Boarding an airplane can put you through the rawest five minutes of judgement you’ll ever face, especially if you’re a foreigner. Like a slow, awkward fashion show, you amble down the aisle in fits and starts while everyone already seated simply stare.

On my recent Guilin-bound Chengdu plane, I was generally spared of any finger-pointing or comments before I slid into my middle seat, wedged between A and C.

But then the 20-year-old boys came.

A hoard of these young men, jostling down the aisle in search for their seats, froze when they arrived at my row. I don’t speak Sichuanese, but by now I have a keen enough sense of when people are talking about me that I understood what was so funny.

“Oh, I have to sit with a foreigner!” one boy guffawed, and his friends pushed him toward his seat (Seat A, next to the window). “Switch with me!” he begged his friends. “No, no, you have to sit there!” they replied, and he edged in and buckled up.

I’ve never been one to 忍 (suffer silently, something the Chinese consider to be a virtue), so I turned to him and asked, “What’s wrong? Don’t like foreigners?”

“Huh?”

“I said, what’s your problem with foreigners?”

“Oh, you speak Chinese?”

“Yes…” By now the surrounding seats were silent. Those in the row in front practically had their ears pressed to the gap between the cushions. “So why don’t you want to sit next to a foreigner?”

“It’s not that, it’s just that… do you mind switching with my friend?”

His friend had been standing and watching, so I took the ticket out of his hand. Getting my baggage out of the overhead bin, I said sharply, “Don’t talk about foreigners like that.” Then I moved to the back of the plane.

~

I first came to China on a CET program in 2008. Teachers regarded my initial disgust with everything as culture shock. Within a month I got over — and even came to appreciate and enjoy — China’s dirtiness, its chaos, its underlying freestyle beat. One thing I could never come to terms with, however, was being made to feel like an outsider: the staring, the pointing, locals wanting to take pictures with you, and the never-ending line of inquiry, “You foreigners all like ___, right?”

“It’s just different,” my classmates would say, implying that I was simply intolerant.

“They don’t know any better,” they would add, absolving the finger-pointers and gawkers of responsibility.

“You have to understand their point of view.”

I was confused about how racism should be forgivable once you’re the target of it. But when you’re in love with China, as I increasingly was in those salad days of underground music and hutong prowling, what can you do? You take the good with the bad. I learned to shut my mouth and let the fingers point. I smiled in the tourist photos. I wrote a study abroad essay about how I learned to get along with Chinese people, and won $100.

Two years in Chinese grad school and two Chinese boyfriends later, I wised up. In tolerating ostracization, I had allowed Chinese friends and acquaintances to walk all over me, assign an identity to me, basically overlook everything about me to satisfy their expectations as someone they could understand. As the only person from my study abroad class to have become fluent in Chinese and still be here, I decided to rethink the mantra, “It’s just different.”

There is certainly value in recognizing that cultures have different standards, and to evaluate other people’s actions in respect to their intent. But to look the other way when racism is happening and write it off as a “cultural difference” is putting on a muzzle, a form of self-censorship.

For sure, I have real Chinese friends, as I’ve previously written about. They have the self-awareness to not make me feel like an outsider, and don’t care that we’re different. They are not like my many other Chinese acquaintances who speak to me slowly and applaud my ability to use chopsticks. While I recognize they think they’re being helpful, these aren’t the people I choose to spend time with.

Two summers ago in Beijing, I prowled down a Gulou hutong with two Chinese friends and an American classmate — a posse that had been forged over Tsingtao beers and shaokao and open mic nights. “It’s American Independence Day,” said Haozi, “so I have a question for you. When are you going to free China?”

I paused a second and then burst out laughing. Irony and humor are easily lost across cultures and languages. Unfazed, Haozi gave his two American friends a chance to join in the joke. He’ll never know how much I appreciated that.

~

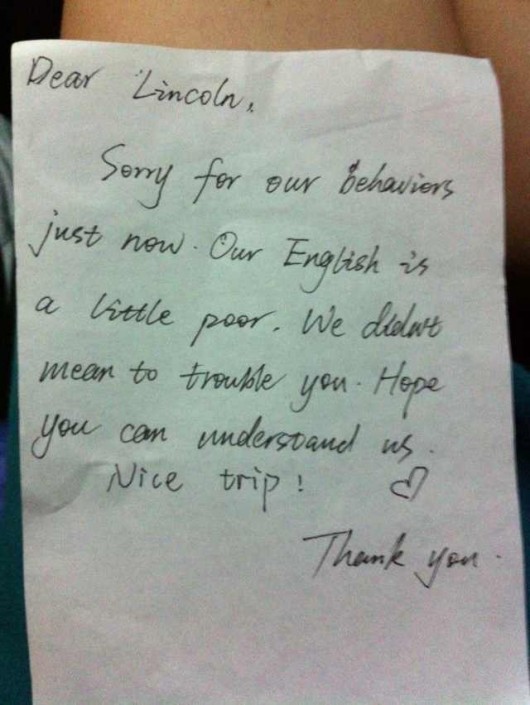

Ten minutes later, sitting near the back of Flight CA 3241 from Chengdu to Guilin, a stewardess brought me a handwritten note.

Dear Lincoln,

Sorry for our behaviors just now. Our English is a little poor. We didn’t mean to trouble you. Hope you can understand us.

Nice trip! <3

Thank you.

It looks like the boys got my last name off the ticket, but apparently over-thought the first name/last name thing.

I admit, I hadn’t really been angry with them — the questioning was partly for show. They were, after all, just boys horsing around, maybe on their first vacation without their parents. But hopefully, because I spoke up, they came away with an understanding that foreigners are not so foreign.

And I found myself endeared by their follow-up act, and affirmed in my belief that living in this country long-term is worth the effort. I am constantly still learning – among other things, about how you must recognize when to draw the line between being culturally sensitive and sticking to your principles. Stick with it long enough and this country has a way of rewarding you with surprises that you didn’t realize or had forgotten were possible. You’ll absorb lessons that you just can’t pick up from a semester abroad. Hope you can understand.

More from Hannah Lincoln: a tour of the world’s largest building.

Thank you for sharing your story, I do agree with many things, maybe I’ve been in China less time than you, but I really understand your points, sometimes I feel I’m going to freak out because it’s like they are trying to make you not to forget “you are a foreigner”, being an outsider in a collective society it’s not an easy thing, but I’ve learned a lot of things and I feel happy for that. I loved this “You’ll absorb lessons that you just can’t pick up from a semester abroad.” 好好照顾自己!

This was my experience living in China.. pretty much daily. The locals are F’d in the head if they ‘assume you don’t speak Chinese’. You ail constantly be told BS about how ‘You don’t understand’ or you misunderstand the culture and bla bla bla.

But when your Mandarin ( for example) gets so good that you can understand everything going on around you, you will probably lose your mind, hearing the most inane BS on a daily basis. Hearing people talking about foreigners, because you were spotted on the bus, is just F’n infuriating. This happened all the time in BJ/SH.

This letter is utter horseshit. Their ‘English was poor’? No, their was pretty clear and they were spouting ignorant gibberish about a random white guy, like rednecks. This is the norm for young Chinese men. Pure hormones + nationalism I guess.

How do you think minorities in the US feel ALL OF THE FUCKING TIME? The answer is the same way you did for 10 minutes in an airplane (yes, an airplane– a LUXURY form of transportation) or for 15 seconds in a convenience store while people looked goggle-eyed at you while you searched for change in your pockets or whatever. Imagine feeling that way every time you went out in public for your entire life, imagine also never having the chance to travel abroad and thus never having the chance to complain publicly about what a fucking task it was to be a privileged, overly-sensitive Westerner in a developing country where people just couldn’t “understand” you. Because apparently when you travel abroad it’s everyone else’s job to understand where you’re coming from (!?). This article has white privilege written all over it. Next time you feel this way instead of contemplating how good it’s going to feel to rant about the narrow-mindedness of the Chinese to your fellow foreign classmates over beer and chuar, bite your tongue and think about how non-whites the world over feel every time they step out of their house or their neighborhood and into the so-called “color-blind” space the white people who own it call “public.” Then you’ll have learned something from your time abroad.

To echo Chris’ remarks, I find it somewhat petty that a white American (whose countrymen forced China to open up to immigration with gunboats during the Opium Wars) complain about being treated like an outsider in China.

Moreover, I think that this does reflect something about white privilege: white people (and I include myself in saying this) often don’t realize just how profoundly race inserts itself into one’s own daily life. If I feel uncomfortable at times in China because I’m the only white person in the room, and as such am attracting attention, I have to remind myself that this is only a very small taste of what non-white Americans often experience in nearly every aspect of their daily lives.

Truthfully, being a foreigner in China can be awkward. At times, one feels much like the writer does, like they are noticeably different… because we are. As a white person living in this country, I AM noticeably different from the Chinese people I live around, even those who live in Beijing (where ethnic and racial diversity are somewhat more common), let alone second tier cities like Guilin. I’m not Chinese. To expect that I would be treated as if I were is not realistic. To be offended because the wait-staff at a restaurant hands me a picture menu even though I can speak (and read) decent Chinese; because children in a third tier city who’ve never seen a non-Chinese person in their lives ask to take a picture with me; because a young guy from Sichuan assumes he won’t be able to communicate with you and thus feels awkward about sitting next to you on an airplane; because well-meaning Chinese have the courtesy to speak intelligibly to you rather than speaking to you like a native speaker; that seems a little overly-sensistive, a little 过分. True, these things are not something you have to like or accept, but such harmless instances aren’t really worth the blustery response. Feeling so upset about this that one is compelled to write a lengthy, frustrated blog post? Seems like blowing a relatively minor incident WAY out of proportion.

To label “being made to feel like an outsider: the staring, the pointing, locals wanting to take pictures with you” as racism reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of what it means to truly be the target of discriminatory policies or harmful racism.