In college, I came across the original diaries of two Fuzhou missionaries that had been gathering dust in our library for more than 100 years. I’ve now lived in China for four years, which seems like long enough to revisit the stories of Mary Allen and Carlos Martin.

Many of us expats view ourselves as arbiters of cross-cultural exchanges and vanguards of Chinese knowledge unto the Western world. We’ve learned chengyu, written papers, blogged, photographed, dated Chinese people, opened bars, been screwed out of our money on multiple occasions, chalked up so, so much to “learning experiences.” But for a real look at how deep the rabbit hole goes, look before 1978, and especially before 1949. The absurdity of living a cross-/multicultural life in China is like a rock swept under rising waters; now, we only see the tip of it.

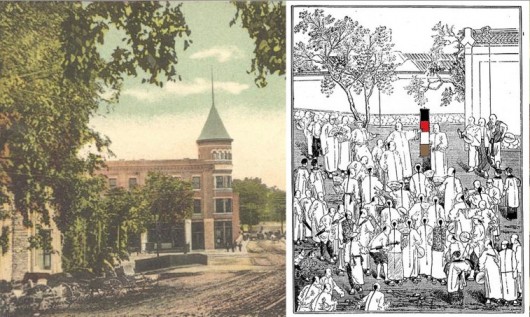

In August 1859, Mary Allen (20) and Carlos Martin (24) married at an Episcopal Church in rural Vermont. Within two months, the town waved its handkerchiefs as the young couple set sail for Fuzhou. After several months of acute seasickness and dolphin-spotting, the Martins were greeted by a band of Protestant missionaries that had rooted in Fuzhou a decade earlier. The Martins settled in; Carl proselytized while Mary bore children. They became members of the community, even befriending Chinese. Then, on January 17, 1864, the town stormed their cottage, demanding blood.

It’s easy to forget in this modern age of Foreign Babes in Beijing and Shanghai Calling, but China once experienced exhilarating schadenfreude in regards to the outside world (literally 国外), and outsiders who came to China lived a life of both privilege and perdition beyond what we now witness in Xintiandi and Sanlitun. Indeed, Mary Martin returned to Vermont after five years in Fuzhou having lost both her husband and infant son.

The Martins were devoted and enthusiastic offspring of the Protestant intellectual movement of the mid-19th century, wherein a middle-class self-evaluation proffered that overseas proselytizing was an undertaking of the highest moral caliber. Once in China, most of these missionaries realized that giving soapbox sermons in the broken local dialect was as effective as having stayed in Vermont. Nonetheless, they set up rice kitchens, orphanages, and hospitals. Slowly, the conversions came.

Still, great barriers rose to oppose them. The Opium Wars had made Chinese feel like second-class citizens in their own land, and paternalistic Confucianism remained ensconced in the aristocracy, as the privileged and influential were the least likely to change their beliefs. The threat posed by the “outside world,” in particular in the form of religion, was a sharp jab to the intellectual and aristocratic classes. “Protecting” and “defending” tradition were (and often still are) conflated with targeting and marginalizing anything foreign.

In the widely read Pixie Jishi (“A record of facts to ward off heterodoxy,” 闢邪紀事), written by an anonymous “Most Heartbroken Man in the World” (in reference to the Opium Wars) in 1861, the author indulges Chinese suspicions of Christians as sexual perverts and churches as loci of orgies. He writes:

During the first three months of life the anuses of all [Christian] infants – male and female – are plugged up with a small hollow tube…It causes the anus to dilate so that upon growing up sodomy will be facilitated. At the junction of each spring and summer boys procure the menstrual discharge of women and, smearing it on their faces, go into Christian churches to worship. They call this ‘cleansing one’s face before paying one’s respects to the holy one, and regard it as one of the most venerative rituals by which the Lord can be worshiped. Fathers and sons, elder and younger brothers, behave licentiously with one another, calling it ‘the joining of the vital forces.’ … Hard as it may be to believe, some of our Chinese people also follow their religion. Are they not really worse than beasts?

Simmering suspicion – and certainly superstition – would have contributed to the gathering of a curious crowd outside the new church in East Fuzhou on January 17, 1864. Carl Martin and his fellow Chinese preacher Xu Yangmei had been preparing the new congregation house for months. As Christians, both Chinese and foreign, shuffled into the new building, unassociated onlookers pushed in as well. They played with the wall ornaments and hung around in the pulpit. When asked to leave, they grew indignant and suspicious. Some face must have been lost in the exchange. A few left and came back with a larger crowd, and actions occurred that today would be front-page news on The New York Times.

Xu Yangmei’s wife and daughters were beaten and raped in the new church, along with other Chinese Christians. Either the foreign members had escaped or were not put on record as having been assaulted at that time; Mary, Carl, and their two sons hurried home and collected their items, literally chased out the back door and into the woods by the mob. They escaped.

The idea of a “harmonious society” – in this case, glossing over punishments and repayments for the sake of maintaining family face and community stability – is by no means the handicapped child of China’s communist regime. The idea arguably originates in Confucian texts, and was certainly pertinent in Fuzhou at the time. The local officials demanded that the lead rioters and rapists apologize to Xu Yangmei, which they did. Face for face, and the incident fell by the wayside.

Carl and his newborn son died of cholera later that year.

Allegedly – I have never gone – the church still remains in East Fuzhou, tended by a direct descendent of Xu Yangmei. One of Carl and Mary’s direct descendants sought him out in the 1990s and was warmly received in that very church.

Paul French once said in an interview, “The laowai experience is a collective one. Everyone needs to stop thinking of their own stories as special.” Looking back on this incident in Fuzhou in 1864, I can’t agree more. And the more I discover incidents such as this, the more I want to shut up about my own experiences. There’s such a rich history that we may all benefit from giving our predecessors a longer listen.

Hannah Lincoln currently lives in Beijing. Her previous pieces for BJC include this airplane story about false assumptions, misunderstanding, and forgiveness.

“The laowai experience is a collective one. Everyone needs to stop thinking of their own stories as special.”

I have lived in China now for 3 1/2 years and sometimes I think, “why haven’t I written a book in that time?” This is why. My experience is nothing special, especially considering what people before me experienced. Life here is surprisingly easy once you get used to it, and then it is rather bland.

Really fascinating read. I enjoyed this so much. Thank you for sharing.

Its not only Laowai but all of us in South East Asia. When you read the history of Asia and what they have been through, every day of peace is a triumph and something to celebrate. Something I have been trying to impart to my children. Nothing is too difficult. Their sufferings or misfortune are incomparable.