Our friends at Beijing Today swing by now and then to introduce art and culture in the city.

It’s hard to imagine that the Tibetan inspired art of Wang Yiguang is the work of a man who grew up on the North China Plain. But Tibet’s vigorous yaks, winding railways and cheerful girls have been the subject of Wang’s creations since he first set foot on the magical plateau in 2002.

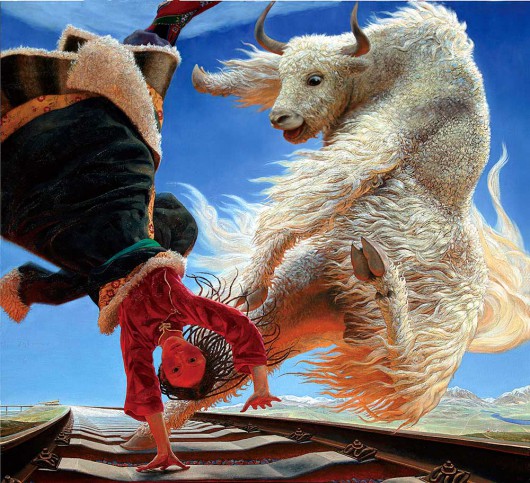

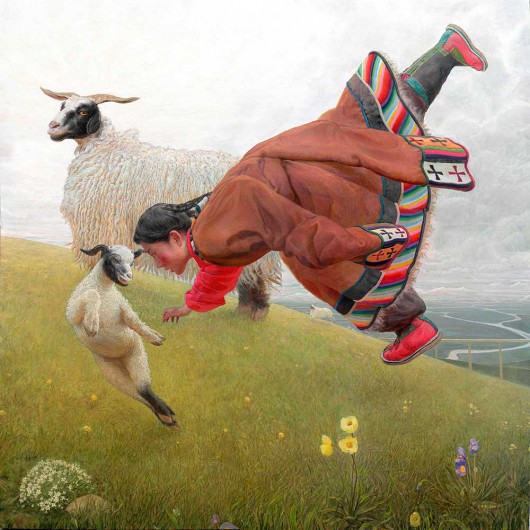

Unlike his Tibet-obsessed peers who focus on the scenery of the Tanggula Mountains and highland prairies, Wang expresses his love for the plateau through super-realist images of flying animals and Tibetans living in a dreamy and harmonious environment.

“I believe in animism and have always tried to find an appropriate way to express it through the interaction between humans and nature,” Wang says. “But the way escaped me until I came to Tibet.”

Born in 1962 in Linyi, Shandong province, Wang grew up with two artistic brothers and started to paint in middle school. When the Cultural Revolution ended and education resumed in 1977, Wang sat China’s first college entrance exam and was admitted to a local art school. He was assigned to work as an art teacher in Shandong province in 1980.

“To be honest, the reason I chose art as my major was because I just wanted to stay in the city. But the more I painted, the more I became fascinated with the art,” Wang says. After graduating from the Central Academy of Fine Arts with a master’s degree in oil painting in 1988, Wang became a graphic designer at the China Railway Construction Corporation.

The majority of Wang’s earlier works were realist paintings that displayed the daily life of villagers prior to the 1990s. But slowly, his work began to morph into neo-realism that combined the power of reality and the romance of imagination. The shift became obvious after he participated in the construction of Qinghai-Tibet Railway in 1992.

In the Fragrance of Kelsang Flowers, Wang depicts a local girl opening her arms and flying into the sky over a sea of highland flowers. The view of the yak’s back makes it seem the carefree girl is sharing her happiness with the creature.

The combination of Tibetan girls and yaks appear in many of Wang’s other works such as After Rian, painted in 2004, and Silent Communication, painted in 2014. Wang is obsessed with the poetic comparison between the Tibetan girls and the yaks, creatures with powerful energy and life force.

“The first time I went to the Tibetan Plateau I fainted due to altitude sickness and oxygen deficiency. The only thing I could do during my first couple days was lie on the grass and gasp for air,” Wang says. “But local kids and yaks could play so freely and happily around me. They were like the Flying Apsaras of the Duhuang Frescoes. That physical reaction let me admire the power of life on the Tibetan Plateau.”

Construction workers on the Qinghai-Tibet Railway are also an important theme in Wang’s work. In Full Moon Over Tanggula, painted in 2005, Wang captures the conditions of railway workers at the foot of snowcapped mountains. The glow of sunset and dancing locals offer a warm and cheerful sense.

“The Qinghai-Tibet Railway, construction workers and daily life on the plateau are the ore of my art. Strong artistic language can only come from the combination of the right artistic approach and the ability to capture life’s details,” Wang says.

Check out more paintings over at Wang Yiguang’s gallery.

This post originally appeared in Beijing Today.

Working link: http://www.wangyidong.com/wangyiguang/shouye.html

Thanks, appended.

Hers a good idea. If BEIJING CREAM can’t think of anything new, borrow articles from someone else. Brilliant!

Here’s the original article: http://beijingtoday.com.cn/2015/04/capturing-the-energy-of-life-on-the-tibet-plateau/

Fuckwits. Anthony you are a turd.

Our collaboration with Beijing Today is clearly indicated at the top and bottom of this post, and all posts under the tag http://beijingcream.com/tag/beijing-today