with a social bent, or do you just choose them based on quality?

I think it’s probably about half and half. Half of it depends on our own motivations and expectations, and the other half on the judges and the competition. In terms of which movies we screen, in the end we have to return to the film itself, and we’re looking at the quality of it, the aesthetic of it. So as a whole, I wouldn’t say we have a very strictly political atmosphere to the festival or the way we choose films, but we are very different from mainstream film festivals.

You guys are an underground film festival, which means you’ll naturally attract the attention of the authorities. Have you ever considered choosing less controversial films to allow the festival to go forward?

No. Before, we tried to cooperate with the authorities… for example we tried cooperating with a government department or with art museums, but in reality there’s no way we could do it. No way. Because under the Chinese screening system, a film foundation and festival like ours can’t be official because it’s illegal. So now we’re trying to change the situation – like, we set up different sections for the festival. There’s the screening section, the panel section and the publication section – every year we publish some books and magazines – so among these sections, the panel discussions and the publication parts are completely legal. We use big galleries to hold the panels, like we did at UCCA. So we use these two sections to get more attention.

In the end, it’s also a learning experience for us; I don’t think we are trying to be anti-anything, we’re just trying to find a better way to express ourselves, so we have to make choices. I hope people see our work, and are able to see the festival in a general way.

This is related to my next question, which is that I’ve heard some people say that the reason BIFF got shut down is because you refused to submit the films ahead of time for government approval. Is that true?

No, actually we did submit the films ahead of time – we always do this, because you have to, you can’t refuse them. Like one day, the cops in Xongzhuang came to ask what movies we were going to be screening, so we gave them the list and all the DVDs for them to watch. Because really it didn’t matter – only a very few movies are seriously hardcore political stuff, like Ai Weiwei’s documentary. There are very few films like that, so I didn’t think they would affect the festival as a whole. And actually, I think the films themselves are never the issue – the issue is that we call it an “independent film festival,” and the name itself sounds sensitive to them.

If you let them check out the films ahead of time, why is it still illegal?

Because they couldn’t make a decision about them; it’s a pretty complicated system. Censorship itself has leaks. They may say a piece of video art doesn’t seem right, that it’s illegal, but then what about all of the weird, experimental artsy stuff screening inside galleries as a part of contemporary art? So it’s hard for them to judge. But what they do know is that being “underground” is extremely sensitive, so with ambiguous things like this, they don’t want to take the risk.

So if you want to avoid things like this, you have to find an official partner to collaborate with, like the UCCA?

Yeah, sort of. Basically, the government doesn’t care and isn’t even going to pay attention to what filmsyou’re going to screen. They don’t understand the films themselves, which is why we think they don’t have a legitimate reason to shut it down. This year, the festival has five or six parts, with nine venues all over China. Shenzhen and Tianjin both haven’t had any problems, and we’ll start soon in those two cities. In Beijing, there are at least two galleries that were hosting parts of the festival – UCCA and Yuan Dian Gallery. They shut down the events at those locations on the first day as well.

One thing I find interesting is that other art forms don’t seem to have these kinds of problems – like every year there are underground music festivals, punk festivals, that go on without any problems. So why are things so hard for the indie film community?

I think in China, out of all the art forms – writing, music, art, what have you – film is the most dangerous by far. In all socialist countries, like Iran for instance, a lot of directors are in jail. China too. A director like Ying Liang, he can’t come back to China; he can only stay in Hong Kong. Ai Weiwei as well. (Ed’s note: he’s not allowed to leave China.) So in any country where there’s a tense political situation, the government is on edge that films can affect a lot of people, even people who don’t know how to read or write. So in that sense, indie films have a lot of potential for danger, beyond all other kinds of art.

From 1949 until now, films have remained the most dangerous thing. You see Hollywood films that are screened here, and parts of them are cut off. Or a band like Metallica comes to play in Shanghai, and their lyrics need to be approved first…

But if the government knows that the only people who are really involved in the festival are underground filmmakers and art world people, and it won’t really have a chance to reach the mainstream, what are they so afraid of?

I think they just haven’t figured out what to do. Everything is changing – society is changing, the Internet is continuing to develop incredibly quickly, so it’s difficult for the government to control things. And they don’t have an actual policy to stop you from doing it, so all they can do is just shut you down secretly.

Why didn’t authorities come on any of the subsequent days to make sure that was enforced?

Because the first day we opened the festival in an open space and did some promotion, so it was more official. The subsequent days we moved to a more private space – actually held it as a kind of underground event – so I think they were okay with that, as long as we kept it on the down0low. So it’s been changing… we’ve been negotiating with them, and for them, if we keep it low-key, it’s not that big of a deal.

The police came on the final day and were recording, but didn’t actually do anything, right?

Yeah. I think for a lot of artists, what they want to address is the current reality, which is inherently political. I think the government just needs to find an appropriate way to deal with it, instead of just using police force to intervene. From 1991 up till now, Chinese indie movies have documented various sides of society and various realities. So I think what we have now is a really good archive. We hope that we can continue to use those sources through the festival to affect more young people and build their interest in indie films and social issues.

What’s your plan for next year?

I think in China, you never know what’s going to happen tomorrow, it’s always an unknown. So we can’t really prepare for anything. This year, a lot of film festivals in China were shut down, but we’ll see – in November, there’s a film festival in Nanjing; if that can happen, maybe it means that the government is starting to loosen control and take it easy. We’ll see.

There were a lot of reports in the Western media that played up the initial shutdown in what some would call a sensationalistic way, considering the ultimate continuation of the festival. What do you think of those reports?

I don’t refuse any of them; I think everyone has the right to write down what they saw and what they feel about it. Like, the audience came to our festival and had their own experience, and we’re open to that. I wouldn’t tell anyone what they should write. Different countries’ journalists are all different, they’re all interested in specific things; for example, American journalists want to hear about the political aspect of it. Actually, we’re working on a documentary about the media: we want to show people the same issue from many different angles, because it’s that as a whole that shows the truth.

Everyone has their own story that they want to tell.

Right. And films are all about stories.

Liz Tung is an associate editor at Time Out Beijing.