This is a follow-up to last month’s piece on Liu Xiaodong at the first Xinjiang Biennale in 2012.

A lot of people turned out for the final day of the Xinjiang Art Biennale on July 20 at the International Expo Center. The massive complex, situated next to a giant Buddha and Hilton Hotel in the city’s northeast, echoed with the sounds of an original score by Philip Glass called “Encounter on the Silk Road.” Indeed, exhibition was heavy on spectacle. Giant video screens, paintings, and sculptures drew the largely Han crowd into massive spaces lit by natural light. Smartphone cameras were often raised at the mesmerizing objects, which called the viewer to contemplate Xinjiang as “a land of many colors.”

True to this theme, many of the pieces on display were both diverse and provocative. Although there was a smattering of the usual pantheon of Chinese avant-garde works – and much of the video art seemed to be from Bulgaria and Italy — many of the pieces were specific to the region. As the deputy director of the Xinjiang Ministry of Culture and head curator of the show Zhang Zikang put it, the Biennale is a big step in leading Xinjiangers to embrace art. He estimated more than 300,000 people (close to a tenth of the population of Ürümchi) would see the show over the month that it was on. For Zhang, a former director of Beijing’s Today Art Museum, this is “extremely important” because art carries values that all humans believe in. As he told the Global Times, art “can help create understanding.”

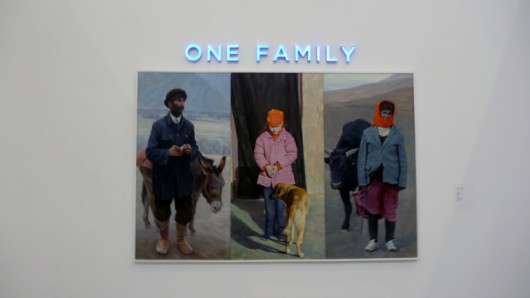

Something on the order of 20 percent of the hundreds of pieces were paintings by minority artists. And a majority of the other works were Xinjiang-specific paintings by Han artists. Although some of these paintings fell into the usual traps of representing the exotic, many were quite sophisticated in their interpretation of local traditions and the life of urban and rural landscapes.

The exhibition overview asked us to consider the ways in which Xinjiang can reach out to the world with openness and innovation. And many of the visitors did just that. They read the painting descriptions with care, they touched the paint, caressed the sculptures, and posed as participants in the paintings. They tried to understand, but sometimes they spoke to the painters – saying stuff like “A-ni-wa-er, I see but don’t understand.”

Part of this frustration came from the way many of the paintings from minority artists like Enwer, Nurmemet Alimehman, Kamil Abdushakir, and Qurbandi focused on abstract feelings such as “noise,” “memory,” and “invisibility.” Another Uyghur artist named Ali K. depicted the subtleties of life among trash by imposing paintings of animals on large-scale pictures of garbage, which was perplexing to some viewers who said in the Northwest-style, “Sa yisi?” or “What does it mean?” My sense is that the artists were not trying to frustrate the viewer as much as comment indirectly on their experience of contemporary life.

Wind and Rain in Sanlitun Village | Enwer

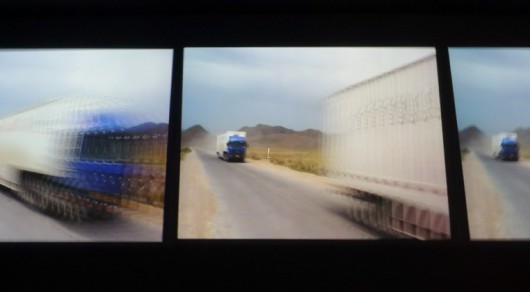

Many Han painters focused on life in the countryside, where the Bingtuan apparatus is crumbling; they showed us the power of Xinjiang’s ecosystem. But a display by the Kyrgyzstani video artists Muratbek Djumaliev and Gulnara Kasmalieva demonstrated some of the more important changes underway. Their short intersecting videos called “The New Silk Road” shows us the breakdown of Soviet-era trucks as they haul loads of recyclable steel toward the viewer, and then are gradually replaced by the arrival of Chinese trucks. They just keep coming and coming and coming and coming. The piece is magnificent and active in the pain of change, which is now fully on the Eastern horizon for the Central Asian Republics.

The Silk Road | Muratbek Djumaliev and Gulnara Kasmalieva

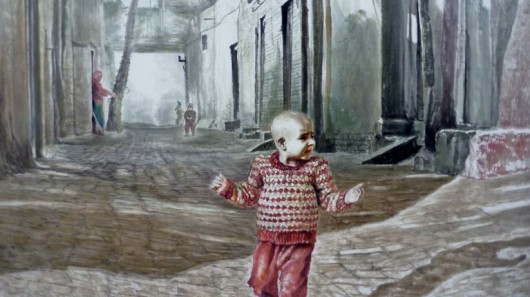

Others, such as Tian Fu, depicted vanishing streetlife in Kashgar with a painting called “Sunshine and I.” The painting, one of the most poignant in the show, is a portrait of a young Uyghur boy, his head freshly shaved in order to ensure that he will have a strong crop of hair, as he plays on a neighborhood street.

Many of the paintings were from a series by young artists selected by the culture ministry from Eastern institutions. They are plainly beautiful. They show us what a Uyghur face looks like when rendered in the style of a European Old Master. Or they show us moments of life, where a turn of the head, the settling dusk on a herd of sheep, becomes something more. The Biennale shows us flashes of life itself.

Looking for Grazing in Suwu | Li Huaqi

Beige Wind runs the website The Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, which attempts to recognize and create dialogue around the ways minority people create a durable existence, and, in turn, how these voices from the margins implicate all of us in simultaneously distinctive and connected ways.