“Mr. Kim Jong Un! Channel 4 News, UK!” yelled the journalist at the back of Kim Jong Un’s head.

The Great Marshall stopped. He slowly turned and smiled, his visage a million shining suns. The room, which had been full of raucous cheers, came to a hush. In perfect English he replied, “Yes? How may I help you?”

Just kidding. That last part didn’t happen.

~

Visiting Pyongyang always has an element of surreality. The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea is just such a different way of organizing a society, the last such social experiment of this sort, stubbornly hanging on in contravention of all predictions.

But when visiting, especially for the first time, many things are far more normal than you would expect (which is strange in and of itself), and some things can appear even more depressing. How you process what you see and encounter depends on who you are.

If who you are is a journalist, North Korea basically represents the hardest reporting target in the world. If you’re writing from the outside, you have to plow through acres of rumor and guesswork to try to assess what’s happening. It’s difficult to get into North Korea as a journalist, and if you are accepted, you end up on heavily-managed tours or junkets. If you sneak in on a tourist visa, you generally get to reveal nothing special (thousands of Western tourists go every year), and moreover, you probably harm the interests of whatever company or organization invited you. Take, for example, John Sweeney of the BBC. He snuck in on a London School of Economics trip and made the most unrevealing, contrived hack job of an undercover report you could imagine. Let’s see if LSE gets to bring people in next year.

Certainly, the BBC was absent last week as foreign media were invited to cover the 60th anniversary of the armistice that stopped fighting in the Korean War.

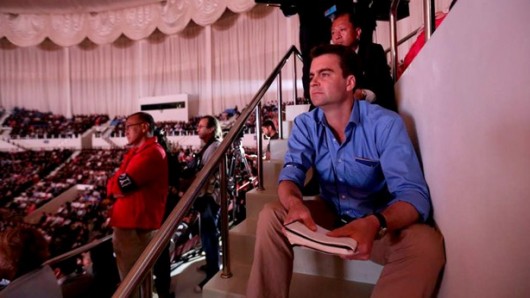

Channel 4 News, however, was there, and it was with its reporter, John Sparks, that I was chatting with in the newly christened war museum one afternoon. They had just finished the opening ceremony, presided over by Kim Jong Un. I thought that because we were allowed to go in so soon after the ceremony meant Kim had already gone out the back. Every other event that week had us arriving long before the man himself, and then we were kept in our seats until he’d left.

But suddenly there was applause and cheers in the hallway next to where we were standing. It could only mean one thing. We quickly darted over, and there he was, with a scrum of people all around, looking frankly quite comfortable with it all. It was such an exciting surprise, it was hard to believe it was happening. Then, at my left shoulder:

“Mr. Kim Jong Un! Channel 4 News, UK! What message are you trying to send to the West?”

To my credit — if I may say so — I turned to Mr. Sparks and asked in that incredulous teenager’s tone: “Really?”

“Well,” he muttered, “if I’d had more time…”

At first I thought I’d made Sparks see the pathetic desperation that characterizes such journalistic “exchanges.” Of course Kim ignored him and moved on, dragging the melee behind him. When I left North Korea, however, I realized that Sparks had actually filed a story titled, Inside North Korea: Channel 4 News questions Kim Jong-un. “Channel 4 News becomes the first news organisation to question leader Kim Jong-un,” reads the subhead. Presumably, “Inside North Korea: Channel 4 News yells at back of Kim Jong-un’s head” was changed by an editor.

Now, I understand that “doorstepping” is an acceptable tool in the modern journalist’s box, even if to me it seems desperate, intrusive, and unilluminating in pretty much all circumstances. (Oooo, look how uncomfortable he looks… must be guilty.) They rarely produce answers, certainly not from sitting heads of state, and certainly not in freaking North Korea*. I mean, Sparks knew he wasn’t going to get an answer.

But looking at his DPRK dispatches, it’s easy to see that actually learning anything about North Korea or attempting some form of illuminating representation was never a part of his agenda.

First, of the encounter, Sparks writes, “He gave me a look but kept on walking.” That is partially true and would have been fully accurate if he had only written, “He kept on walking.”

The video on Channel 4’s site also contains downright disingenuous moments. When describing the military parade, Sparks says, “Not everything was as it seemed. The sound of cheering crowds had been prerecorded, some band members didn’t seem to be playing their instruments, and bits of soldiers’ gear looked suspect, like these plastic-looking grenades.”

Having also been at the parade, I can say that those grenades look fake because they were pinned to the belts of middle school marchers. Channel 4’s shot selection was intentionally misleading. And some band members didn’t appear to be playing their instruments because they played pieces in shifts. It was two hours in the relentless, blazing sun. Have you tried blowing a trumpet for two hours in 33-degree weather with no water? No, you haven’t, because that’s mental. (One musician apparently collapsed afterwards.)

I don’t want to be too hard on John Sparks, though. After all, as the correspondent for all of Asia, he’s got a lot on his plate. As I said, covering North Korea is exceptionally difficult. The problems associated with that country are complex, and TV news is especially poorly suited to covering them. TV is good for explosions and parades, but the conventional sound bites it must trade in just don’t get to the heart of any of North Korea’s problems. It is too easy to just look at the nukes, the weird culture, the failed economy, and call the people zombies or slaves.

(Sparks, by the way, calls his minders “Number 1” and “Number 2,” and writes that after seeing Kim Jong Un brisk by, “They were speechless. I don’t know if it was the fact that I had asked the ‘great marshal’ a question – or because they had found themselves so close to him but they looked stunned.” I talked to other journalists that week who learned their minders’ names and developed good rapport with them — you know, treated them as actual people.)

There are also general professional pressures that make it very hard for news about North Korea to be free of bias. These include a dependence on official sources for information and alignment with the state on foreign affairs, which are exacerbated during wartime. Despite Pyongyang trumpeting their victory (or were they really trumpeting?), the celebrations last week were merely for an armistice. The war, technically — and sometimes kinetically — continues to this day.

North Korea doesn’t help itself by being so secretive. The desire to control all information not only rankles journalists, but creates distortions by forcing a news-hungry world to wade through the muck of rumor and guesswork. This is why we so desperately need more journalists willing to look deeper, do more research, and tell us longer stories with more complicated analyses.

There are a few out there. But don’t go looking for them on Channel 4.

*North Korea nerds: no need to write and tell me Kim Yong Nam is the actual head of state.

Andray Abrahamian is Executive Director of Choson Exchange (@chosonexchange), a Singaporean non-profit providing training for North Koreans in business, economic policy, and law. His PhD dissertation was on Western media coverage of North Korea.

Excellent piece. His minders were undoubtedly aghast and this may not bode well for their careers, to say the least.

Dear Andray, great description of how Western journalists assume that Pyongyang IS NK, how in response to state control of information they clutch at straws, and how they spin ‘news’ out of nothing.

You also point out that they also fail to look for the kind of detail and analysis that might bring actual insight.

For instance, there’s the assumption that all defectors and refugees are the same. But there’s a big difference between a farmer from the provinces who has escaped in search of work or food, and someone like Jang Jin-sung, the grandson of one of the DPRK’s 4 Marshals, the other three being Kim, Kim and Kim.

Every defector has a story to tell and motives in telling it, but Jang speaks with first-hand knowledge of the workings of the regime, of having been a favourite of Kim Jong-il and of having worked in the psychological warfare department’s 1 October building, whose name ironically echoes Orwell’s Room 101. He defected in disgust at the inside knowledge to which his position and job made him privy, but his agenda is transparency, not personal justification or gain.

Journalists might do well to visit to find material from authoritative defectors and from authentic clandestine sources from within the DPRK regime.

All the best,

Martin

Good piece Andray,

This journalist is a common journalist. He wants more for less.

PS: Kim Yong Nam is signing accreditation letters of ambassadors on behalf of Kim Il Sung:)

Nicolas

I think this article is a little unfair considering having already pointed out that Sparks covers the entire continent. Yes doorstepping is crude but when it’s impossible to have any respect for the country or its leader I think anyone would have done it, if only to say they had. It’s humorous and so adds much needed ridicule to an article about this crazy country. It also doesn’t hurt to pull some people in who might otherwise pay no attention in reading it.

While I accept some of what’s said here, when you have to deliver a 5 minute VT about the most insane country on the planet you don’t have anywhere near enough time to delve into the glimpses of humanity that lie beneath the veneer of nonsense that is North Korea. As you say, leave it to those who can.

I also see no problem with identifying your minders by number only. These people are essentially zombies, promoted to the privileged position of minders by their unswerving dedication to the state, whose behaviour is entirely to keep an eye on you to see you don’t step out of their boundaries. How then exactly can one hope to form any bond with such people? As such they cease to be normal human beings, their names (unfamiliar and difficult to pronounce as a foreigner don’t also forget) becoming irrelevant.

ヴィトン バッグ 価格