By Jim Fields

New arrivals to Beijing often revel in the sheer chaos of the city. Cars, bikes, and motorized tricycles compete for inches of pavement (sometimes resulting in ungodly traffic jams). Children drop trou and relieve themselves among dining patrons at restaurants. And, of course, as any foreigner in China will tell you, there are no open container laws – hence, you can walk down the road with a Tsingtao in one hand*, yangrou chuan’r in the other without fear of the 5-0 rolling up and putting you in the drunk tank. This apparent chaos might lead a new arrival to believe that there is a complete lack of rules and ordinances whatsoever.

However, as you spend more time in China, you begin to realize – ordinances are everywhere, even where you least expect.

Don’t walk on the grass. Don’t smoke in the bathroom. Don’t set up a webcam in your home to surveil yourself. What’s a guy to do?

The answer, of course, is to become extremely selective in deciding which ordinances to follow – a process that resembles reading tea leaves: equal parts attention to detail, feigned experience, and an ability to improvise under pressure. Realizing this simple fact took me an embarrassing amount of time. I would whine to my friends, sputtering, “But pedestrians have the right of way, not cars!” … “Doesn’t that man know he shouldn’t be rolling a cigarette while riding his bike and talking on his cell phone?”… “Shouldn’t these migrant workers and their huge canvas bags allow me to get off the subway before they try to get on?” My friends soon grew tired of my personal crusade.

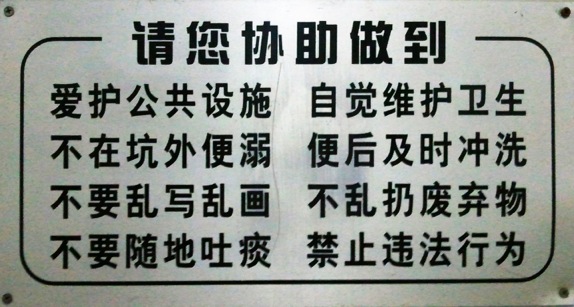

The odd beauty of many ordinances in China is that they all seem to be written from the perspective of an eternally wise yet distinctly paternal figure. They are very unlike ordinances in the US, filled with legalese, threats of fines, and lawsuit-proof doubletalk. Written Chinese ordinances feel more like instructions to a child, penned by a nationalistic, oddly anatomically-obsessed uncle. For example, here’s a sign that’s hung inside a public bathroom in Beijing’s Dongcheng District:

Please aid us in:

- Cherishing public facilities

- Not peeing outside the toilet bowl

- Not writing graffiti on the walls

- Not spitting on the ground at will

- Conscientiously defending hygiene

- After relieving yourself, promptly flushing

- Not indiscriminately discarding garbage

- Prohibiting illegal behavior

So there you have it. When you read the first item – “cherishing public facilities” – you’re left wondering, “By writing a poem, perhaps?” When we reach #2 on the list, we learn the answer: by not peeing outside of the toilet bowl. Of course. Why didn’t you think of that?

The rest of the list makes clear in excruciating detail exactly how you should behave whilst relieving yourself. Obviously, as any visitor to a Chinese public restroom can tell you, these rules are rarely followed – you can imagine my surprise the first time I found these rules being blatantly flouted (I would provide links to examples, but my first Google Image search opened up a Pandora’s box of unspeakable horrors).

It’s a shame they didn’t post signs about “prohibiting illegal behavior” in Qingdao, where government funds were spent to provide toilet paper that was almost immediately stolen in bulk. That’s not conscientiously defending hygiene at all.

–

* You don’t even need a paper bag!

Follow Jim @jimfields.

For the sign inside a bathroom, you got the sequence wrong. #1 should be followed by #5, the correct sequence should be 1,5,2,6,3,7,4,8.

Top to bottom, left to right. The translations and their ordering are just fine.